9.4: Why is Wealth So Unequal in the U.S.?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 143339

- Ulysses Acevedo

Wealth Inequality

. . . But I couldn't get away

No matter how far I went

Seems like nothing gonna change

Everything still remained the same

Why is it so hard

To make it in America

I try so hard

To make it in America

Why, tell me, tell me

We gotta make a change, in America

Help me somebody

Song: "Why Is It So Hard" (2011) by Charles Bradley (1948 - 2017)

Many of the racial economic inequalities in the U.S. originated with the property and assets accrued by white individuals and institutions through colonization and the theft of native land, and through slavery. The legacy of this unequal wealth has continued in the white families and institutions which have inherited it, the law enforcement systems created to protect it, and the Black and indigenous communities (often violently) deprived of it.

In a powerful impromptu speech during the demonstrations against the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police, Kimberly Jones Powell explains the enduring effect of slavery and ongoing state-sponsored violence on wealth in the Black community:

So, if I play four hundred rounds of Monopoly with you, and I had to play and give you every dime that I made, and then for fifty years every time that I played and if you didn’t like what I did, you got to burn like they did in Tulsa and like they did in Rosewood. How can you win? You can’t win. The game is fixed. So when they say, “Why do you burn down the community? Why burn down your own neighborhood? It’s not ours! We don’t own anything! We don’t own anything! There is… Trevor Noah said it so beautifully last night. There is a social contract that we all have that if you steal or if I steal, then the person who is the authority comes in, and they fix the situation. But that the person this situation is killing us! So the social contract is broken! And if the social contract is broken, why the fuck do I give a shit about burning the fucking Football Hall of Fame or about burning a fucking Target? You broke the contract when you killed us in the street and didn’t give a fuck! You broke the contract when for four hundred years, we played your game and built your wealth! You broke the contract when we built our wealth again on our own, on our bootstraps in Tulsa, and you dropped bombs on us! When we built it in Rosewood and you came in and you slaughtered us! You broke the contract! So fuck your Target! Fuck your Hall of Fame! As far as I’m concerned, they could burn this bitch to the ground. And it still wouldn’t be enough. And they are lucky that what Black people are looking for is equality and not revenge (Jones, 2021, p. 10).

Jones uses a fixed game of Monopoly as an allegory for the U.S. pretending that there is a fair and objective economic system, when really 400 years of slavery and the violent systems that have persisted since (such as Jim Crow, lynchings, racial massacres, and mass incarceration) is the same as cheating every round, and has made the game impossible to win. She points out that the social contract was violently broken so many times and in so many ways, that the 2020 rioting is justified and completely pales in proportion to the violent wealth extraction inflicted on the Black community over centuries.

While much of the racial and ethnic wealth inequalities in the U.S. originated in colonization and slavery, they have endured only because of the many legal and financial systems and policies that have been created and continue to operate to ensure this stolen wealth grows and passes to future generations. For example, the lack of reparations for slavery and land theft, investment and trust systems, inheritance and tax laws. Or, to put it more succinctly, in the words of Mehrsa Baradaran,“Wealth is where past injustices breed present suffering” (Klein & Posner, 2018, 01:05).

