13.3.9: Strategies that Support Language Development-Dialogic Reading

- Page ID

- 140685

Dialogic Reading

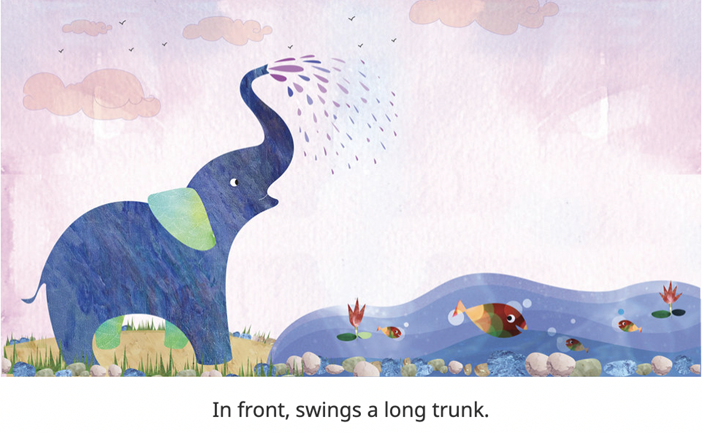

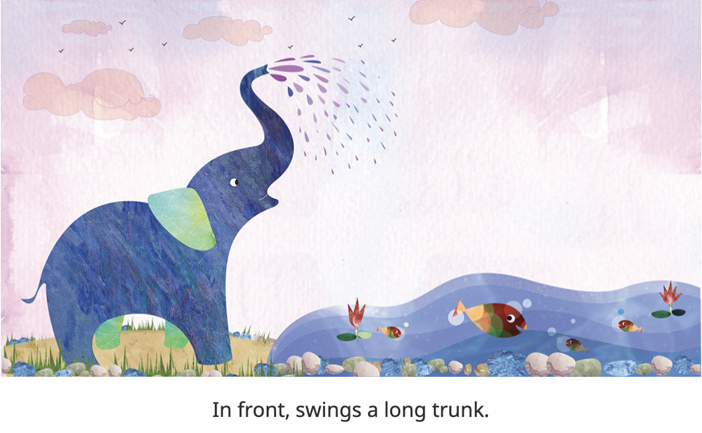

Imagine you are sitting down to read a book with a toddler. You open the book and Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows what is on the first page. Take a moment to look at the page in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) and consider how you would read this page with a toddler.

For many of us, we read books with children by focusing on the text. Reading the words on the pages is a great start, but there can be so much more to discuss! Variation in how books are read and discussed has been found to be important. Ninio (1980) examined interactions between Israeli caregivers and infants between 17 and 22 months of age. Caregivers tended to use one of three interactional routines, asking one of two types of questions “What’s that?,” “Where’s that?,” or simply naming objects. A large study of the reading approaches of 126 caregivers found variability in how they read to children at age 7 and 24 months (Britto, Brooks-Gunn & Griffin, 2006). Caregiver reading style was related to language growth, with children showing greater language growth when they were encouraged to participate in the reading and supported in their understanding; however, this reading style was found in only 30 of the 126 caregivers. [2]

One of the most common methods to improve caregivers’ reading with young children is dialogic reading as it is not commonly implemented when caregivers read with infants and toddlers (Huebner & Meltzoff, 2005). To encourage caregivers to see that reading should be about more than just the words on pages, reading with infants and toddlers is best perceived as an interaction between the caregiver, the child and the book. Perceiving book reading as more of an interaction is oftentimes referred to as dialogic reading. Dialogic reading uses techniques that encourage the caregiver to be responsive to the child with conversations that follow the child’s interest and lead. Dialogic reading typically involves recasts, expansions, and open-ended questions, all of which have been shown to have a positive impact on a child's language development (Baker & Nelson, 1984; Cleave et al., 2015; Farrar, 1990; Girolametto & Weitzman, 2002; Huttenlocher et al., 2010; Nelson, 1977). A meta-analysis of dialogic reading found that it loses its value with the older children (Mol, Bus, De Jong & Smeets, 2008). It may be that the method is best suited to book reading with infants, toddlers, and younger preschool children. [2] [3]

