5.1: The Roots and Routes of Chicana/Latina Feminisms

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 138206

- Amber Rose González

- ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

A Rising Ethnic Feminist Consciousness

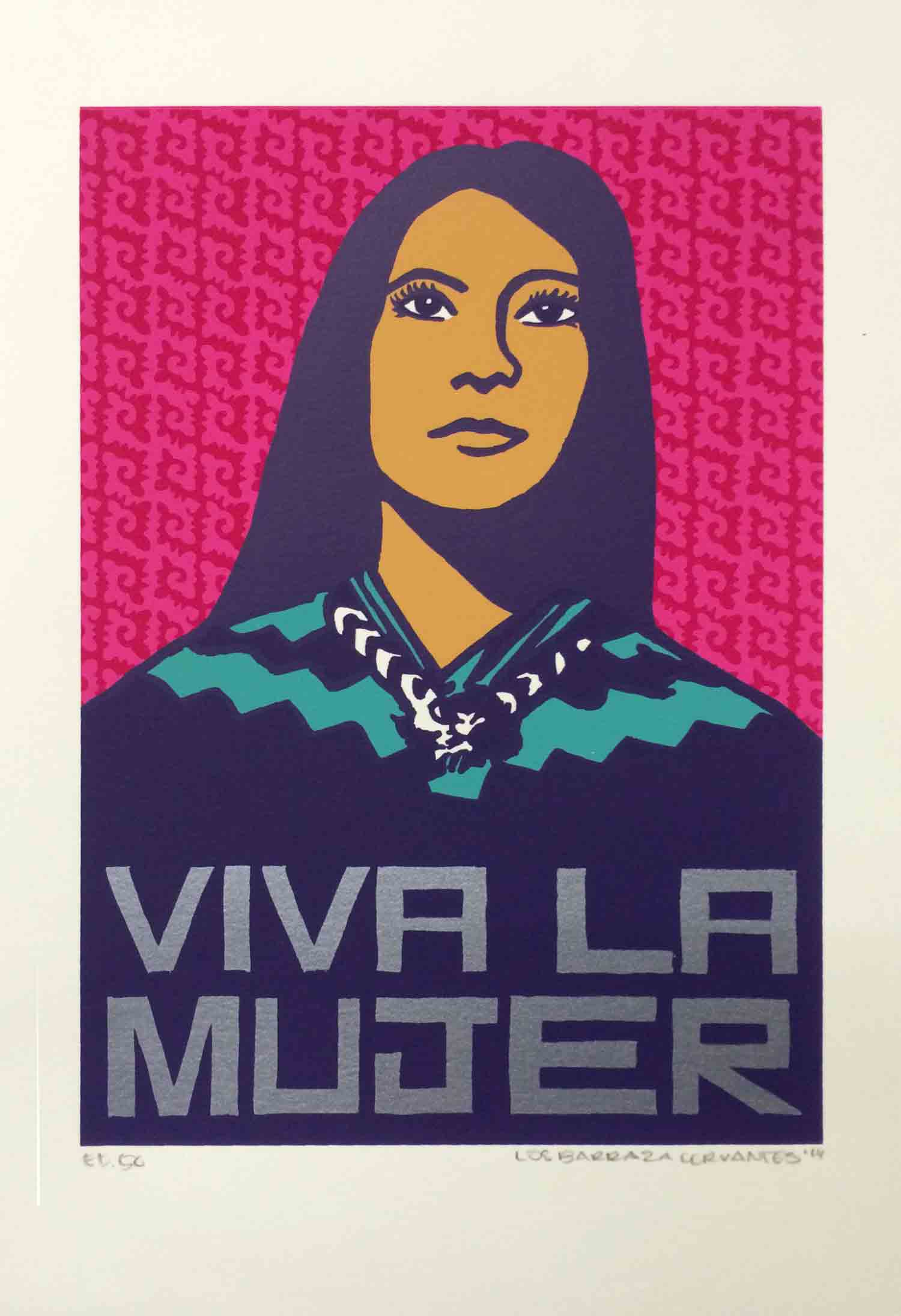

The emergence of what we now understand as Chicana/Latina feminisms can be traced back to ethnic nationalist movements of the late 1960s and early 1970s. As Chicana/o/xs and Puerto Ricans challenged racism and economic oppression across the U.S., women faced an additional battle––sexism, that is, discrimination or devaluation based on their sex or gender. Through their activism, writing, and visual and performance art, Chicana/Latina feminists brought to light the ways that patriarchy unevenly structured gender roles in their intimate relationships, within their organizations, movements, and in U.S. institutions. As noted in Chapter 7: Social Movement Activity, various struggles with different leaders, agendas, organizational philosophies, strategies, and tactics, often regional in scope, collectively defined El Movimiento. Chicanas and Latinas were active within each movement and in every locale since the beginning, and they developed as cultural nationalists alongside their male counterparts who espoused ethnic pride and self-determination. As the women developed an ethnic and class consciousness, they also began to develop a feminist consciousness critical of machismo, as it was often referred to in their early writings. Despite their critiques, most feminists did not want to create a separate movement. Instead, they hoped that their perspectives and advocacy would transform and strengthen movement ideologies and agendas. In other words, “Chicana feminist thought reflected a historical struggle by women to overcome sexist oppression but still affirm a militant ethnic consciousness.”3 Figure 5.1.1 depicts a brown-skinned Xicana who has ethnic pride and a feminist consciousness, as suggested by the title, “Viva La Mujer.” The hot pink background suggests inner strength, love, and rebelliousness.

Chicana feminists organized regional and national conferences, seminars, workshops, caucuses, and consciousness-raising (CR) group meetings in the early 1970s that provided a collective space to develop their ideas and priorities.4 In the seminal manifesto “New Voice of La Raza: Chicanas Speak Out” produced in 1971, Argentinian-born socialist feminist Mirta Vidal points out how Chicana feminists were “beginning to challenge every social institution which contributes to and is responsible for their oppression, from inequality on the job to their role in the home. They are questioning ‘machismo,’ discrimination in education, the double standard, the role of the Catholic Church, and all the backward ideology designed to keep women subjugated.”5 Vidal and other feminist writers in the early 1970s argued that Chicanas were subjugated based on their race, as workers, and as women, naming this phenomenon triple oppression.6