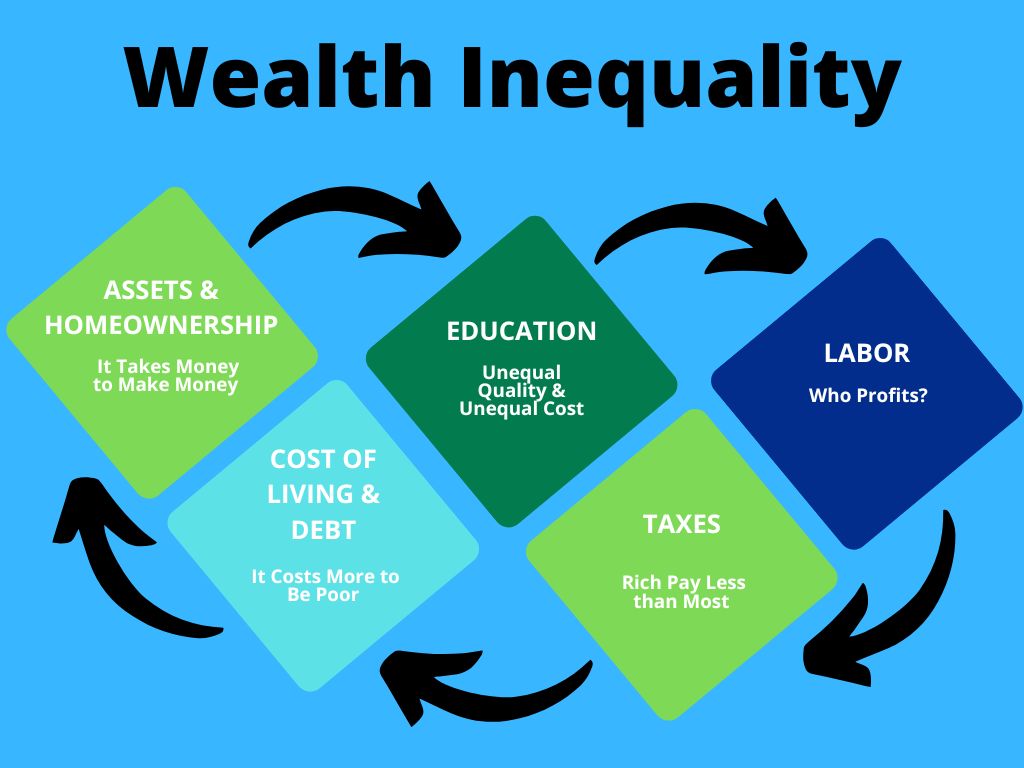

But just as importantly, current legal and financial systems also create inequities in how white and BIPOC Americans accumulate new wealth today. These systems are circular and self-reinforcing, so even as parts of the system morph and change (for example how the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968 to outlaw discrimination in lending, but it was then followed in 1982 by deregulation of mortgage lending), racial financial disparities are further entrenched.

Racial inequities are perpetuated by both formal and informal discrimination, such as a landlord choosing not to accept a Black tenant (Demsas 2021) or an employer refusing to hire anyone with a criminal record, which often function to keep BIPOC communities out of wealth-generating arenas altogether (high-salary jobs, property investment, founding businesses, stock markets, etc.).

But just as importantly, racial inequities are perpetuated by policies and practices that continue to build wealth for white Americans while stripping wealth from BIPOC communities. These wealth-building policies and practices, such as the tax, inheritance, and bankruptcy systems, and property tax protections such as those in the state of California, amount to huge subsidies and equity-builders for those who have already accumulated wealth.

In this chapter I will describe some of the economic systems that serve white and BIPOC participants unequally, such as: homeownership, which boosts the wealth of (disproportionately white) homeowners and landlords but indebts (primarily BIPOC) tenants to increasingly unaffordable degrees; the educational system, operating to boost the wealth of some (primarily white) graduates while hindering the income of others (primarily BIPOC); and the labor system, which is controlled and profited by (disproportionately white) business owners or stockholders while compensating many (primarily BIPOC) workers with an unlivable wage.

Residential Racial Segregation

Where you live greatly impacts your access to quality education and proximity to well paying jobs, increasing or decreasing accordingly one’s likelihood of escaping poverty. This correlation can actually be mapped through resources such as the Opportunity Atlas.

This leads us to the question, what does my ZIP code say about me? The answer is very complicated but to put it simply, our ZIP code determines our future in many more ways than is discussed. It is important to note that many injustices discussed in this book can be traced to where we live. For example: inequity in wealth, educational inequity, criminalization, mass incarceration, and environmental racism can be traced back to our ZIP codes. Assuming you even have a zip code.

