24.4: Getting Different Reactions Throughout the Course

- Page ID

- 88309

Peer Review and Self-Evaluation

Another strategy is to create benchmarks for yourself and take time each week to see how you are doing. For example, if you set a goal to answer a certain number of discussion threads in a particular forum, keep track of how many replies you submit, and make adjustments. If you want to return all students’ written assignments in a certain amount of time, note how many you were able to complete within your self-imposed deadline. This will help you create more realistic expectations for yourself for future assignments.

Online Suggestion Box

Online suggestion boxes are unstructured activities that capture voluntary comments at irregular intervals throughout an entire term. You can use email or a threaded discussion forum for this activity. If you use a discussion forum, let students know if their contributions will be graded or non-graded. In some Learning Management System (LMS) solutions, you can allow anonymous comments. Tell students that you will allow anonymous comments as long as they remain constructive. You could make it a portion of a participation grade to enter a certain number of suggestions throughout the term. To focus their comments, give a list of items about which you want feedback, such as amount of respect shown to students and their ideas, variety of avenues to reach learning objectives, amount of feedback provided, relevance of coursework to the world, communication practices, or willingness to make changes based on student feedback. If it is a hybrid or face-to-face course, bring the suggestions back to the classroom and announce them in front of the class, so that students know their ideas have been heard and are being addressed.

One-Minute Threads

Normally used as a classroom assessment technique (CAT), one-minute papers ask students to write three things in one minute:

- what they felt was clear, helpful, or most meaningful from a course reading, lecture, or classroom meeting;

- what they felt was “muddy,” unclear, or least meaningful from a course reading, lecture, or classroom meeting; and

- any additional comments.

With only a minute to write these three things, students provide short, concentrated answers rather than lengthy passages. This makes it easier to see what works and what does not. For example, a biology student might write “clear—basic cell structure,” “unclear—4 phases of mitosis / cell division,” and “comment—please show more animations and pictures … they help.” This process can be anonymous or not, depending on how you plan to use the results. Angelo and Cross (1993) explain the concept of the one-minute paper in their book about CATs, while Chizmar & Ostrosky (1998) cover its benefits in detail.

In the classroom setting, the instructor collects all of the papers and looks for patterns, or areas that are clear or unclear to several students. With this information, they can address problem areas at the beginning of the next class meeting before moving to new material. To respond to less common comments, the instructor may opt to post additional resources, such as journal articles or links to websites that cover a problem area in more depth or from another perspective. Instead of covering the less common problems in class, the instructor has the option of providing more materials related to specific areas, and being open to additional questions.

I began asking students to go through the one-minute paper exercise in an online discussion forum when several international students asked for more time to think about what they did not understand. Writing their thoughts right at the end of the class meeting did not give them a chance to digest what we had done. They wanted to go over their notes from the face-to-face class, to translate any unfamiliar terms and ideas, and sometimes even to discuss the concepts in a small group. By going online, they could have more time to process their thoughts and still give me feedback before the next class meeting.

This new practice turned out to benefit everyone. (See the section on Universal Design for Learning in Chapter 11, Accessibility and Universal Design.) Instead of waiting until the next class period to respond to student needs, I could use the discussion forum to answer each student’s question fairly quickly. After only two weeks, something amazing happened. Without prompting, students began answering each other’s questions before I had a chance to reply. An online community had formed around a classroom assessment technique that is traditionally not such an open process, being facilitated by the instructor alone. To note the difference, I have started calling this exercise “one-minute threads,” encouraging students to help each other from the beginning.

