4.2: Indigenous Histories, Wars, Imperialism, and Migration

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 138203

- Mario Alberto Viveros Espinoza-Kulick & Melissa Moreno

- ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Definitions and Theories of Migration and Indigeneity

🧿 Content Warning: Physical Violence. Please note that this section includes discussions of physical violence.

Indigenous people in Mexico and throughout Latin America impacted by invasions since 1492, imperialist wars, settler economies, and environmental destruction have had to engage in global migration in order to sustain their families and communities. Theories of migration and identity formation rooted in sociology, political science, and immigration studies have often tried to separate or misrepresent the realities of Indigenous people, including the presence and importance of Latinx Indigeneities.16 Chicanx and Latinx studies scholars, especially Indigenous scholars, offer a more holistic and clear understanding of the historical and conceptual background for understanding conflict, war, and migration throughout history and today.

To understand the experience of Chicanx and Indigenous Latinx peoples, it is important to understand systems of colonization and settler colonialism. Colonization refers to the action of overtaking control of another group’s territory by force using social, cultural, psychological and religious forms of domination. More specifically, the project of settler-colonialism refers to ongoing processes where the colonizing groups seek to eradicate and erase the people living in the territory they are colonizing and replace the Indigenous population with the settler population. For example, while European countries colonized parts of Asia and most of Africa, settler-colonialism is carried out in places like the Americas, Australia, South Africa, and Israel. One key aspect of settler colonialism is attempted genocide, which refers to a project trying to eradicate an entire population. This is accompanied by an ideologically rooted practice of dehumanization to justify and legitimize such actions. Multiple forms of genocide that Indigenous people have experienced have been identified by the United Nations.

Factors influencing an individual or community’s likelihood to migrate away from their current residence can include things like the inability to get a job, fear of violence, environmental degradation, or loss of family, as well as the characteristics of the receiving country, which can include things like the demand for migrant labor and the presence of jobs and housing. In the context of Indigenous migrants’ experiences, land displacement, deterritorialization, war, and colonization can separate families across national lines, leading to specific networks and pipelines that facilitate circular migration and enduring transnational ties. As well, Indigenous peoples construct complex transnational identities, which include critiques of settler and colonizer forces that operate through nationalism and federal governments.

Displacement can lead to de-Indianization, which refers to the processes of hegemony that disrupt the livelihood of Indigenous peoples, through assaults on foodways, herbal medical resources, and cultural sensibilities.17 Systems of oppression by the dominant culture impact inter-and-intra-group relations as well this means affect their collaboration and conflict within and across groups. Also, de-Indianization can manifest in individuals being denied the opportunity to practice Indigenous heritages, languages, and traditions. This can also manifest in simple ways, like families hiding or ignoring their Indigenous heritage. It also results from historical, political, and transnational factors. For example, in some cases, major displacements of Indigenous Latinx communities took place during the 1842 US-Mexican Wars on both sides of the current border, the 1910 Mexican Revolution, the 1970s in Latin America, and in Central America during the 1980s as part of the US Cold War.

Imperialism, War, and Latinx Migrations

🧿 Content Warning: Physical Violence. Please note that this section includes discussions of physical violence.

In Mexico, Indigenous peoples have endured and resisted multiple waves of empire and colonization for hundreds of years. Prior to the arrival of Spanish colonizers, much of central and southern Mexico, along with central America, was claimed by the Aztec empire. Notably, the Purépecha people (whose land is located in the state of Michoacan, Mexico) were one of the only groups to successfully resist and expel Aztec domination. During the period of Spanish colonization, many Indigenous groups worked toward the goal of liberation and independence, including participating in the Mexican War of Independence, which ended in 1821.

Another form of resistance by Indigenous peoples and mestizos took place with the war against Spain from 1810-1821. The new Mexican nation built off of the culture and standing of the Aztecs by including the eagle in its flag and basing its name on the Mexica region and Mexico City, a seat of power for Aztec elites. However, throughout the 1800s, multiple Indigenous groups, such as the Comanche, Apache, Purépecha, Yaqui, and Maya, continued to engage in resistance against the nationalist project and the expansive powers of the federal Mexican government. This widespread violence prompted many communities to migrate from their homelands to new communities and settlements.

In 1845, the United States government annexed Texas, which was considered an act of war by the Mexican government. A year later, in 1846, the U.S. Congress formally declared war on Mexico, at the request of President Polk. The U.S. was motivated by a desire to expand its territory westward, under the ideology of “Manifest Destiny,” which is the idea that the United States had a divine imperative to colonize the entire continent, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean.18 Internal politics in the United States were also focused on the presence and expansion of slavery, with many of the northern states and the Northwestern territories outlawing slavery, while southern states defended the institution and sought to expand it into new areas like Texas.

