In an insightful and popular study of capital accumulation, from both a historical and contemporary perspective, Thomas Piketty draws our attention to the enormous inequality in the distribution of wealth and explores what the future may hold in his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

The distribution of wealth is universally more unequal than the distribution of incomes or earnings. Gini coefficients in the neighbourhood of 0.8 are commonplace in developed economies. In terms of shares of the wealth pie, such a magnitude may imply that the top 1% of wealth holders own more than one third of all of an economy's wealth, that the top decile may own two-thirds of all wealth, and that the remaining one third is held by the 'bottom 90%'. And within this bottom 90%, virtually all of the remaining wealth is held by the 40% of the population below the top decile, leaving only a few percent of all wealth to the bottom 50% of the population.

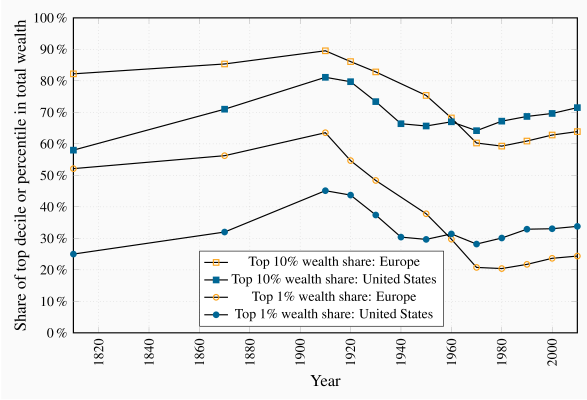

While such an unequal holding pattern may appear shockingly unjust, Piketty informs us that current wealth inequality is not as great in most economies as it was about 1900. Figure 13.5 (Piketty 10.6) above is borrowed from his web site. Wealth was more unequally distributed in Old World Europe than New World America a century ago, but this relativity has since been reversed. A great transformation in the wealth holding pattern of societies in the twentieth century took the form of the emergence of a 'patrimonial middle class', by which he means the emergence of substantial wealth holdings on the part of that 40% of the population below the top decile. This development is noteworthy, but Piketty warns that the top percentiles of the wealth distribution may be on their way to controlling a share of all wealth close to their share in the early years of the twentieth century. He illustrates that two elements are critical to this prediction; first is the rate of growth in the economy relative to the return on capital, the second is inheritances.

To illustrate: Imagine an economy with very low growth, and where the owners of capital obtain an annual return of say 5%. If the owners merely maintain their capital intact and consume the remainder of this 5%, then the pattern of wealth holding will continue to be stable. However, if the holders of wealth can reinvest from their return an amount more than is necessary to replace depreciation then their wealth will grow. And if labour income in this economy is almost static on account of low overall growth, then wealth holders will secure a larger share of the economic pie. In contrast, if economic growth is significant, then labour income may grow in line with income from capital and inequality may remain stable. This summarizes Piketty's famous (r–g) law – inequality depends upon the difference between the return on wealth and the growth rate of the economy. This potential for an ever-expanding degree of inequality is magnified when the stock of capital in the economy is large.

Consider now the role of inheritances. That is to say, do individuals leave large or small inheritances when they die, and how concentrated are such inheritances? If individual wealth accumulation patterns are generated by a desire to save for retirement and old age – during which time individuals decumulate by spending their assets – such motivation should result in small bequests being left to following generations. In contrast, if individuals who are in a position to do so save and accumulate, not just for their old age, but because they have dynastic preferences, or if they take pleasure simply from the ownership of wealth, or even if they are very cautious about running down their wealth in their old age, then we should see substantial inheritances passed on to the sons and daughters of these individuals, thereby perpetuating, and perhaps exacerbating, the inequality of wealth holding in the economy.

Piketty shows that in fact individuals who save substantial amounts tend to leave large bequests; that is they do not save purely for life-cycle motives. In modern economies the annual amount of bequests and gifts from parents to children falls in the range of 10% to 15% of annual GDP. This may grow in future decades, and since wealth is highly concentrated, these bequests in turn are concentrated among a small number of the following generation – inequality is transmitted from one generation to the next.

As a final observation, if we consider the distribution of income and wealth together, particularly at the very top end, we can see readily that a growing concentration of income among the top 1% should ultimately translate itself into greater wealth inequality. This is because top earners can save more easily than lower earners. To compound matters, if individuals who inherit wealth also tend to inherit more human capital from their parents than others, the concentration of income and wealth may become yet stronger.

The study of distributional issues in economics has probably received too little attention in the modern era. Yet it is vitally important both in terms of the well-being of the individuals who constitute an economy and in terms of adherence to social norms. Given that utility declines with additions to income and wealth, transfers from those at the top to those at the bottom have the potential to increase total utility in the economy. Furthermore, an economy in which justice is seen to prevail—in the form of avoiding excessive inequality—is more likely to achieve a higher degree of social coherence than one where inequality is large.