As Chicana feminists worked to introduce their concerns into their respective movement spaces, they faced resistance from Chicanos and Chicana loyalists who believed that race and class oppression should be the primary agenda and that feminism was divisive to the movement.7 Historian Maylei Blackwell points out that the Chicano movement’s rejection of feminism was due to its reliance on a vendida logic, that is, “a silencing mechanism used against dissident Chicana activists” by labeling them as:

- Agabachas or agringadas (race traitors);

- Vendidas or malinchistas (sell-outs) dividing the movement from the primary struggle;

- Marimachas (sexual deviants or lesbians);

- Inauthentic/outside of/antagonistic to Chicano culture.8

Guided by the ideology of Chicanismo, those resistant to Chicana feminist concerns glorified la familia and rigid gender roles that expected women to bear children, care for the household, and be subordinate to their husbands.9 Men and women were also expected to maintain a gendered division of labor in the movement. Since women were disregarded as real political actors, they were expected to do things like cook, clean, and perform clerical work. Chicana feminists began calling attention to the fact that these gendered cultural expectations were first imposed by the colonial Catholic Church during the Spanish conquest and enforced through a dichotomy that constructed women as a ‘mujer buena’ or a ‘mujer mala,’ otherwise known as the virgin/whore complex.10 On one side of the dichotomy is marianismo, the deep reverence for La Virgen de Guadalupe who is valued as the subservient all-suffering virgin mother. On the other side is the Indigenous woman La Malinche, known for being Hernan Cortes’s concubine, translator, mediator, and fabled mother of the first mestizo. As a Native woman, she is characterized as sexually available, disposable, and condemned as a traitor for contributing to the downfall of the Aztec civilization. In modern times, these doctrines about Chicana womanhood reinforce patriarchy, obliging Chicanas to take on the contradictory roles of obedient wife and mother and to also be sexually available. But the lived reality of most Chicanas did not afford them the ability to be homemakers. Because many Chicanas were working class or lived in poverty and had limited access to educational opportunities, they were compelled to take on low-wage work outside of the home, typically in domestic service or the garment industry, in addition to their household obligations. Moreover, due to gender discrimination in the workplace, Chicanas tended to earn less than their Chicano counterparts.

