4.1: Concepts for Understanding Chicanx and Latinx Indigeneities

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 138202

- Mario Alberto Viveros Espinoza-Kulick & Melissa Moreno

- ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Core Definitions: Chicanx and Latinx Indigeneities

Indigeneity is a broad term that refers to a sense of belonging and ongoing ties among people from a shared homeland that originated before colonization. It is essential to understand the distinctions between Chicanx, Xicanx, Indigenous Latinx, and Latinx Indigenites. Indigenous Chicanx is a self-defined identity category signifying Indigeneity and awareness of their historical roots in this hemisphere, including Anahuac (Mesoamerica). Xicanx is a preferred identity term among some Chicanxs involved in Indigenous movements. “Chi” produces the same sound as “Xi,” but “Chi” is the Spanishpronunciation, and “Xi” is the Indigenous one.

Indigenous Latinx is an umbrella term for Indigenous migrants to the United States from South and Central America, the Caribbean, and Mexico (for example, Maya, Mixteco, Purépecha, Taino, Zapoteco, etc.). They are members of Indigenous pueblos or nations with traditional languages, customs, responsibilities to tribal communities, sensibilities, and dispositions. These identity labels were first introduced in Section 2.1: Defining Latinx Demographics.

To understand the lived experience of Indigenous Latinx peoples examined in this chapter, we rely on the work of Maylei Blackwell, Boj Lopez, and Luis Urrieta, who define Critical Latinx Indigeneities (CLI) as an analytic framework that addresses how Indigeneity is produced differentially by multiple colonialities present on Indigenous land, where different Indigenous diasporas exist in a shared space and is used to “critique enduring colonial logics and practices that operate from different localities of power as well as the physical, social, cultural, economic, and psychological violence that often targets Indigenous Latinx peoples, including forms of state and police violence, cultural appropriation, economic exploitation, gender violence, social exclusion, and psychological abuse.”1 CLI refuses the ways migration scholars overlook the ‘‘receiving countries’’ as Indigenous territories and nations. Thus, Critical Latinx Indigeneities works against the erasure of the Indigenous People. CLI examines mobility as a global Indigenous process of displacement and considers the shifts in racial formations and how Indigenous people are racialized differently across and between different settler states.

This perspective challenges Chicanx and Latinx studies to uproot ideologies in broader society, especially as they are reproduced through narrow definitions of Latinidad, as introduced in Section 2.1: Defining Latinx Demographics. For instance, Lopez and Urrieta say that the ideology of Indigenismo deployed during the Chicano movement is an “Aztec-centric celebration of the Indigenous past of the nation, which often serves to erase the present and future of the sixty-three Indigenous pueblos of Mexico” and the millions of Indigenous peoples living around the world.2 Others, like Tomas Perez, Jennie Luna, and Susy Zepeda, dispute that Indigenismo is only tied to Aztec culture and instead consider Indigenismo as promoting the various Indigenous pueblos for a growing sense of empowerment. This was observed in the case of Mexican President Larezo Cardenas when he provided institutional support to promote the culture, art, and history of many Indigenous Mexican tribes during his administration, which was not limited to Mexica Aztec. The various approaches to Indigenous identity are the subject of inquiry for Indigenous Chicanx and Latinx scholars.

Organization Spotlight: Chicanx and Latinx Indigenous Scholars

The Indigenous Peoples/Indigenous Knowledges Caucus has been a part of the National Association for Chicana and Chicano Studies (NACCS) since the mid-1990s and was formed with much struggle to recognize Indigenous roots. The caucus was established in response to the Zapatista uprising and Indigenous social movements, reminding the world of the presence of Indigenous people in the Americas. Participating scholars have contributed to scholarship for understanding Chicanx and Latinx Indigeneities in relationship to identity, foodways, land displacement, social movements, and futurities across borders. It was founded by Roberto Cintli Rodríguez, Jennie Luna, Roberto Hernández, Patrisia Gonzales, Gabriel Estrada, and Steve Casanova, and then led by Ernesto Tlahuitollini Colín, Robert Muñoz, Devon Peña, Melissa Moreno, Susy Zepeda, and others. Some caucus members are displayed in Figure 4.1.1 at a NACCS conference.