Note

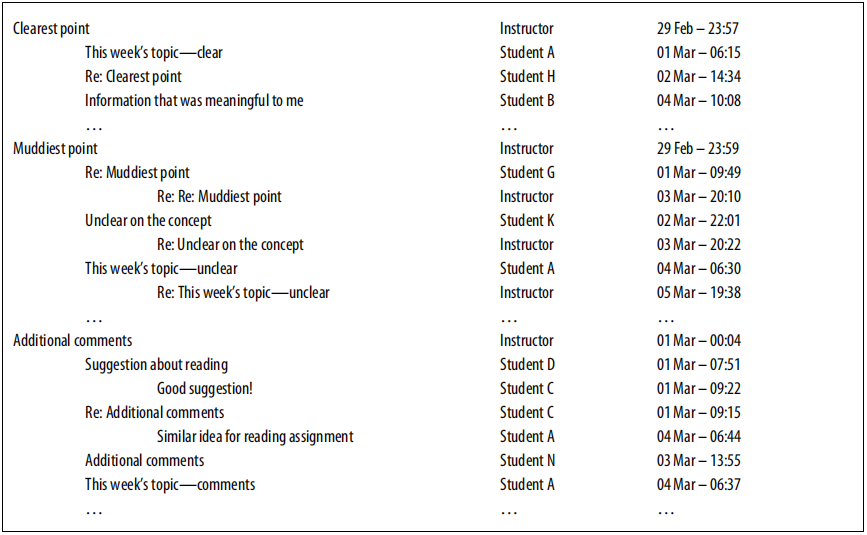

When creating the settings for a “one-minute threads” discussion forum, do not allow students to post their own original threads or discussion topics. Otherwise, the threads will be hard to sort, since they may not have clear subject lines, and will be added in a fairly random order. Instead, ask them to reply to three specific questions (clearest point, muddiest point, and additional comments). This organizes the responses for you. If your LMS or other discussion forum engine does not allow this, write clear instructions for giving the specific responses you are trying to elicit.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows an example discussion forum, demonstrating how requiring students to reply to the instructor’s threads will organize the information for you. For the muddiest point, you can see that the instructor has replied to each student individually. Under “Additional comments,” you can see that some students have responded to each other.

Poling

There are various online polling tools that allow you to get small amounts of feedback in a short time. Some of these polling tools are built into LMS solutions, such as Moodle’s Choice module, allowing instructors to ask single questions related to the material, a course reading, or instructional practice.

Focus Group

Ask a small group of students to join you once a month, either physically (e.g., office hours) or virtually (e.g., chat, discussion forum). These could be the same students for the entire term or a new group of students each time. During your meeting, ask them specific questions to determine information about learning objectives, resources and how they are organized, online activities, assessment strategies, amount of feedback, or other aspects of your teaching that you want to improve.

Note

The students are more likely to respond honestly if their comments are anonymous. In this case, you might assign someone from the small group to ask the questions, another to keep track of time, and a third person to take notes that they post as a group or send by email. Most LMS chat tools do not allow students to block the instructor from seeing the archive, so you may have to disable the archive for that chat, if possible. The note taker can copy and paste the entire chat into a word processing document for summarizing, editing, and removing student’s names. Other options include telling the students to use a free Instant Messenger (IM) service to hold the chat session outside the online environment for the course.

Mid-Semester Evaluation Survey

If you would prefer a larger scale approach than a focus group, try a mid-semester survey. I have used different tools, two of which allowed anonymous student responses, but there are several more. Those that I have used are called the Free Assessment Summary Tool (FAST—http://www.getfast.ca) and survey tools within LMS solutions, such as Blackboard’s Survey Manager, WebCT’s Quiz and Survey module, and Moodle’s Survey module or Questionnaire module.

While it is not perfect, I like FAST for several reasons:

- It is free.

- Anyone can use it to create surveys. It does not require that your campus have a LMS.

- Student responses are anonymous. In addition the survey is conducted in a password- protected environment, so you can be reasonably sure no one who is not enrolled in your course is critiquing your work.

- It provides a question database with more than 350 survey questions related to different aspects of teaching effectiveness. These questions are organized into 34 categories such as Assignments, Enthusiasm, Feedback, Instructor Content Knowledge, Learning Environment, and Student/Student Interaction. You can choose questions from the database, or make your own questions, or both.

- Instructors can download the results as a Microsoft Excel file.

