4.3: Narratives, Representation, Epistemic Violence, and Healing

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 138204

- Mario Alberto Viveros Espinoza-Kulick & Melissa Moreno

- ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Dominant Narratives in the Representation of Native American and Indigenous Histories

When was the last time someone told you that you are important, your Indigenous ancestors matter, and that you can make a difference in your community? Worldwide Indigenous peoples have emphasized the value of community survivance. The reality of Indigenous peoples living and thriving in the contemporary global society while affirming their dignity and resisting neocolonial systems of oppression continues. In this section, you will learn more specifically about contested narratives of Native Americans and Indigenous Peoples. For example, this includes a recognition of the solidarity between Chicanx and Indigenous struggles such as in the 1992 protest of the 1994 Columbus Celebration in the U.S., the struggle against the PeaBody Coal Mining Industry in reservations, and more recently Standing Rock against the DAPL.

The saying “Indians are dead” is part of a master narrative that continues to circulate in schools and society. We refute that Indigenous people are dead or have disappeared. In the western hemisphere, Central America and the southern part of Mexico are home to the largest number of living Indigenous people today. In addition, people who self-identify as Chicana/o/x, Latina/o/x, Puerto Rican, Central American, and South American often have ancestors with Indigenous roots and they carry on their cultures, languages, traditions, and lifeways. Roberto “Cintli” Rodriguez and others have referred to members of this group as la Raza, which means people whose genetic matter has been in this hemisphere for thousands of years.

For many years, American and European scholars have presented the Bering Strait Theory to describe and categorize Native Americans as migrants to this country. This follows the logic of an “Out of Africa” hypothesis of human evolution, which postulates that modern human beings emerged from a single pair of genetic ancestors living in Africa, in an approximate location that would match the Bible’s description of the Garden of Eden. This theory suggests that humans arrived in the Americas about 15,000 years ago by migrating from Asia over through the Bering Strait, a land bridge between what is today called Russia and Alaska. This area was passable by land at the time, although it is covered in the ocean today. Native Americans and Indigenous people do not describe themselves as migrants from another place but have scientific and cultural knowledge of originating in their homelands. As Indigenous scholar and activist Vine Deloria has argued, along with other scholars and critics, there are increasing amounts of archeological and scientific evidence that refute the Bering Strait Theory, suggesting that the Bering Strait was unpassable until about 12,600 years ago, which is after documented human life had spread throughout North and South America.20

The connection to the homeland is represented in creation stories. Each tribal community represents their ethics of stewardship and tending the land and culture in their stories. This is true and important for Indigenous people across the hemisphere, as noted in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. This historic document sets the precedent for international law and the need to recognize the collective rights and sovereignty of Indigenous peoples on their land. It is available online on the United Nations website. In specific tribal community contexts, creation stories refer to the ecology and often center on a significant relative in the region, such as ants, badgers, birds, condors, corn, eagles, ravens, serpents, turtles, whales, and specific mountains. Stories of Indigenous heritage are shared through oral history. These stories carry important values, beliefs, sensibilities, and dispositions on ecology, life, death, and regeneration. These stories reflect the diversity within Indigenous peoples, their land, and cultural pride.

Cultural Spotlight: Cahuilla Bird Songs

Bird Songs are a part of the California Native American traditions including the Cahuilla people located in southern California,. The practice of Bird Songs in celebrations, community gatherings, and ceremonies helps to communicate a continued cultural tradition that is rooted in ancestral knowledge. The documentary, “We Are Birds: A California Indian Story” by Albert Chacon, which is available on YouTube and licensed CC BY 3.0, demonstrates these practice real-time. The full documentary is one hour, seven minutes, and ten seconds.

Activity: Indigenous Land Website

Stories of Indigenous heritage are shaped by the specificity of each group’s creation story or creation story reflecting traditions and responsibilities tied to their people’s land, ecology, and/or sacred spaces. You can learn more about the Indigenous peoples of various lands throughout the world by visiting the Native Land map website. This is a secondary collection of territories and Indigenous peoples, which includes links to primary sources and information on Indigenous tribal lands. You can search by address, and one interesting place to start can be by exploring where you are currently residing or studying.