In The Address Book: What Street Addresses Reveal about identity, race, wealth, and power, Deirdre Mask asks the following question: “how do homeless people live without an address?” In a national survey facilitated by service providers for homeless people they found that most responded what they really needed was an address (Mask, 2020). Mask details how although an address is not a home, it is an important part of our lives that allows us access to register a child to school, apply for a job, register to vote, open a bank account, and so forth. Furthermore, the study found that when homeless individuals did not have an address they were barred from applying to jobs. Some jobs where individuals in the study applied required a background check to investigate the applicant’s address history (p. 244). It is important to note that families with children make up a third of the homeless population (p. 245).

Why is Housing Racially Segregated?

U.S. residential racial segregation was developed during the early 1900s (Massey & Denton, 1993). Residential racial segregation is the separation of different racial groups to different neighborhoods. The process of residential segregation was not a natural one as it is often described to be, with people voluntarily preferring to live close to their extended families and cultures they are familiar with. Although that is certainly a factor in some amount of racial and ethnic grouping, there were many official rules and laws requiring residential segregation. Real estate boards formally prevented realtors from selling to nonwhites because they believed that the price of homes in all-white neighborhoods would increase over time. Realtors used various tactics to keep neighborhoods segregated, most notably racial covenants, steering, and redlining. Although each of these strategies have been independently implemented they have worked together to promote residential racial segregation in order to keep white neighborhoods white.

Racial covenants are a now non-enforceable contractual agreement found in the deed to a house which explicitly states that non-white people cannot own or rent the house. In other words, they are rules that homeowners or developers could add themselves to their house deed to forbid certain races from buying or living on the property, even after the property was sold or passed through inheritance. Homeowners would coordinate with their neighbors to create entire neighborhoods where only whites could live, to protect their comfort and also their property values. For example, “No lot covered by this indenture, or any part thereof, shall ever be sold . . . leased or rented to or occupied by, or in any other way used by, any person or persons not of the Caucasian Race, nor shall any such excluded person live in any main building or subsidiary building or any such lot; provided, however, that this restriction shall not be applicable to domestic servants in the employ of the owner or occupant then living in such building” (Thompson et al., 2021).

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\), a flyer titled “Only Members of the Caucasian Race,” is a perfect example of how racial covenants were used to segregate white and non-white residential areas, especially new subdivisions. It reads as follows:

One of the important features of the building regulations at Highland Park reads as follows:

the buyer agrees that no estate is or possesses of the said premise shall be sold, transferred or conveyed to any persons not of the Caucasian race.”

This means that when you buy a homesite in this property regulated home place, you will forever be assured of desirable neighbors. Only members of the white race can buy or hold property in this beautiful restricted residence park.

Another provision specifies that only dwelling houses are permitted, and these must cost at least a definite amount.

Good neighbors, beautiful surroundings, uniform improvements, and a large enough area, or residential zone, to make building regulations effective, are only a few of the many advantages of Highland Park.

This handsome park, with 332 acres is the largest restricted home district in Utah. Because of its farsighted regulations, all property will become more beautiful and more valuable each year.

Go in our auto and investigate for yourself the many advantages of locating in a regulated home district.

In 1948, the Supreme Court case Shelley v. Kraemer ruled that racial covenants were unenforceable in real estate transactions. The court didn’t find the racist covenants themselves in violation of constitutional rights (because home purchases are a private transaction), but rather that the court’s enforcement of these covenants was unconstitutional. Although racial covenants are not enforceable by courts, many homes still have these racial covenants in the “property title” because they are not easily changeable. And some fear that if they are erased, so will the evidence of this horrendous system (Kim, 2021). However, recently the process has been streamlined in California, although it is not automatic, so only time will tell if it increases the rate of removal (Kim).

Quickly after racial covenants were phased out, cities, municipalities, and counties turned to zoning to serve a similar function (Kim).