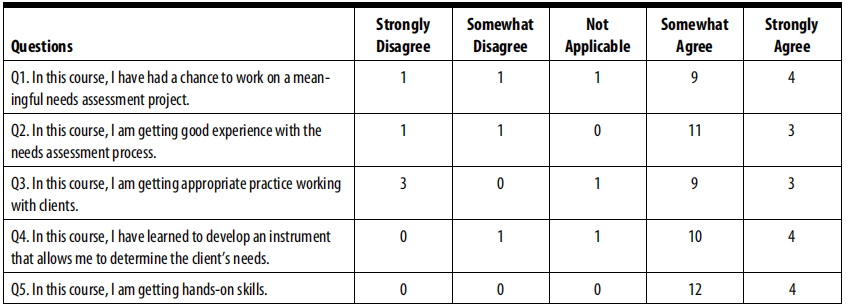

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) contains five items from the anonymous, twenty-question survey I conduct each semester using FAST. The first set of ten questions relate to the student expectations that they define during the first week of the term. The second set of ten questions relate to different elements of teaching effectiveness that I want to improve. Sixteen out of twenty-one graduate students responded.

For my survey, I choose the “Likert Scale & Long Answer” option for each question. That way I can get quantitative data, numbers that quickly tell me what students like or do not like, and qualitative data, written comments that, I hope, will tell me how to improve different parts of my class. Here are some example responses for Question 5, “In this course, I am getting hands-on skills”:

- “I agree that I am getting hands on skills, or that theoretically I am. I think that having a client in the immediate area or available to talk to the students on an ongoing basis would be better than allowing a client to communicate solely by email and at their discretion. A contract drafted by the two parties would be desirable when going forward”.

- “Kevin brings in great examples. I feel that a day of lecture on starting and finishing a needs assessment may be helpful to anchor the learning a bit. I am really working with clients”.

- “Yes, in the sense that I am working on all the steps with my group mates, but I wonder how I would do outside the context of this class …”.

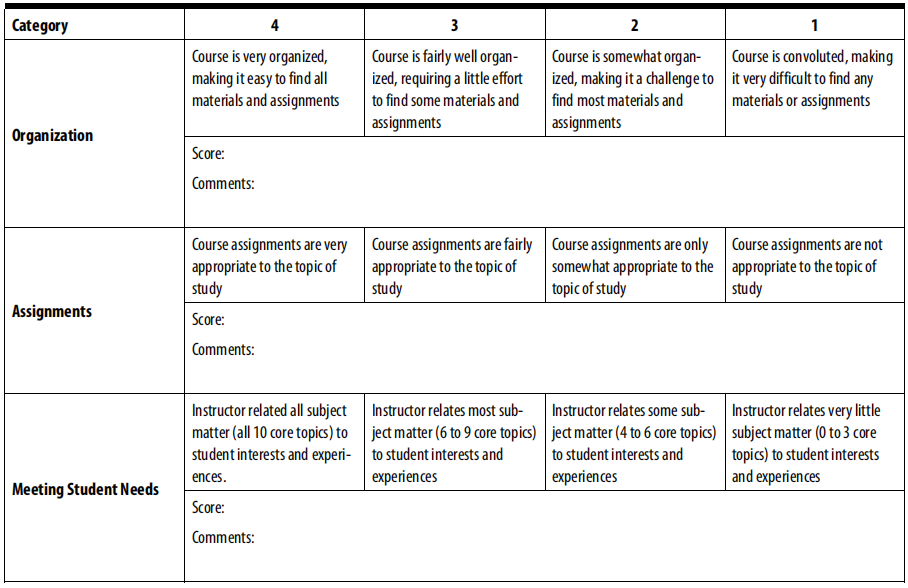

Online Teaching Effectiveness Rubric

If you take the time to create a rubric with your students at the beginning of the semester, then you have to use it some time! This might also be a mid-semester event (in lieu of a survey), or you might ask different teams to complete the rubric at different times. In this way, each student might only complete it once, but you will get feedback once a month or even more frequently. Later I will talk about addressing the students’ feedback, both individually and as an entire class. If you choose to use a rubric, make sure to leave time to explain the concept to the students. Going over the results will take longer than an online survey, but the qualitative data provides much more value than survey results alone.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) contains some example criteria from a rubric that my students and I created together. Notice how the range for evaluating each criterion can be qualitative or quantitative in nature. Also, it is important to provide space for written comments so students can suggest ways to improve.