Figure 4.1.1: “Indigenous Peoples/Indigenous Knowledge Members” by Melissa Moreno, Author is licensed CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Indigenous Roots in Chicanx and Latinx Communities

Tienes el nopal en la frente (You have the cactus on your forehead) – dicho

This common and harmful saying means you are Indigenous or “look” Indigenous but are attempting to hide it. It is often used to refer to a self-hating person who appears to “clearly” look Indigenous but refuses to self-identify as Indigenous or with their Indigenous roots in any way. It is a saying that is commonly known among members of Indigenous Chicanx and Latinx communities. The common nature of this saying identifies how anti-Indigneous sentiments are part of sustained socio-cultural assumptions.

Like race and ethnicity, a sense of Indigeneity is constructed through cultural norms, shared group formations, communities, institutions, and families. Indigeneity is also often recognized and policed through phenotype, with individuals with darker skin and features associated with local Indigenous peoples being more likely to be visibly associated with stereotypes and cultural scripts about Indigenous people. However, Indigeneity is also constructed through systems of sovereignty, traditional knowledge, mutual recognition, and intergenerational kinship.

Indigenous peoples maintain and promote traditional languages, knowledge, and customs into the contemporary era. In the lands referred to as North America and Latin America, the Indigenous peoples have used names like Isla Tortuga / Turtle Island, referring to the North American continent; Abya Yala, referring to southern Mexico and Central America; and Pachamama, referring to South America. Indigenous people are also an active part of the culture, politics, and history of island societies in the Caribbean, such as the Arawak-speaking Taino people. These are regional solidarities that demonstrate the interconnected and globally conscious perspectives embedded in Indigenous communities.