Education, Zip-Codes, and Wealth

Today, our schools are more segregated than ever through the wealth of our neighborhoods. Although Horace Mann famously called education in the U.S. “the great equalizer,” (1848, as cited in Education and Social Inequity, n.d.) it has often been used as a method to keep communities impoverished. Education is believed to be the way for individuals to rise above their social economic status. What happens when education is designed to perpetuate social economic status? Our family’s socioeconomic status predicts the quality of education we will have access to more than any other factor.

There have been many attempts to desegregate schools and to offer equal education for all, however inequities in education have persisted and transformed how students can access a quality education. Now more than ever, our zip code determines the funding for our schools, the quality of our schools and our access to wealth through education. Although Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 is often framed as the pinnacle of desegregating schools and opening quality education to black and brown students, there have been many later legal cases that significantly lessened the desegregation of schools.

Since Brown v. Board of Education there have been many efforts to further segregate schools in new ways that have pushed back against legal desegregation of schools. According to an article by Time Magazine titled “The Worst Court Decisions since 1960,” the San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez (1973) decision has been among the worst. This is an important Supreme Court decision which argued that inequity in school funding did not violate students' constitutional rights to an equitable education. The ruling legalized the funding of schools based on Zip Code wealth instead of funding equitably to historically disenfranchised communities. Furthermore, this decision legalized separate and unequally funded schools in the U.S. and still impacts how our schools are funded.

In the same article, the decision of Millikan v. Bradley (1974) is marked as one of the worst court decisions since 1960. This case effectively stopped the bussing of inner city Detroit students to historically segregated schools and getting closer to desegregating schools. This case was a major setback for the progress of Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and one of the major goals of desegregating schools. "School segregation is now more severe than in the late 1960s” (Orfield & Jarvie, 2020, p. 11). At the peak of desegregation in 1988, more than a third of Black students (37%) attended schools that had a majority of white students, and in the South, it was 43% in majority white schools. In 2018, it was down to 19% nationally, 18% in the South and only 14% in the West (p. 28). Some have argued that statistics focused on the proportion of white students at a school are misleading, because the U.S. has become more diverse, naturally lowering the percentage of white students (Stancil, 2018). But the evidence is clear: entire school districts are becoming more racially distinct from each other, even while racial diversity within those districts may be increasing (Stancil). The share of Black students in segregated schools has increased by 11 percent nationwide in the last two decades, faster than the share of either white students or nonwhite students overall, which have both risen by about 6 percent (Stancil).

Of course, school segregation is intimately tied to homeownership, both because public schools are funded by local housing taxes, so the higher the home values, the more-resourced the schools, but also because many wealthy communities have little rental housing, and what does exist is exorbitantly expensive. In the next section, we will explore in more detail why there are racial inequities in homeownership, which fuel both school segregation but also how this widens disparities in assets and new worth.

Racial Inequity in Homeownership

Housing, land, and the history of segregation has arguably caused the greatest amount of damage to access to wealth. This chapter will emphasize how housing access, specifically owning land and a home, is the biggest component of wealth for many families (Bhutta et al., 2020). This chapter will also focus on the historical disenfranchisement by laws, policies, and practices that have been utilized to further the racial wealth gap.

Historically, the most common method for families in the U.S. to build wealth has been through real property (land and homes). Some families have inherited property originally granted from the English or Spanish crown when the U.S. was still made up of colonies, through the Homestead Act, or later through the G.I. bill (all of which were given almost exclusively to whites only), or property purchased by their ancestors.

For most others, the greatest wealth they will accumulate in their lifetime is by purchasing a home.

On the one hand, the ability to purchase a home is a reflection of wealth a family already has (or their parents' wealth), as significant funds are generally required for a down payment and closing costs. On the other hand, homeownership has also been found to yield strong financial returns on average and to be a key channel through which families build wealth (Bhutta et al., 2020, citing Laurie S. Goodman and Christopher Mayer’s 2018 article "Homeownership and the American Dream").