You do not always have to ask, “How am I doing?” to evaluate online teaching effectiveness. You can also use indirect methods to collect formative feedback. These indirect methods include, but are not limited to, the following.

One-sentence summary

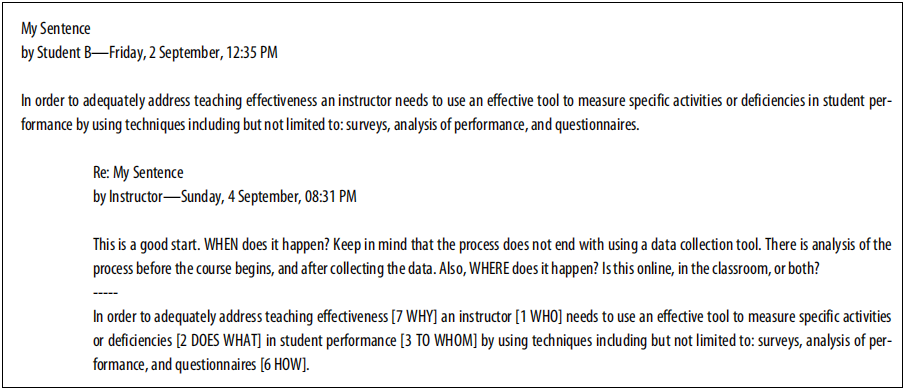

The one-sentence summary is another classroom assessment technique that I adapt to the online environment. Designed to elicit higher level thinking, a one-sentence summary demonstrates whether or not students are able to synthesize a process or concept. Students answer seven questions separately: “Who? Does What? To Whom (or What)? When? Where? How? and Why?” Then they put those answers together into one sentence. Angelo and Cross (1993) also describe this exercise in their book about classroom assessment techniques. Examples I have seen include assigning nursing students to write a one-sentence summary of a mock patient’s case, as nurses are often required to give a quick synopsis about each patient, and asking engineering students to write a summary about fluid dynamics in a given situation.

It is fairly easy to use this technique online. You can set up a discussion forum to collect the student entries. The online environment also makes it fairly easy to engage students in a peer review process and to provide timely feedback.

When looking at the results of the students’ summaries, you can identify areas where large numbers of students did not demonstrate an understanding of the topic or concept. The most common problem area for students revolves around the question “Why?” The instructor’s reply gives suggestions for improvement and shows the student how the instructor interpreted the sentence components.

Student-generated test questions

Ask students to create three to five test questions each. Tell them that you will use a certain number of those questions on the actual test. By doing this, you get the benefit of seeing the course content that the students think is important compared to the content that you think they should focus on. You can make revisions to your presentations to address areas that students did not cover in their questions. If there are enough good student questions you can also use some for test review exercises.

Evaluate online quiz or test results

If you use a learning management system (LMS), an online workbook environment that comes with publisher materials, or other online space that allows online quizzes or tests, then you can use the results to identify problem areas. LMS solutions like Moodle and ANGEL provide tools to perform an item-by-item analysis to evaluate several factors related to individual questions. These factors include item facility, an indicator of the question difficulty for students; standard deviation of student responses on each question; and item discrimination, an indicator of the difference between performance by high-scoring students and low-scoring students.

Even if you can only get simple statistics, such as how the class answered each question overall (e.g., 10 percent picked “A,” 25 percent picked “B,” 65 percent picked “C”), you can use this information to make adjustments. One way to do this is to ask your students to take a pretest or baseline quiz at the beginning of the course, and then compare those results to the actual quiz results. In face-to-face or hybrid course situations, you can use the quiz results to address issues through quiz reviews or changes in your lecture. Dr. Karen Grove from San Francisco State University discusses how to use quiz results to address learning gaps via a student preparation module in the Orientation to College Teaching (http:// oct.sfsu.edu/implementation/studentprep/index.html). If large numbers of the students get a question wrong, the instructor can cover that topic more fully. The instructor can also dispel misconceptions after seeing how many students choose a particular incorrect answer. The instructor can see how many people select each answer. For essay questions, it provides a complete list of all the essays.