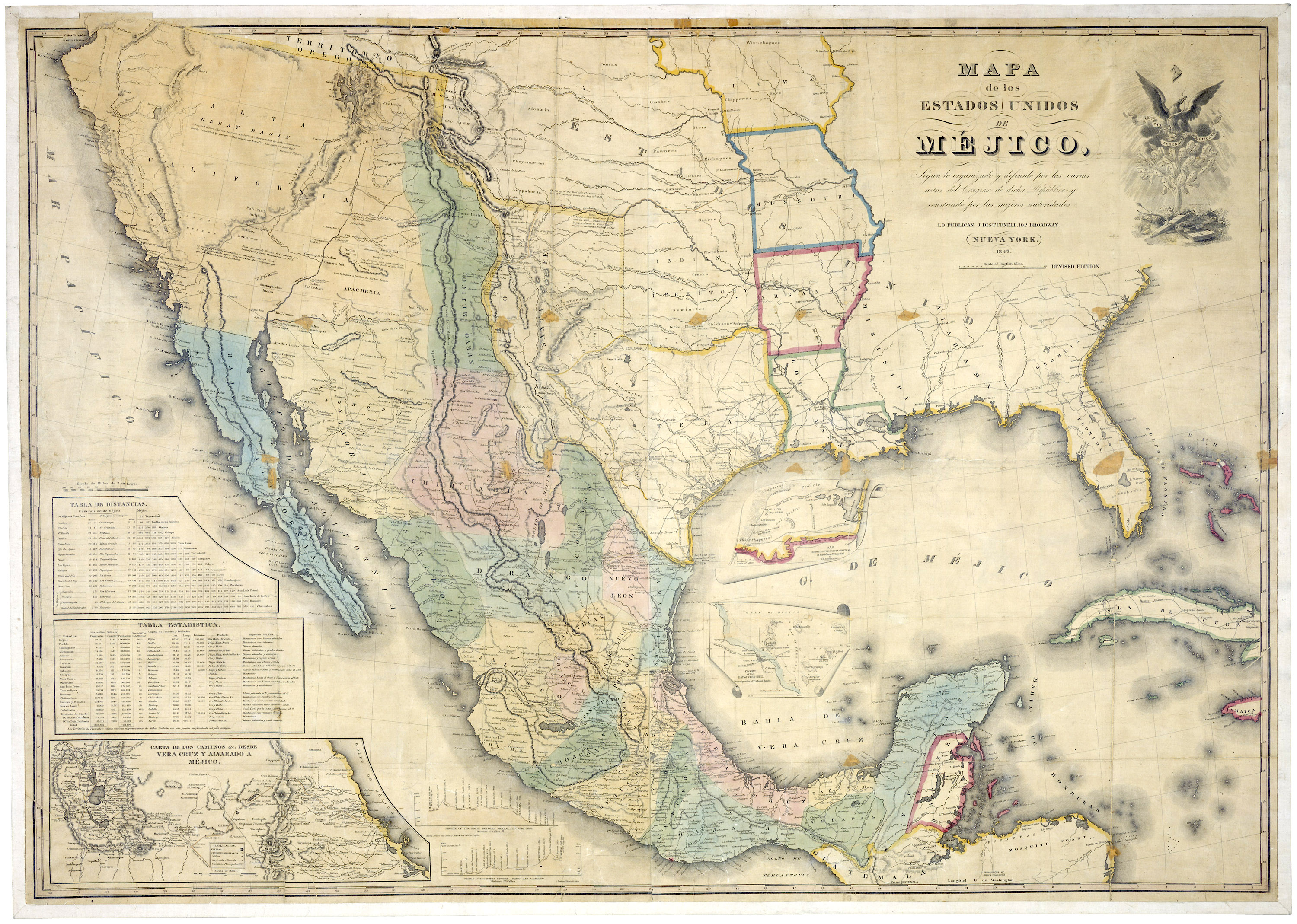

The war between the United States and Mexico lasted two years. The U.S. military attacked and occupied major cities, starting at the periphery of the country and eventually moving forces deeper inland and capturing the capital, Mexico City. The war introduced American violence and colonialism into the lives of Mexican people and was ended by the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. In this Treaty, Mexico ceded the land that now comprises the western United States, including all of California, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming. Territory boundaries in Mexico prior to the US-Mexico War are displayed in Figure 4.2.1. Prior to the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo in 1848, the territorial boundaries in the western United States and northern Mexico were significantly different from the present-day borders. The region was largely under Mexican control and included territories such as Alta California (present-day California), Nuevo México (present-day New Mexico), Tejas (present-day Texas), and parts of Arizona, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming. The border between Mexico and the United States was not clearly defined, and there were ongoing disputes and conflicts over the control of these territories.