Unfortunately, many BIPOC families have been explicitly barred from purchasing or financing a home in thriving communities where real estate prices rise over the years, creating equity. This has created wealth inequality and a lack of equity in BIPOC communities.

A good testimony on the power of having access to generational income through family home ownership is the story of Cory Booker, a current U.S. Senator from New Jersey. Booker narrates his family's story in the Netflix show “Explained,” Episode 1, “The Racial Wealth Gap” (Klein & Posner, 2018). He recalls that without a doubt his family's access to purchasing a home in a desirable neighborhood laid a foundation for intergenerational wealth that allowed Booker to become a U.S. senator.

Booker's experience reaffirms many of the things we will be discussing in this chapter including redlining, unfair practices by realtors, and racial covenants. Booker's parents knew that having access to purchasing a home in a desirable neighborhood would open up opportunities for their children. However the laws, policies, and racist practices would have prevented his parents from buying a home in their desired neighborhood. In this story, Booker tells us that his parents had to trick the realtor after they had been denied an opportunity to put an offer on their desired home. His parents met with a white lawyer who made an appointment to see the house and put an offer on behalf of the family without the realtor knowing. Once Booker's family arrived to pick up the keys, the lawyer and the realtor ended up fighting. The realtor begged that the family not move into the home because it would damage his business.

The Booker family story is important when exploring the experiences of African American families that were able to access wealth through the real estate market. Furthermore, their story leads us to ask the question: "how many other families have been turned away from purchasing a home in their desired neighborhood?" Although it may be nearly impossible to find an exact number of families turned away from viewing a home in a greenlined neighborhood, it is imperative to know the stories of families who have been pushed aside from accessing generation wealth vis-à-vis the real estate market. Moreover, by looking at segregated and redlined neighborhoods, we can draw connections between experiences by predominantly African American and Latinx families.

Redlining

Redlining is the practice of automatically denying mortgage loans based on a property’s geographic (redlined) location, rather than assessing an individual’s creditworthiness. Historically, the areas that were considered undesirable and were redlined were the areas where BIPOC residents were allowed to live, and the desirable (sometimes “greenlined” or “bluelined”) neighborhoods were limited to white residents through racial covenants. This meant that even middle- and upper-income African Americans and other BIPOC could not receive a loan to purchase a house anywhere, while a lower-income white borrower could be approved to purchase a home in a greenlined area.

Unable to get regular mortgages, Black residents who wanted to own a house but did not have enough funds to purchase one in cash were pushed into rent-to-own housing contracts that massively increased the cost of housing and gave them no ownership rights or equity until their last payment was accepted (and it was often not, for one reason or another). Many testimonies of those who endured this system are shared in the article by Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Case for Reparations” (2014), discussed in section 9.5, under: “The Ongoing Struggle for Reparations.” Redlining and its legacy created the basis for educational disparities to persist even after racial covenants were outlawed, and greatly weakened the BIPOC homeowner base and therefore equity and intergenerational wealth for whites accrued over time.

Although redlining was subsequently outlawed, it still is practiced in new permutations, and was widely cited as part of what created the housing crash of 2008. The housing crash of 2008 was a bubble caused by racially predatory lending which “popped,” wreaking havoc on financial markets while draining housing assets from largely Black and Latinx communities. Redlining was important because it is a basis for educational disparities even after racial covenants were outlawed. It greatly weakened the BIPOC homeowner base and therefore equity/ intergenerational wealth. For example Atkinson expands on the effects of the subprime mortgage crisis, writing,

The subprime mortgage crisis that helped bring on the Great Recession resulted in the decimation of housing-related wealth among economically disenfranchised groups and communities. These losses were, in significant part, the direct result of the rampant racialized and geographic mortgage discrimination that took place in these communities in the run-up to the financial crisis and persists today (Atkinson, 2015, p. 1041).