Chicana lesbian feminists who sought to challenge homophobia in addition to sexism faced intense backlash and were often silenced. In the groundbreaking compilation Chicana Feminist Thought: The Basic Historical Writings (1997), feminist and immigration scholar Alma M. García points out that “in a political climate that viewed Chicana feminist ideology with suspicion and, often, disdain, Chicana feminist lesbians confronted even more strident political attacks.”11 However, as El Movimiento began to transform in the late 1970s and early 1980s, including the emergence of Chicano/a studies, the academic arm of the movement, Chicana lesbian feminist writing and cultural production flourished, further advancing Chicana feminist thought and activist priorities, which will be explored in Section 5.6: Activist Scholarship and Chicana and Latina Studies.

As El Movimiento was underway, so was the mainstream women’s movement, which sought to secure equal rights and access for women.12 Many Chicanas found the women’s movement agenda to be insufficient as it centered white middle-class and upper-class feminist perspectives and excluded considerations of race and class oppression. They found conventional white feminist views to be limited for focusing too narrowly on all men as the enemy, whereas Chicanas felt that colonization and structural oppression were the real issues. Not only did Chicanas speak out against sexism, but they also spoke out against racism and elitism in the women’s movement––what Angela Davis has called “bourgeois feminism.” Many Chicana feminists found that these experiences mirrored those of other women of color in the U.S., which in part, facilitated the building of strategic coalitions. Their goal was not to establish a unified position, but rather, to develop an ability to dialogue across lines of difference and come together to address important issues.