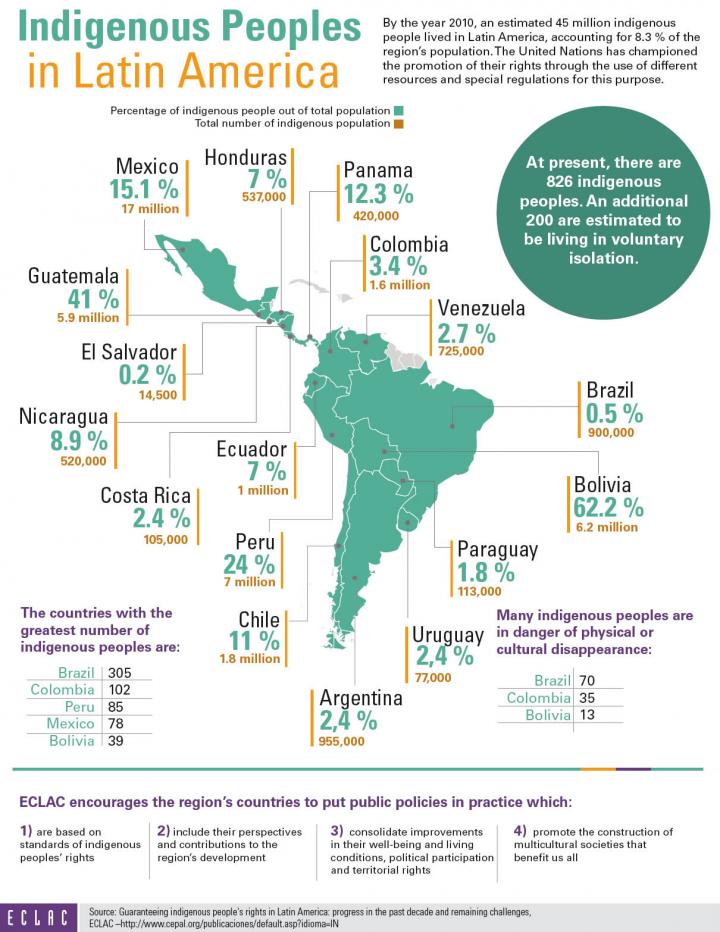

In Figure 4.1.2, a visual representation is displayed with the percentage of Indigenous people living in Latin American countries today, which totals 46 million across the region and ranges from 0.2% in El Salvador to 62.2% in Bolivia. Guatemala follows this at 41%, Peru at 24%, and Mexico at 15.1%. There are over 800 recognized Indigenous groups in Latin America, with the most significant number of distinct Indigenous peoples residing in Brazil, with over 300 different Indigenous peoples represented. Scholars also estimate that 200 or more groups operate actively but do not seek state or federal recognition.

The labels on the chart read: Indigenous Peoples in Latin America. By the year 2010, an estimated 45 million Indigenous people lived in Latin America, accounting for 8.3 % of the region’s population. The United Nations has championed the promotion of their rights by using different resources and special regulations for this purpose. At present, there are 826 Indigenous peoples. An additional 200 are estimated to be living in voluntary isolation.

In the chart, the countries are labeled by their name, percentage of Indigenous people out of the total population, and Total number of Indigenous population. They are Mexico, 15.1%, 17 million, Honduras 7%, 537,000, Panama 12.3%, 420,000, Colombia, 3.4%, 1.6 million, Venezuela, 2.7% 725,000, Brazil, 0.5%, 900,000, Bolivia, 62.2%, 6.2 million, Paraguay, 1.8%, 113,000, Uruguay, 2.4%, 77,000, Argentina, 2.4%, 955,000, Chile, 11%, 1.8 million, Peru, 24%, 7 million, Ecuador, 7%, 1 million, Costa Rica, 2.4%, 105,000, Nicaragua, 8.9%, 520,000, El Salvador, 0.2%, 14,500, Guatemala, 41%, 5.9 million.

Additionally, the captions included read: “The countries with the greatest number of Indigenous peoples are: Brazil, Colombia, 102, Peru 85, Mexico 78, Bolivia, 39.” and “Many Indigenous peoples are in danger of physical or cultural disappearance: Brazil, 70, Colombia, 35, Bolivia, 13.”

And the chart is summarized with the text, “ECLAC encourages the region’s countries to put public policies in practice which: 1) are based on standards of Indigenous people’s rights, 2) include their perspectives and contributions to the region’s development, 3) consolidate improvements in their well-being and living conditions, political participation and territorial rights, 4) promote the construction of multicultural societies that benefit us all.”

Indigenous Identities: Terminology and Definitions

Various creation stories are associated with distinct Indigenous peoples and nations and tribes of the Western Hemisphere, reflecting the diversity of the land and peoples. Some peoples whose homelands are now occupied by the United States include peoples the Haudenosaunee (Peoples of the Longhouse, also known as the Six Nations), Diné (also known as Navajo), Istichata (also known as Muskogee or Creek), and Siksikaitsitapi (also known as Blackfoot). In the lands now occupied by Latin America and the Caribbean, this includes groups like the Mexica Aztec Nation, Maya, Zapotec, Purépecha, Mixteco, Mapuche Peoples, Guarani Peoples, and many more across the Southwest, Southeast, Caribbean Basin, Amazon Basin. Indigenous people have distinct names and histories, which include contact, trade, conflict, and more. There are differences and diversity among these Indigenous groups, including traditions, language, religion, political organization, and more.3 However, despite these differences, Indigenous groups across the western hemisphere share the experience of various European invasions and colonization, and resisting and adapting to preserve culture, heritage, and identity.4

As a label, the word Indigenous is “used to describe peoples who existed before colonization and can be used to describe the Indigenous peoples of the Americas.”5 Always use the capital I: “Indigenous” to designate the term as a proper noun. By contrast, the word Indian by itself “connotes the history of settlers perpetuating genocide … While there are many individuals who use the term “Indian” to describe themselves, particularly when among their own in-group, it is often seen as offensive for non-Native individuals to use this term.”6 “The terms “American Indian,” “Native American,” “First Nations,” or simply “Native” are seen as more respectful.”7 Specifically, American Indian and Native American refer to Indigenous peoples of the lands currently occupied by the United States. First Nations is most frequently used by Indigenous people in Canada. Many individuals and communities primarily associate their identity with a specific tribal group or nation, like Chumash, Salinan, Purépecha, or Mixteco, rather than a general category.