Unequal Education

Education in the U.S. is widely seen as the method to accessing wealth by having access to a desirable career. Some believe that education can eradicate poverty. What is the real purpose of education in the US? K-12 education and higher education in particular have promoted the idea that education is a critical method for social mobility. But as we saw earlier in this chapter, where we live and our zip codes often dictate the quality of education we have access to.

Educational tracking has also been used by the U.S. hegemonic class which is a method to track racialized students throughout the educational pipeline to not attend college by simultaneously preparing them for menial jobs or semi-skilled labor. Many scholars agree that students of color are disproportionately criminalized and “pushed out” of K-12 education and into the school-to-prison pipeline (Rios, 2011).

Nevertheless, for some racialized people in the U.S., educational achievement has been used to have access to higher paying jobs and achieve other markers of wealth, such as homeownership. Although countless disadvantaged students have achieved social mobility and earn higher wages through completing higher education, even more have been pushed away through racially-disparate educational barriers.

Education has always been used for cultural agendas as well as academic ones. Schools were used to further colonize American Indian children through the use of Native American boarding schools (please see the section "Assimilation, Boarding Schools and Adoption" under Chapter 4, section 4.4: "Invasion, Occupation, Imperialism, and Hegemony). Native American boarding schools were used to convert Native American children to Christianity and simultaneously lose their native culture. Methods used to forcibly assimilate Native American children were not allowing them to speak their native language, practice their religion and spirituality and enforce gender rules that fit in the western culture. For example, young Native American boys' hair were cut short and they were relegated to working outside doing physical labor such as farming and other physical labor. Whereas young Native American girls were pushed to work inside of the home and learn how to cook, clean and keep a home then sent off to work in white homes.

In her opinion piece titled "let's talk about Harvard Colonial past and present," Ariel G. Silverman writes about Harvard University's Native American program which eventually created the Harvard Indian college established in 1655. The Harvard Indian college further progressed the project of assimilating Native Americans to U.S. dominant culture. Additionally, the college was home of one of the first printing presses in the English colonies and it was used to print Bibles in Native American languages (Lopenzina, 2012). Silverman ties the history of Harvard’s Indian college to the larger history of settler colonialism and white supremacy in the U.S. where “the ideology that white people and their ideas, thoughts, beliefs, and actions are superior to people of color and their ideas, thoughts, beliefs, and actions” (Silverman, 2021). Lastly, it is important to note that Harvard also has a history of using slave labor to serve faculty, administration, and students (Binkley, 2022).

In addition to cultural agendas, education has been used to further economic ones. The public education system in the U.S. was established on the tail end of the industrial revolution. As the world got smaller through transportation advances such as the train and the car, young people needed to be literate in order to participate and be productive members of society. This is the beginning of public education as we know it today. Before the Industrial Revolution, education was the private responsibility of families and parents who organized how to educate their own children. It is important to note that after the Industrial Revolution, we saw the rise of schooling as organized education (Spring, 1989). As a national project, education has been viewed as increasing national wealth by creating a literate population and advancing technology. This happens by socialization of the future work force and by the sorting and training of the future labor force (Spring, 1989). Spring emphasizes that the goal of socialization for the workplace has been part of the project of public education in the U.S. throughout history.

Early on, the purpose of education was not to create a population of critical thinkers or to lay groundwork towards wealth but to create more workers that can already be accustomed to accepting orders. For example, the 19th century American Education system supported marching, drill, and orderliness and it was “justified in terms of training for factory assembly lines” (Spring, 1989). As mentioned in the beginning of this section, the purpose of education is for the dominant group to impose their political goals onto populations, thus reinforcing cultural hegemony onto the students. Coined by Antonio Gramsci, cultural hegemony is widely accepted as domination through coercion or consent. It is important to ask what is being taught in schools that ultimately benefits the dominant (wealthy, political) class.

Racial Capitalism

Racial Capitalism is a theory developed by Cedric Robinson in which he states that

capitalism and racism, in other words, did not break from the old order but rather evolved from it to produce a modern world system of “racial capitalism” dependent on slavery, violence, imperialism, and genocide. Capitalism was "racial" not because of some conspiracy to divide workers or justify slavery and dispossession, but because racialism had already permeated Western feudal society (D.G. Kelley, 2017).