Struggles for Truth and Accountability in Cultural Narratives

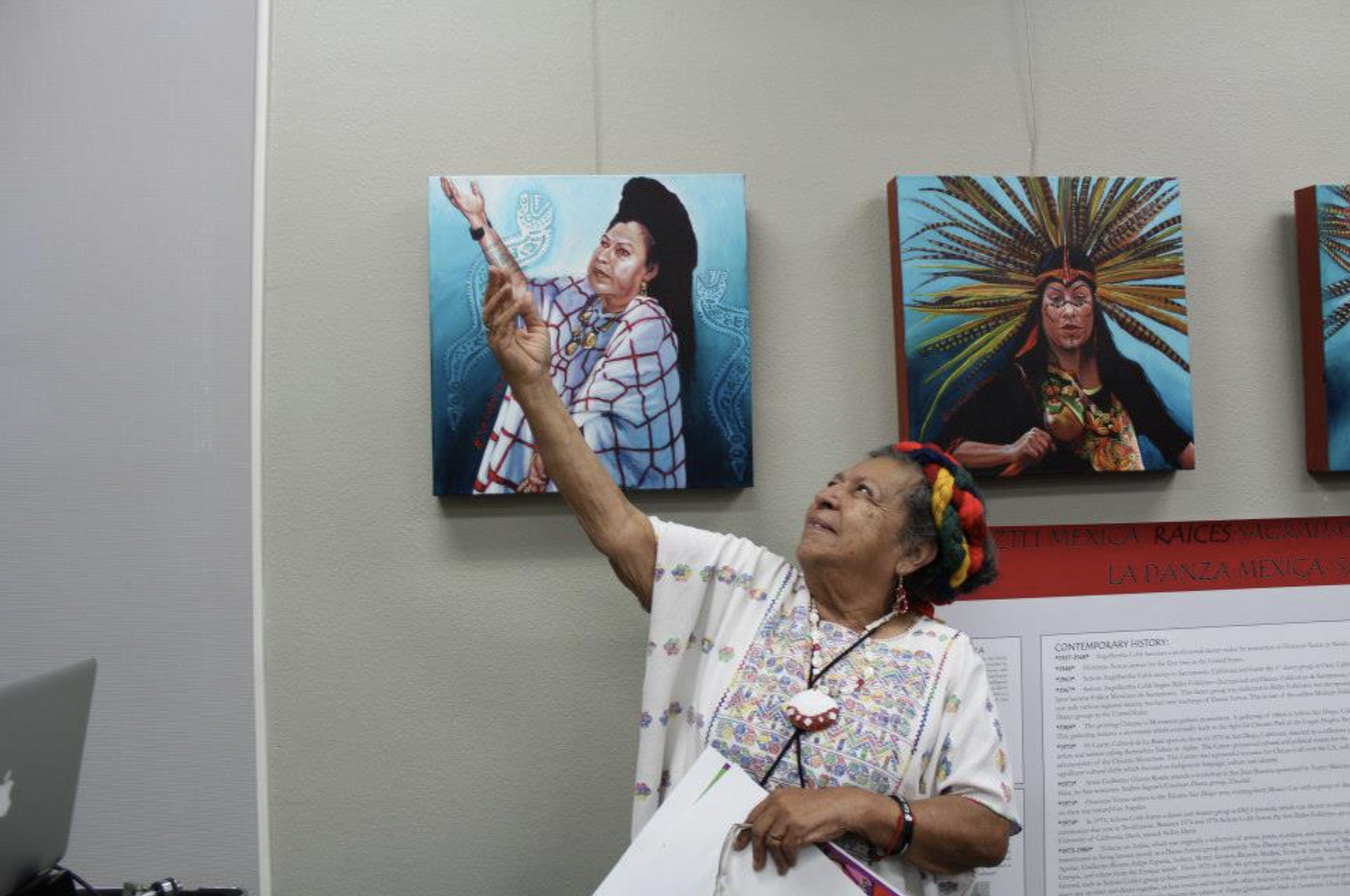

Queer Chicana author Gloria Anzaldúa based her work on the knowledge of Native American studies scholars like Jack Forbes to represent the Indigenous realities of mestiza/o/x peoples. Her book Borderlands/La Frontera was first published in Spanglish and represents the sensibilities of mestizas, including topics like Indigeneity, Nepantla, Two-Spirit duality, and fluidity of gender, and colonial gendered morality. These areas of inquiry are carried on by young people and elders who work together to carry on their Indigenous traditions. Among the Indigenous cultural work Elder and Capitana of Danza Mexica Azteca Angelbertha Cobb, who is pictured in Figure 4.3.1. She posed in front of an artistic rendition of La Malinche, mother of the first mestizo, her same gesture and position. In Mexico City, Cobb was close friends with Frida Khalo and Diego Rivera and also directly benefited from the efforts of President Lazaro Cardenas, who recruited her as one of the best Indigenous dancers in the highland of Puebla. Cultural workers like her, and the work of other Indigenous cultural groups have helped to sustain and communicate traditional knowledge through art, dance, and dress.