For Chicanxs, in the 1960s, Aztlán was considered the name of a homeland in the area now known as the Greater Southwest in the United States. The claim to the Greater Southwest by Chicanxs in the 1960s is troubling because it overlooks the past and present existence of Native tribal nations living in the regions in these areas, who were colonized by the Spanish before becoming part of Mexico, and then the United States. The idea that Chicanxs had a rightful claim to the land is contradicted by the Nahua paradigm, which states that the meaning of Aztlán is not a physical homeland but rather a body of water that needs stewardship, from which ancestors of Chicanxs today migrated. This emphasizes the liberatory and transformative potential embedded in the idea of Aztlán, which is focused on antiracism, self-empowerment, and solidarity among Indigenous peoples. As well, many individuals and communities can trace their lineage to both Indigenous Latinx and Native American tribes, who had regular contact, trade, and cultural exchange in the region for centuries.

Historical Spotlight: Last Message on Education (August 12, 1521)

According to oral tradition, this is the last message by the Governing Council of Mexico Tenochtitlan, given by Cuauhtémoc as his last act of government on August 12, 1521. The message is about the importance of Indigenous parents teaching children traditions in the home, even during an invasion.

Our Sun has gone down

Our Sun has hidden its face

and has left us in complete darkness

But we know it will return again

that it will rise again

to light us anew

But while it is there in

the Mansion of Silence

Very soon will we join together and embrace each other

and in the very center of our being hide

all that

our hearts love

and we know is the Great Treasure.

We will destroy all of our temples to the Principal Creator,

our schools, our sacred ball game

our youth centers

our houses of song and play

Our streets will remain abandoned

Our homes will enclose us

until our New Sun rises.

Most honorable fathers and mothers,

may you never forget to guide your young

and teach your children while you live

how good it has been until now our beloved Anahuac

sheltered and protected our destiny

and for our great respect and good behavior

confirmed by our ancestors

and our parents enthusiastically received

and seeded in our being.

Now we will instruct our children

how good it will be, they will raise themselves up

and gain strength

and how good it will be to achieve their great destiny

in this, our beloved motherland of Anahuac.

Mestizaje and the Intersection of Indigeneity and Race

Stories of heritage among Chicanxs and Indigenous Latinxs vary on their past and present ties to their homelands. Mestizas/os/xs are a diverse population that has a combination of mixed heritage, often including Indigenous lineage, along with a combination of African and/or European backgrounds. Across these diverse groups, some have experienced contemporary forced acculturation, and others have been taught to believe they can assimilate and be invested in the dominant Spanish or Anglo-American cultural ways. The investment in whiteness is sometimes experienced through colorism when children are born, as they may be referred to as being a güerita/o or morenita/o if they have light or dark skin. Children’s light skin may be celebrated guided by the belief that they may eventually pass as white, which leads to identity conflict and pressure throughout development. Even the term “mestiza” or “mestizo” is sometimes used to assert a hierarchy between individuals of mixed heritage compared to Indigenous peoples with no Europaean (or African) heritage.