One reason dialogic reading is so beneficial for children’s language development is because it involves quality language-boosting practices. For example, the child-directed speech delivered during interactive shared book reading contains higher levels of syntactic and lexical diversity than the speech children are exposed to during play-based activities (Cameron-Faulkner & Noble, 2013; Demir‐Lira, Applebaum, Goldin‐Meadow & Levine, 2019; Noble et al., 2018; Salo, Rowe, Leech & Cabrera, 2016), and high levels of syntactic and lexical diversity in speech directed to children are linked to higher levels of syntactic and lexical diversity in children's speech (Huttenlocher et al., 2002). Interactive shared book reading has also been shown to foster higher levels of joint attention, responsiveness, and contingent talk, all of which have been shown to support language development (Carpenter et al., 1998; Farrant & Zubrick, 2013; McGillion, Pine, Herbert & Matthews, 2017; Tomasello & Farrar, 1986). It also encourages the caregiver to use additional language-boosting practices, which have all been shown to support children's language development, including expanding, recasting, and asking open-ended questions (Baker & Nelson, 1984; Cleave et al., 2015; Girolametto & Weitzman, 2002; Huttenlocher et al., 2010). []

Many studies that have trained caregivers in dialogic reading strategies report positive gains in young children’s language outcomes (Chacko, Fabiano, Doctoroff & Fortson, 2018; Grolig, Cohrdes, Tiffin-Richards & Schroeder, 2020; Kim & Riley, 2021; Lonigan et al., 1999; Opel, Ameer & Aboud, 2009; Purpura, Napoli, Wehrspann & Gold, 2017; Simsek & Erdogan, 2015; Towson, Gallagher, & Bingham, 2016; Valdez-Menchaca & Whitehurst, 1992). For example, Valdez-Menchaca and Whitehurst (1992) trained teachers to read using a dialogic reading style that involved asking more open-ended questions and responding to children's attempts to answer these questions with low-income Mexican toddlers. Children who received the dialogic reading intervention scored significantly higher on measures of both expressive and receptive language than children in the control group. [3]

Many studies have found that asking basic comprehension questions during shared reading increases the effects on oral language skills in comparison to reading story books aloud without asking questions (Flack, Field & Horst, 2018; Wasik, Hindman & Snell, 2016). Asking such literal comprehension questions both serves to attain joint attention and to establish a fundamental understanding of concepts and events. Discussing the meanings of new words in the context of the story and in other contexts facilitates a deeper word understanding (Coyne et al., 2009). [5]

By implementing the PEER sequence, the caregiver: [3]

- prompts the child to say something about the book,

- evaluates the child's response,

- expands the child's response, and

- repeats the prompt to help the child learn from the expansion.

A fundamental element of dialogic reading is the use of prompts to begin the PEER sequence while reading with a child. The acronym CROWD stands for five recommended prompts:[3] [6]

- Completions

- Example: “Five little monkeys jumping on the _____”. The child fills in “bed” to participate in completing the thought.

- Recalls

- Example: What happens after the wolf huffs and puffs? The child recalls the story and puts that into their own words.

- Open questions

- Example: “Tell me what is happening in this picture.” The child practices putting their own thoughts into words.

- Wh-questions

- Example: What is that? Why is that happening? At many different levels children can put their thoughts into words.

- Distancing questions

- Example: What happened when we made your birthday cake? Children remember past events and relate them to the present and future.

Let’s take another look at the page from a children’s book presented earlier. Imagine creating an interaction with the child about this page using the PEER and/or CROWD dialogic reading strategies. After imagining what you might say using the dialogic reading strategies, reflect on how the quantity and quality of your language was impacted.

[1] Haathibhai by Pratham Books is licensed under CC by 4.0

[2] Dickinson et al., (2012). How reading books fosters language development around the world. Child Development Research. CC by 3.0

[3] Noble et al., (2020). The impact of interactive shared book reading on children's language skills: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 63(6), 1878-1897. CC by 4.0

[4] Image from Head Start ECLKC is in the public domain.

[5] Grolig (2020). Shared storybook reading and oral language development: A bioecological perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1818. CC by 4.0

[6] “Using Mariposa, Mariposa (Butterfly, Butterfly) to promote dialogic reading: A powerful way to encourage language development in one or more languages” from Head Start ECLKC is in the public domain.