13.3.7: Strategies that Support Language Development-Baby Signs and Sign Language

- Page ID

- 140683

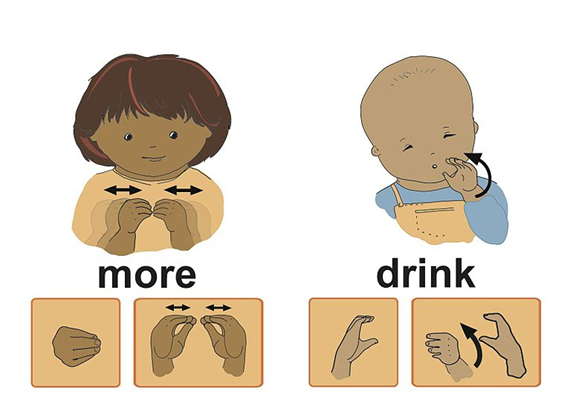

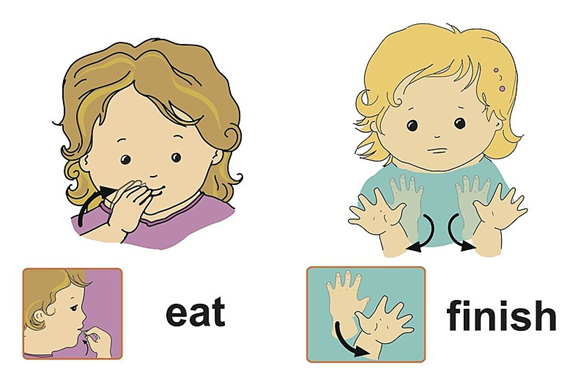

Baby Signs and Sign Language

Baby signs are gestures created to provide an early way for caregivers to communicate with infants and toddlers and acquire insight and respect for underestimated communicative abilities of children before they can talk (Vallotton, 2008; 2011). The baby signs system is not a full system and is not the same as sign language. Baby signs were created as a means to ease communication as manual communication often precedes spoken language production (Goldin‐Meadow, Goodrich, Sauer & Iverson, 2007). Baby signs are usually used while simultaneously using a spoken language and do not mark each word spoken in a sentence. For example, if a caregiver asks an infant, “Do you want more?”, the baby sign for ‘more’ will be used when the spoken word ‘more’ is pronounced.

In comparison to baby signs, sign languages are fully-fledged language systems naturally created by Deaf individuals. As misconceptions about sign languages continue to persist, there are a few facts to know: [2]

- Sign languages are complex language systems with similar linguistic properties as spoken languages (Sandler, 2017; Woll, 2013).

- Most countries have their own sign language (Jepsen, De Clerck, Lutalo-Kiingi & McGregor, 2015), such American Sign Language in the U.S., Lengua de Señas Mexicana in Mexico and Nederlandse Gebarentaal, the primary sign language used in the Netherlands.

- Infants and toddlers learning a signed language as a native language show acquisition patterns and reach milestones similar to children learning a spoken language (Caselli, Lieberman & Pyers, 2020; Lillo-Martin & Henner, 2021; MacDonald et al., 2018).

- Similar neural systems support the processing of both signed and spoken languages (Corina & McBurney, 2001; MacSweeney, Capek, Campbell & Woll, 2008).

After early investigations reported that very young children of Deaf parents often attained early language milestones in sign language at younger ages than children learning a spoken language (Bellugi, & Klima, 1982; Bonvillian, Orlansky & Novack, 1983; McIntire, 1977), other investigators began to study the learning of signs or symbolic gestures by the young hearing children of hearing parents (Acredolo & Goodwyn, 1996; Goodwyn & Acredolo, 1993, 1998). In this research, those infants who were taught a collection of “baby signs” typically acquired the signs faster than speech-trained infants acquired a collection of spoken target words. The investigators attributed the children’s slower acquisition of spoken words to the difficulties and complexities involved in spoken language production early in a child’s development. In other words, a child’s physical ability to produce speech or control the muscles needed for recognizable speech seems to lag behind the child’s physical ability to control the arm and hand movements needed to produce recognizable signs. The children in the sign-trained group showed a long-term advantage on a number of language development measures throughout early childhood, as well as higher school-age IQ scores (Acredolo, Goodwyn, & Abrams, 2002; Goodwyn, Acredolo, & Brown, 2000). These findings indicate that early signing or symbolic gesturing does not hamper verbal development and may, in fact, enhance it. [3]

In another investigation, forty infants were followed from the age of eight months to twenty months where half of the mothers modeled signs or gestures for a limited number of target set signs, whereas the remaining half of the mothers focused on spoken language input (Kirk, Howlett, Pine & Fletcher, 2013). The mothers in the sign/gesture-input conditions became more sensitive to their infants’ nonverbal cues than the mothers in the speech-only condition. Numerous studies have shown that use of baby signs is related to more responsiveness from caregivers and helps infants and caregivers to be more insync with each other when interacting (Góngora & Farkas, 2009; Norman & Byrne, 2021; Olson & Masur, 2013; Paul et al., 2019; Vallotton, 2009; 2012; Zammit & Atkinson, 2017). This increased sensitivity to infants’ nonverbal cues may be an important benefit of sign input as such sensitivity may contribute to closer caregiver-infant bonding. [3]

In an attempt to explain the positive outcomes associated with baby-signing in their research, Goodwyn and Acredolo suggested that the children’s symbolic gestures or signs may have elicited more spoken language input from the children’s parents as well as indicated to the parents the specific topics in which the children were interested in. There are, however, other possible interpretations. One is that combining sign and spoken language input may facilitate the vocal production of typically developing babies as it does for many children with Down syndrome (Özçalişkan et al., 2016) or autism (Özçalişkan et al., 2017). A second possibility is that because “baby-signing” typically involves caregivers producing signs for only the key words in their utterances, this combining of signs and spoken language may help infants segment the speech stream by making the signed words more prominent, thus facilitating their acquisition (Mueller & Acosta, 2015). [3]

Along with the claim of potentially fostering more rapid spoken language development, the early use of signs also has been associated with fewer and less severe temper tantrums in infancy and early childhood (Acredolo et al., 2002). Additional support for this claim of improved social behavior is seen in a study of hearing infants who were taught manual signs early in their lives. Once these infants acquired minimal functional sign skills, their incidence of crying and whining decreased substantially (Thompson et al., 2007). [3]

Caregivers can easily learn basic signs and use them with infants and toddlers. Using baby signs per se is not necessary. Baby signs are based on signed languages and often require unnecessary financial purchases. Baby signs are sometimes modified to be easier to manually produce for young children, but young children natively acquire sign languages and naturally produce signs that caregivers can understand even if they are not exact replicates of the adults’. Two free resources to learn signs are Lifeprint created by Dr. Bill Vicar and the ASL Sign Bank.

[1] Image from Michael D. Fetters is licensed under CC by SA 3.0

[2] Corina et al., (2013). Cross-linguistic differences in the neural representation of human language: Evidence from users of signed languages. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 587. CC by 3.0

[3] Bonvillian et al., (2020). Simplified signs: A manual sign-communication system for special populations. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers. CC by 4.0

[4] Image from Michael D. Fetters is licensed under CC by SA 3.0

[5] Image from Michael D. Fetters is licensed under CC by SA 3.0