Figure 4.3.1: “Elder Angelbertha Cobb, Mexica Danza Capitana, painted as La Malintzin Tenepal as known as La Malinche” by Melissa Moreno, Author is licensed CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Solidarity across Indigenous and non-Indigenous people have been key to the survivance of Native peoples.21 Survivance refers to the collective process of survival, which carries forward the culture, peoples, and land beyond the individual. For example, since the early 1970s, a segment of Chicanxs, aware of and attached to their Indigenous roots, have participated in and supported the United Nations Committee for Advancing Indigenous Peoples’ Rights and Cultures Worldwide. Chicanxs and Latinxs people who support solidarity with Indigenous peoples have supported self-determination, cultures, and political resilience. Through the emergence of ethnic studies, Chicanx and Latinx studies, Native American studies, and the American Indian Movement (AIM), there has been an increase in awareness of various Indigenous movements. These movements share a commitment to Indigenization, supporting revitalization of Native languages, ancestral foodways, medical use, cultural burnings, midwifery traditions, dances, coming-of-age ceremonies, land acknowledgment, and more.

In order to effectively support decolonization, it is necessary to cultivate knowledge of diverse tribal groups. Awareness and education in the US of Indigenous and Native peoples, both past and present, can be attributed to the legacy and efforts of the civil rights movement, the American Indian Movement, Native American studies, and Chicanx and Latinx studies, as well as global Indigenous movements. Some examples include Sandinistas, Zapatistas, and water protection.22 In the context of the 1960s civil rights movement, there was a call to end institutional racism and colonization, to go beyond Eurocentric curriculum/knowledge, and for self-determination. With this came the emergence of ethnic studies and Native American studies at colleges and universities, which studied and deconstructed the colonial master narrative and connotation of triumphalist narratives of white supremacy and settler-colonialism, including holidays like Columbus Day.

For 500 years, the master narrative surrounding Columbus stood in the United States. Columbus Day became a federal holiday in the 1930s, however, several communities across the U.S. have come to realize and recognize the truth surrounding the violent domination and oppression that led to the slavery and genocide against Indigenous people in the Americas. Interestingly Indigenous Peoples Day, known as “Dia de La Raza” in Latin America and Mexico, has been recognized since World War I. In the United States, in many states and cities, Columbus Day has been replaced with Indigenous People’s Day, after many protests and efforts of advocacy. For a deeper exploration of this developing history, the next section goes into more depth on the timeline of these movements.

A Timeline of Solidarity between Chicanxs and North American Native Americans

Given the lack of California homeland education, in 1969 the California Indian Education Association established the Annual California Indian Conference to begin focusing on curriculum and educational issues impacting California Indian students and tribal communities.

- In 1973, the American Indian Movement members and their allies met and decided to form the International Indian Treaty Council (IITC) to seek justice in the United Nations. In July 1990, Indigenous Chicanxs and Latinxs participated in the Indigenous Encuentro in Quito, Ecuador, where they had a seat at the table.

- In 1992 the IITC, which included Indigenous Chicanxs, stood strongly against the United States celebrating the 1492 invasion of Columbus. Indigenous people from across the Americas stood strongly in opposition, vowingnot tot celebrate the genocide of their ancestors through the proposed Columbus Day Celebration. The IITC and others raised awareness about the implications of genocide and the Doctrine of Discovery of Indigenous people. Political artists like Aztlan Underground and various Mexica Aztec Danza groups supported this movement as well.

- In 1994 the Zapatista uprising and social movement that Chicanx supported began in response to the oppression and domination by the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement. NAFTA altered the Mexican Constitution so that ejido plots of land could be sold to foreigners, where in the past it had been illegal.