The idea of mestizaje, or mixed-race identity, emphasizes the multiple lineages that not only shape individual identity, but also the communities, cultures, languages, and traditions that we practice. José Vasconcelos Calderón called mestizos la raza cosmica (“the cosmic race”). However, an overemphasis on the mixing of various groups in Latin America can be used to create a false sense of equality that is not reflected in the actual conditions of racialized groups in Latin America, the United States, and Canada. In particular, Mexico and Brazil have both promoted a sense of national unity that attempts to erase differences based on race, color, and Indigeneity.8 For communities experiencing the effects of inter-generational oppression, segregation, and exploitation, the idea that all ethnic differences have fused in a post-racial society erases the realities of inequity and the importance of advocates calling for justice. For Indigenous peoples, reductive deployments of ethnic categorization can disrupt attempts for collective liberation.9

Marginalization continues through everyday stereotypes and myths about Indigenous people taught in various institutions, such as schools, mass media, and policy. As an example of anti-Indigenous oppression among Chicanx and Latinx people, we may hear pejorative terms like “India Maria” and “Oaxaquita,” signifying a connotation of inferiority. Community responsive efforts, like in Ventura California, have included the “No me llames Oaxaquita” campaign, which translates into “do not call me little Oxacca.” This effort created greater awareness about how this harmful term can negatively impact young people and their communities, motivating people to question their own biases and assumptions. Social movements have always been important for responding to the marginalization and direct threats to the lives of Indigenous peoples. Movement mobilization includes calling for sovereignty, treaty rights, resistance to Columbus Day and triumphalist narratives in history, stopping environmental destruction, water rights, cultural revitalization, land acknowledgment, and more. A land acknowledgment is a formal statement recognizing and respecting Indigenous Peoples as traditional stewards of the land as well as the historical relationship between Indigenous Peoples and their traditional territories.

Latinidad has also been critiqued for the ways that it calls for an overriding unity between all Latinx, Latina, and Latino people. These generalizations tend to benefit the most privileged within this group, including cisgender, heterosexual, male, English-speaking, light-skinned or white, citizen Latinos. For this reason, some groups who are multiply marginalized within the Latinx community have called against using this term, or qualifying it.10 Others have modified the term, including through the label, Afro-Latinx, which describes people from Latin America of African descent. For a refresher on Latinidad and Afro-Latinidad, you can return to Section 2.2: (Re)constructing Latinidades.

The histories and identities of Afro-descendant people and Indigenous peoples in the Americas have been interacting and intertwined for centuries. For example, the Garifuna people are of mixed African and Indigenous heritage from the island called St. Vincent. Members and descendants of this group exist across Central America, the Caribbean, and the United States, and are just one example of the strength and pride that has been built through solidarity with African and Indigenous heritage.

Afro-Latinxs are more likely to experience discrimination and policing in the United States than other Latinxs,11 and also more likely to raise these issues within Latinx communities more broadly.12 Within Latinx communities, dynamics of racism and colorism work to silence Afro-Latinx voices and discourage inclusive participation. Racial categorization in places like Brazil tends to be closely layered with colorism, leading to vastly different experiences of racial norms and consequences, even within biological families, based on one’s physical presentation of race.13

In the United States, self-identified Afro-Latinxs make up nearly 25% of the total Hispanic population.14 This suggests that the concerns of Afro-Latinx people are more central to both Black and Latinx cultures than is typically represented in popular media or social movements. For example, Black feminism often credits the development of major theoretical traditions like intersectionality to African-American women in the United States. However, when considering transnational Black communities, there have been theoretical and conceptual developments in places like Brazil that serve as roots of contemporary intersectional feminist movements. Recognizing these mutual sources of inspiration and activist mobilization is an opportunity for transnational coalitions and mutual learning. For example, Angela Davis has made a practice of collaborating with Black feminist leaders in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, such as Preta Ferriera, Lélia Gonzalez, and Marielle Franco.

The formal categorization of individuals into sub-categories by race was constructed by the Spanish empire in the Americas through the system of casta. Casta sorted people based on their heritage, religion, property ownership, occupation, race, color, place, and legitimacy of birth. A painting of the casta designations can be found in Figure 4.3 displays sixteen different designations organized hierarchically, with Spanish descendant (Español or Española) individuals ranked at the highest positions and those with Black and Indigenous ancestry ranked at the bottom. Note that these are historical terms and are not positive identity labels used in contemporary society. The categories displayed in the painting are included in the following list:

- Español con India, Mestizo

- Mestizo con Española, Castizo

- Castizo con Española, Español

- Español con Mora, Mulato

- Mulato con Española, Morisca

- Morisco con Española, Chino

- Chino con India, Salta atrás

- Salta atras con Mulata, Lobo

- Lobo con China, Gíbaro (Jíbaro)

- Gíbaro con Mulata, Albarazado

- Albarazado con Negra, Cambujo

- Cambujo con India, Sambiaga (Zambiaga)

- Sambiago con Loba, Calpamulato

- Calpamulto con Cambuja, Tente en el aire

- Tente en el aire con Mulata, No te entiendo

- No te entiendo con India, Torna atrás.

Figure 4.1.3: “Las castas” by Museo Nacional del Virreinato, Tepotzotlán, Mexico, Wikimedia Commons is in the Public Domain, CC0.

While the hierarchies created by Spanish colonizers and other European groups advancing white supremacy and settler-colonialism still influence social standing today, there are many active groups in social movements, politics, research, and education who are working to cultivate a sense of pride, community, and positive identity among Afro-Latinxs. You can learn more about these topics in Chapter 1: Foundations and Contexts. In Mexico, there is one of the largest Afro-Latinx populations. In 2020, a survey identified over 2.5 million Mexican residents who identify as Afromexican.15 As an optional exploration, you can learn more about some of the most recent research and scholarly books on the topic of Multiculturalism, Afro-Descendent Activism, and Ethnoracial Law and Policy in Latin America by visiting the Latin American Research Review website.

Footnotes

1 Blackwell, Maylei, Floridalma Boj Lopez, and Luis Urrieta. “Special Issue: Critical Latinx Indigeneities.” Latino Studies 15, no. 2 (July 1, 2017): 126–37. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41276-017-0064-0.

2 Blackwell, Boj Lopez, and Urrieta, 131.

3 M. Bianet Castellanos, Lourdes Gutiérrez Nájera, and Arturo J. Aldama, eds., Comparative Indigeneities of the Américas: Toward a Hemispheric Approach (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2012), https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1kz4hbt.

4 Miléna Santoro and Erick D. Langer, Hemispheric Indigeneities: Native Identity and Agency in Mesoamerica, the Andes, and Canada (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2 018), https://muse.jhu.edu/book/62740.

5 Lori Kido Lopez, ed., Race and Media: Critical Approaches (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2020), ix.

8 Edward Telles, Pigmentocracies: Ethnicity, Race, and Color in Latin America, 1st ed. (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

9 Gabriela Kovats Sánchez, “‘If We Don’t Do It, Nobody Is Going to Talk About It’: Indigenous Students Disrupting Latinidad at Hispanic-Serving Institutions,” AERA Open 7 (January 1, 2021): 1-13, https://doi.org/10.1177/23328584211059194.

10 Tatiana Flores, “‘Latinidad Is Cancelled’: Confronting an Anti-Black Construct,” Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture 3, no. 3 (July 1, 2021): 58–79, https://doi.org/10.1525/lavc.2021.3.3.58.

11 Luis Noe-Bustamante, Ana Gonzalez-Barrera, Khadijah Edwards, Lauren Mora, and Mark Hugo Lopez, “Majority of Latinos Say Skin Color Impacts Opportunity in America and Shapes Daily Life,” Pew Research Center’s Hispanic Trends Project (blog), November 4, 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2021/11/04/majority-of-latinos-say-skin-color-impacts-opportunity-in-america-and-shapes-daily-life/.

12 Ana Gonzalez-Barrera, “About 6 Million U.S. Adults Identify as Afro-Latino,” Pew Research Center (blog), accessed October 18, 2022, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/05/02/about-6-million-u-s-adults-identify-as-afro-latino/.

14 Gonzalez-Barrera, “About 6 Million U.S. Adults Identify as Afro-Latino.”

15 Jazmin Aguilar Rangel, “Infographic: Afrodescendants in Mexico” (Wilson Center, July 29, 2022), https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/infographic-afrodescendants-mexico.