Developing a U.S. Third World Feminist Consciousness and Praxis

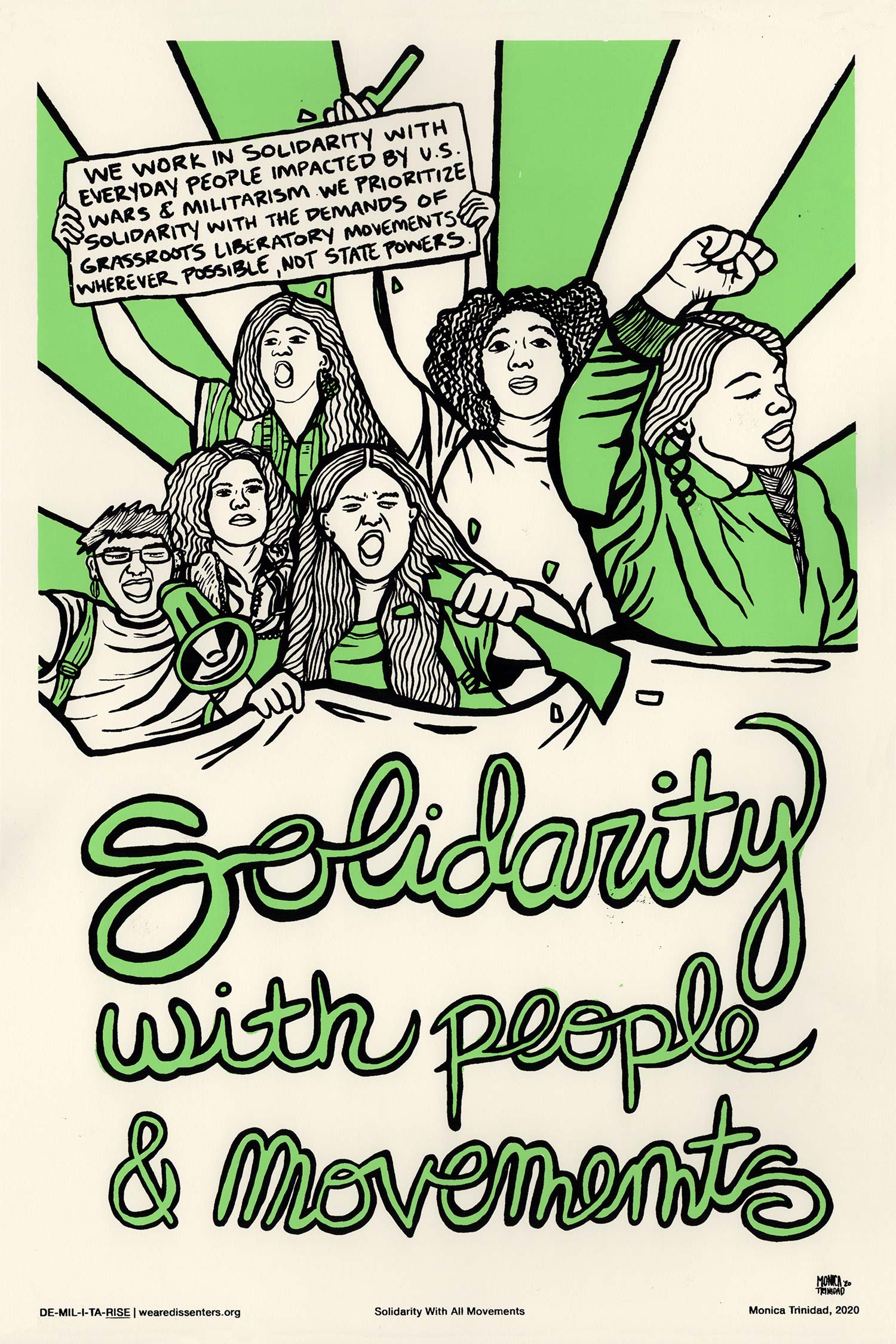

Since the late 1960s, Latinas have constructed a feminist standpoint not only in resistance to patriarchal ethnic nationalism and U.S. hegemonic feminism, but also in solidarity with an emerging U.S. Third World feminist consciousness informed by global decolonial and anticolonial movements. As they critiqued and attempted to dismantle interlocking systems of oppression through racially specific feminist projects, feminists of color in the U.S. created a new cross-racial political subjectivity and oppositional praxis, that is, putting theory into action, that linked various struggles for social justice. María Cotera argues, “Because Latina feminists (like other women of color feminists) understand feminism in relationship to other struggles for liberation and decolonization, their approach to ‘women’s liberation’ necessarily moves beyond gender, just as their commitment to end racism and colonialism moves beyond race and nation.”13 Figure 5.1.2, “Solidarity With All Movements,” demonstrates the throughline of this standpoint by illustrating the work of Dissenters, a contemporary youth-led national anti-militarism movement organization that prioritizes solidarity with other liberatory grassroots movements. The sign in the image says “We work in solidarity with everyday people impacted by U.S. wars and militarism. We prioritize solidarity with the demands of grassroots liberatory movements wherever possible, not state powers.” The caption in large bold letters reads “Solidarity with people and movements.”