Figure 4.2.1: “Mapa de los Estados Unidos de Méjico” by John Disturnell, Wikimedia Commons is in the Public Domain, CC0.

At the end of the 19th century, the United States furthered its imperialist military aggression during the Spanish-American War, which occurred during the spring and summer of 1898. The Spanish government’s hold on its colonies in the Caribbean and Pacific Ocean was weakened by internal politics and growing resistance among the peoples living under colonial rule. The war began in Cuba, with the U.S. supporting the Cuban dissidents who were asserting their independence from Spain. The United States mobilized its Navy against the Spanish, however, this did not lead to independence for Cubans. Instead, Cuba was taken under U.S. control for a period of time.

The war between the U.S. and Spain also included Puerto Rico, which was converted from the Spanish colonizers to become a U.S. territory. And the war extended to the Pacific Ocean, with the U.S. taking over colonial control of the Philippines and capturing the territory of Guam. In all of these locations, including the Caribbean, the Spanish-American War created a new relationship of migration between the mainland U.S. and the peoples living in the Caribbean islands. By the 20th century, tens of thousands of Cuban and Puerto Rican migrants had made their homes in the mainland United States.

At the same time, the social and cultural upheaval in Mexico led to the Mexican Revolution in 1910. This revolution elevated the political ideology Indigenismo which emphasizes celebrating Indigenous cultures and the Indigenous peoples are often the foundation of contemporary Mexican culture, politics, and society. Indigenous Leaders like Emiliano Zapata led the 1910 revolution calling for land reform (i.e., El Plan de Ayala) to redistribute land to the working class and break up the control and domination by the landowning elite (hacienderos). Zapata’s Indigenous tribal community in Puebla was deeply tied to land and communal corn traditions. He actually carried the land grants of his tribe. This personal experience informed his commitment to fight for a degree of sovereignty.

Beyond economic concerns, the ideology of Indigenismo was also championed and represented by cultural figures like Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. The recognition of cultural value led the post-revolutionary Mexican government, like Lazaro Cardenas’ administration to support bilingual education in Spanish and Indigenous languages. Cardenas’ commitment to Indigenous tribal communities throughout Mexico, led to some threats on his life. At one point the Indigenous people of Janitzio, Michocan, had to hide and protect his life for a period. Anti-Indian and racist sentiments of the cientificos (eugenics) of the 1940s attacked policy and efforts benefiting Indigenous people of Mexico. In many ways, Indigenous groups have cultivated energy and support to carry on their heritage by teaching traditional customs and practices in the face of threat and violence.19

In addition to the conditions in the “homeland” in the 20th century, the dynamics of U.S. Imperialism and militarism also negatively impacted the lives and migration patterns of Indigenous peoples in Latin America. Throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, the United States government directly and indirectly caused widespread political instability and supported the overthrow of standing governments throughout South and Central America, including Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, and Paraguay.

These actions were sponsored as part of the Cold War and politicians justified them by highlighting the antagonism between the U.S. and Communist countries, especially the Soviet Union and China. In the process, many Indigenous communities living in Latin America were subjected to violence, political corruption, and economic devastation. This led some Indigenous and mestizo groups to migrate to the United States, including entire communities and networks who brought with them Indigenous traditions of health and healing, languages, and customs of cultural wealth that they nurtured and passed on in their new homes. As a result, many communities in cities such as Los Angeles, Oxnard, Fresno, Bakersfield, and Santa Maria in California have substantial populations of Indigenous migrants from Mexico and Central America. They have created organizations of support as well, such as the Frente and others.

Footnotes

16 Douglas S. Massey and Magaly R. Sanchez, Brokered Boundaries: Immigrant Identity in Anti-Immigrant Times (New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation, 2010).

17 Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza, 1st ed. (San Francisco, CA: Aunt Lute Books, 1987); Guillermo Bonfil Batalla and Phillip A. Dennis, México Profundo (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1996); Jack Forbes, Aztecas Del Norte: the Chicanos of Aztlan (Robbinsdale, MN: Fawcett Publications, 1973).

18 Osuna, Steven. “Securing Manifest Destiny.” Journal of World-Systems Research 27, no. 1 (2021): 12–34, https://doi.org/10.5195/jwsr.2021.1023.

19 José Antonio Flores Farfán, “Keeping the Fire Alive: A Decade of Language Revitalization in Mexico,” De Gruyter Mouton 2011, no. 212 (2011): 189–209, https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.2011.052.