In other words, it helps us understand the legacy of capitalism in the U.S. and how modern racialized labor is an updated manifestation of the racist ideologies infused within racial hierarchies.

Racialized labor is important to understand because it is the ontological experiences that attempt to enforce social orders of the past. In other words, how does labor today shape our existence? How is it informed from history? Labor functions most commonly as the selling of time, effort, blood and sweat in exchange for money while simultaneously making profits for someone else. The profits are always more than the labor is compensated for. It is also important to note that Robinson "encountered intellectuals who used the phrase “racial capitalism” to refer to South Africa’s economy under apartheid (D.G. Kelly, 2017).

How are our bodies racialized and exploited based on the legacy of white supremacy? In the U.S. racialized labor has been exploited and used to build the country, especially forced enslaved labor from Black Africans which became one pillar to white supremacy in the US. Labor has simultaneously been utilized as a method for making the exploiters of labor wealthy and to keep laborers in a controlled social space (economic, segregation, education, and psychological). Race, as defined by Michael Omi and Howard Winant, helps us to add more substance to connect how we are racialized to past history and how it informs our racialized experiences right now. Omi and Winant define race as “a concept which signifies and symbolizes social conflicts and interest by referring to different types of human bodies” (Winant & Omi, 1994, p.55).

In his article “How Capitalism and Racism Support each other” economics professor Richard Wolff agrees with Cedric Robinson on how race functions in capitalism. Wolff agrees because he states that “every capitalism that we know of has always demonstrated a desperate, urgent, and ongoing desire to do what business schools call ‘economizing on labor costs’ (Wolff, 2016). That’s a polite way of saying - trying to figure out how to get away in the production process with paying less for the labor you need to hire to complete the process of production.” Historically, U.S. capitalism has utilized many methods to acquire free labor or to keep labor costs down such as slavery, child labor, racialized labor, immigrant labor, transnational labor, globalized labor, non-union labor, gig economy labor, automated labor, etc. Furthermore Wolff shares an example that racialized labor is taken advantage of especially when there is an incoming immigrant group with a different culture and treated like second class citizens and oftentimes used as scapegoats. According to Wolff’s analysis, racialized labor becomes a function of capitalism that is used as “the shock absorbers of capitalism’s instability, and that’s why capitalism works as hard as it does to maintain them and if not someone else in that role” (Wolff, 2016).

The results of racial capitalism have been punishing as summarized in the quote below:

Black boys raised in America, even in the wealthiest families and living in some of the most well-to-do neighborhoods, still earn less in adulthood than white boys with similar backgrounds, according to a sweeping new study that traced the lives of millions of children. White boys who grow up rich are likely to remain that way. Black boys raised at the top, however, are more likely to become poor than to stay wealthy in their own adult households. Even when children grow up next to each other with parents who earn similar incomes, black boys fare worse than white boys in 99 percent of America. And the gaps only worsen in the kind of neighborhoods that promise low poverty and good schools (Badger et al., 2018).

Employment disparities along racial lines have resulted in Black Americans losing out on $220 billion in wages they would be earning annually if their occupational numbers across business sectors were proportional to their percentage of the U.S. population (Alcorn, 2021). Black Americans are concentrated in lower-wage occupations and underrepresented in higher-paying careers (Alcorn). For example, Black workers, who represent 13% of the population, make up just 5% of the nation's physicians and 4.5% of its software developers (both highly-paid), yet are roughly 35% of all U.S. nursing assistants (an occupation with a median wage of just $23,000), and 33% of all security guards and school bus drivers (Alcorn).

