14.2: Defining Multilingualism

- Page ID

- 140759

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)What is Multilingualism?

What does it mean to be multilingual? Across educational and research fields, a number of different terms and definitions have been used to describe children who are multilingual. The term multilingual may encompass or overlap substantially with other terms frequently used, such as ‘bilingual’, ‘dual language learner’, ‘English language learner’ and ‘children who speak a language other than English’. For the purpose of this section, the term multilingual refers to children who are learning two (or more) languages at the same time, or learning an additional language while continuing to develop their native language(s). [1]

Multilingualism is a complex construct that has been redefined over the past several decades. Scholars once defined multilinguals exclusively as a small group of speakers who were perfectly “balanced” in their languages (Lambert, Havelka, Gardner, 1959). The definition of multilingualism has since expanded to include individuals with varying degrees of proficiency and different language experiences. An individual’s multilingual status is not a trait that can be directly measured一multilingualism cannot be determined in the same way as someone’s height, for example. When measuring multilingualism, researchers often rely on a combination of factors, such as language proficiency and amount of exposure, to determine an individual’s multilingual status (Anderson, Mak, Keyvani Chahi & Bialystok, 2018; Li, Sepanski & Zhao, 2006, 2014; Marian, Blumenfeld & Kaushanskaya, 2007; Marian & Hayakawa, 2020). [1]

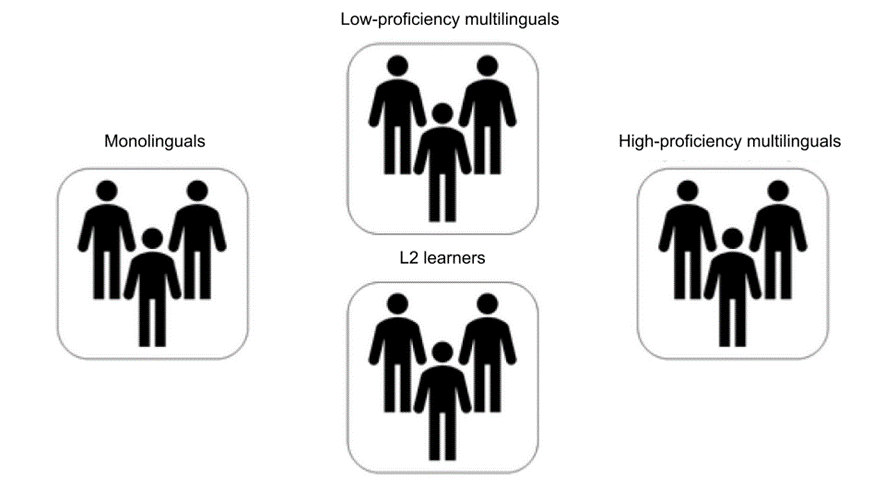

In order to account for the full spectrum of multilinguals’ experiences and language abilities, some scholars have proposed that multilingualism should be viewed as a continuous variable (Baum & Titone, 2014; de Bruin, 2019; Kaushanskaya & Prior, 2015; Marian & Hayakawa, 2020; Takahesu Tabori, Mech & Atagi, 2018). Under such an approach, the continuum of being multilingual would span the range from completely monolingual (i.e., never having any exposure to a second language) to fully proficient multilingual (i.e., “balanced” across languages).Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows a visual representation of a continuous model of multilingualism. Other models of multilingualism may even combine both categorical and continuous models (Kremin & Byers-Heinlein, 2021). Clearly, being multilingual is much more complex than simply learning or knowing two or more languages. [3]

Each multilingual child’s language learning experience is unique: children differ in terms of the specific languages they are learning, when they start learning each, and how they experience them. Contexts for multilingualism may be very different across families, child care programs, communities, and cultures (Rowe & Weisleder, 2020). Taking this diversity into account is key to understanding early multilingual development. As a result, each multilingual child will have their own developmental path (de Bruin, 2019)一there are nearly as many ways to grow up multilingual as there are multilingual children! [6]

Despite the diversity, a common factor across multilingual development is the crucial role of the quantity and quality of exposure infants and toddlers receive in their different languages (Marchman, Fernald & Hurtado, 2010; Ramírez‐Esparza, García‐Sierra & Kuhl, 2017). For example, we would not expect a child to learn a language they only hear for 5 minutes per day (low quantity) or to learn a language from 5 hours a day of isolated vocabulary words recited from an audiotape (low quality). It is difficult to know exactly what combination of quantity and quality is required, but some studies estimate that children need a minimum of 10% to 25% of overall exposure in a language to achieve fluency in it, which will only occur if their language experience is rich and varied (Place & Hoff, 2011). If children do not receive sufficient high-quality multilingual exposure, they are unlikely to become proficient in all of their languages. [7]

[1] US Department of Health and Human Services. (2017). Policy statement on supporting the development of children who are dual language learners in early childhood programs is in the public domain.

[2] Image from Saradhi Photography on Unsplash.

[3] Kremin & Byers-Heinlein (2021). Why not both? Rethinking categorical and continuous approaches to bilingualism. International Journal of Bilingualism, 25(6), 1560-1575. CC by 4.0

[4] Image adapted from Kremin & Byers-Heinlein (2021). Why not both? Rethinking categorical and continuous approaches to bilingualism. International Journal of Bilingualism, 25(6), 1560-1575. CC by 4.0

[5] Image from Kremin & Byers-Heinlein (2021). Why not both? Rethinking categorical and continuous approaches to bilingualism. International Journal of Bilingualism, 25(6), 1560-1575. CC by 4.0

[6] Fibla et al., (2021 preprint). Bilingual language development in infancy: What can we do to support bilingual families? CC by 4.0

[7] Fibla et al., (2021 preprint). Bilingual language development in infancy: What can we do to support bilingual families? CC by 4.0