- In 1995, some Chicanxs learned first-hand about resistance to environmental destruction by mining companies from the Diné Navajo Grandmothers. Chicanxs were invited to be a group of protectors for the Grandmothers from a coal mining company attempting to occupy their land. On the reservation, they learned about the historical resistance to genocide, toxic pollution in water, and nuclear waste to the environment.

- In 1998 California Native American Day was established and continues today to teach people of all ages about the tribal culture, histories, and heritage of California Native American tribes. In the same year, the State Board of Education adopted academic content standards for history-social studies but did not recognize the genocide of Native Americans. Then again in 2000, the California Department of Education did not recognize the genocide of Indigenous people in the model curriculum for human rights and genocide.

- In 2007 Josefina Medina and Rufina Juarez participated at the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues with La Red Xicana Indigena, an Indigenous women’s network, to present a Special Rapporteur on Migration Issues and food sovereignty.

- By 2007 the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP), supported by the IITC, was completed and signed by all member countries in the United Nations. The U.S. was the last to sign. UNDRIP recognizes the history and contemporary experience of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Article 14 recognized the right to education without discrimination and access to cultural knowledge.

- In 2012, the Idle No More movement was born out of resistance to policy surrounding land and water impacting First Peoples in Canada. Native Americans, Indigenous peoples of the Americas, and allies including Chicanxs supported this movement across contemporary settler borders. The conversation about genocide, land invasion and the importance of Indigenous cultural pride was highlighted throughout this movement, and continued into the United States

- In community gathering spaces formed within protest sites, from 2016 to 2017, the Standing Rock Sioux tribe, water protectors from several Native American tribes, and Indigenous Peoples from across the hemisphere -- including South and Central America and Mexico -- came together to resist the Dakota Access Pipeline. They provided lessons about resistance to environmental destruction, intergenerational trauma, and survivance. These understandings were shared with thousands of families, allies, and media reporters for an entire year and beyond.

- In terms of cultural sovereignty and cultural revitalization, in the context of Indigenous Latinxs in California, we have observed a move toward bilingual and trilingual education, including English, Spanish, Mixteco, and other Indigenous languages. In 2017, First Nations launched the Native Language Immersion Initiative to support new generations of Native speakers and positive role models for young people. Some of these efforts are documented by the Oaxacalifornia Reporting Team.23

- In 2017, Maylei Blackwell, Floridalma Boj Lopez, and Luis Urrieta Jr. published a special issue on “Critical Latinx Indigeneities” in the academic journal, Latino Studies. This helped to establish the importance of considering the dynamics of Indigeneity more closely among Indigenous Latinx populations.

- In 2019, the California Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum Advisory Committee convened at the California Department of Education in Sacramento and began with a land acknowledgment. The first draft of the high school curriculum was the first ever to recognize the genocide and survivance of California Indians and Indigenous people. Chicanx that served on the committee, originally included a lesson about land acknowledgment and protection of sacred sites, but they were phased out.

- By 2022 the Indigenous Mayan-inspired poem, In Lak’Ech, was removed from State Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum. Currently, the Liberated Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum is creating more Native American Studies lessons on topics such as environment, citizenship, and culture, compared to the State Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum for various grade levels.

20 Jr, Vine Deloria. Red Earth, White Lies: Native Americans and the Myth of Scientific Fact. First Edition. Golden, Colo: Fulcrum Publishing, 1997.

21 Philip J. Deloria, “Indigenous/American Pasts and Futures,” Journal of American History 109, no. 2 (September 1, 2022): 255–70, https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jaac231; Vine Deloria Jr., “Alcatraz, Activism, and Accommodation,” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 18, no. 4 (January 1, 1994): 25–32, https://doi.org/10.17953/aicr.18.4.34k28482k49m5145.

22 Mariana Mora, Kuxlejal Politics: Indigenous Autonomy, Race, and Decolonizing Research in Zapatista Communities (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2017).

23 Oaxacalifornian Reporting Team / Equip de Cronistas Oaxacalifornianos [ECO], “Voices of Indigenous Oaxacan Youth in the Central Valley: Creating Our Sense of Belonging in California” (Santa Cruz, CA: UC Center for Collaborative Research for an Equitable California, July 1, 2013), https://www.academia.edu/4398867/Voices_of_Indigenous_Oaxacan_Youth_in_the_Central_Valley_Creating_our_Sense_of_Belonging_in_California.