Labor Unions

The struggle of labor and power has persisted in what is now the US since the initial contact with European Settlers. In his book, A People's History of the US: From 1492 to Present, Howard Zinn provides the background of the relationship between Virginians in 1617 and Native Americans. One of the premises of this relationship was the European settlers plotting to exploit indigenous labor. Zinn writes,

They couldn’t force Indians to work for them, as Columbus had done. They were outnumbered, and while, with superior firearms, they could massacre Indians, they would face massacre in return. They could not capture them and keep them enslaved; the Indians were tough, resourceful, defiant, and at home in these woods, as the transplanted Englishmen were not (2015, p. 25).

Nevertheless indigenous people were enslaved in the Americas and “African blacks had been stamped as slave labor for a hundred years” (p. 26). This era of race and labor informs the representation or lack thereof Native American and Black labor in future labor movements because “the color line also subtly marked even… labor unions, which privileged whites over working-class people of color despite ideologies of equality” (Redmond et al., 2016, p.421). Ultimately racial and social identities have a basis where they impact who gets “the jobs, who owns homes, who gets racially profiled (p.242).

In the U.S. labor organizing has historically been met with suppression by employers who benefit from the profits the labor produces. According to the Department of Labor (DOL) a labor union is:

a group of two or more employees who join together to advance common interests such as wages, benefits, schedules and other employment terms and conditions….Unions are membership-driven, democratic organizations governed by laws that require financial transparency and integrity, fair elections and other democratic standards, and fair representation of all workers (Unions 101, n.d.).

Although union organizing greatly benefits its members through collective bargaining in order to achieve its goals. BIPOC have been excluded at times from benefiting from labor unions. For example the president of AFL (American Federation of Labor), Samuel Gompers, in the early 1900s claimed that he only knew a few instances where “colored workers were discriminated against” and he blamed them “for their depressed economic condition in order to exonerate the discriminatory actions of his union” (Kendi, 2016, p. 274).

There are too many union organizing movements throughout U.S. history to analyze in this chapter. Fast forward to 2023, there has been a rise in labor organizing struggles. From teachers to Amazon workers and many other labor sectors have been fighting for collective bargaining rights. Labor unions have been under attack because they have been labeled as bad for business and ultimately bad for the consumer because of the “rise in production costs”. Unions can produce the opposite effect, which is the best thing for consumers and good for business. How do these recent labor movements reflect the tainted histories of labor organizing in the past? How are these histories being reproduced? How are they being challenged?

The labor demographics in Amazon’s workforce affirm the racialized labor exploitation which can be found in US labor organizing history. Did you know that “more than 60% of the nearly 400,000 U.S. workers Amazon hired into its lowest-paying hourly roles between 2018 and 2020 were Black or Hispanic, and more than half were women” (Long, 2021). Only about 18% of the corporate and tech are Black, Indigenous, or Latinx. Although Amazon is the second largest company in the US “its average starting wage is now $18 — the wealth generated by the company has largely not trickled down to its hourly workers, those employees say” (Long, 2021). Furthermore, “racial inequities were at the forefront of the union campaign, nearly 80% of the employees at the Bessemer [Alabama] warehouse are Black” (Long, 2021). Aside from the racial makeup of Amazon employees, most are designated to part time status and if they do work full time it is most likely during the holiday season.

Against all odds Amazon Labor Union (ALU) became a reality on April 1st, 2022 for Amazon workers at JFK8, a Staten Island Amazon fulfillment center, with the leadership of both Chris Smalls and Derrick Palmer (Tarasov, 2022). Their labor organizing efforts were met with the pushback of Amazon attorneys who filed 25 objections to the election results. One of Amazon’s objections claimed that “union leaders bribed workers with marijuana” and another objection stated that the union leaders “harassed those who didn’t support the union” (Tarasov, 2022). On the ALU website they state:

Our demands are simple: better pay, better benefits, and better working conditions. Amazon workers know the only way we’re going to pressure the company into treating us with respect is by uniting under one banner and exercising our right to come together as an independent union (ALU Website, 2022).

The ALU experienced and continues to experience countless struggles against expanding their organization to other Amazon warehouses.