Women of color developed new forms of consciousness characterized by critiques of capitalism, economic exploitation, imperialism, and war, grounded in international solidarity. Chicanas and Latinas in particular drew inspiration from 20th-century Latin American and Mexican feminisms and women’s revolutionary participation. They also developed their praxis by traveling to international conferences such as the Indochinese Women’s Conference in 1971 in Vancouver, Canada as part of the antiwar effort.14 Also instrumental in the development of a U.S. Third World feminist consciousness and praxis were the multiracial multi-issue print communities, such as those established through Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, founded in 1980 by Black and Chicana lesbian feminists. Kitchen Table published several seminal texts including This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, edited by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldá (1981), Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology by Barbara Smith (1983), I Am Your Sister: Black Women Organizing Across Sexualities by Audre Lorde (1985), Apartheid USA: Our Common Enemy, Our Common Cause: Freedom Organizing in the Eighties by Audre Lorde and Merle Woo (1985), and The Combahee River Collective Statement: Black Feminist Organizing in the Seventies and Eighties (1986).

Emerging Movements and Ongoing Activism

While Chicana and Latina feminists share some commonalities, like their respective movements, they too had divergent ideologies, agendas, and priorities. García points out how:

Chicana feminist thought evolved with several divergent, often competing, views. Chicana feminists confronted divisions based on social class, particularly the division between academic women and grass roots community women, sexual orientation, political strategies, political goals and objectives, the relationship between autonomous Chicana feminist organizations and white women’s feminist organizations, and their relationships with Chicano organizations and Chicano men in general.15

Likewise, Blackwell notes that as political subjects with multiple identities, women of color organizing often takes on the following features: “(1) multiple issues in one movement, (2) an intersectional understanding of power and oppression, and (3) the tendency to work in and between movements.”16 Due to the complex nature and scale of Chicana/Latina activism, it would be impossible to cover every cause that Chicana and Latina feminists have participated in since the late 1960s. Therefore, four predominant and interrelated issues have been selected and will be introduced in the following sections. These include economic justice, reproductive justice, cultural activism, and family dynamics.

Artivist Spotlight: Mujeres de Maiz

Founded in 1997 Mujeres de Maiz (MdM), or women of the corn, is an unapologetic Xicana-Indígena led spiritual artivist (artist-activist) organization and movement by and for women and feminists of color whose mission is “to bring together and empower diverse women and girls through the creation of community spaces that provide holistic wellness through education, programming, exhibition, and publishing.” Early on, founders and core members participated in the Encuentro Cultural Xicano Indígena por la Humanidad y Contra el Neo-liberalismo with the Indigenous Zapatista Mayan community of Oventic. As a result, Zapatista philosophy significantly influences their artivist praxis, particularly the emphasis on building alliances with exploited and marginalized communities around the world.

Every spring MdM publishes a new issue of Flor y Canto, their poetry and arts zine, which is released at the Live Art Show, an intercultural, intergenerational, multimedia event that combines elements of an art exhibit, live performances, and ritual ceremony featuring women of color musicians, dancers, visual artists, poets, actors, filmmakers, and spiritual healers. Other community events hosted by MdM include the mujer mercado, poetry night event, film screenings, women’s ceremonies such as the monthly Coyolxauhqui full moon circle, and workshops, held in person and virtually, with topics ranging from art making, creative writing, gardening, self-defense, and women’s health, often in collaboration with other feminist of color organizations and groups from the Eastside of Los Angeles such as Justice for my Sister, Af3irm, Hood Herbalism, and WE RISE LA, to name a few.17

Footnotes

3 Alma M. García, “Introduction,” in Chicana Feminist Thought: The Basic Historical Writings, ed. Alma M. García (New York: Routledge, 1997), 1.

4 One of the earliest Chicana workshops was held at the first National Youth Liberation Conference in 1969.

5 Mirta Vidal, “New Voice of La Raza: Chicanas Speak Out,” in Chicana Feminist Thought: The Basic Historical Writings, ed. Alma M. García (New York: Routledge, 1997), 21. The manifesto recognized the Plan de Aztlán but it took on additional concerns not addressed in El Plan producing resolutions on sex, marriage, and religion. It is important to note “While the Plan de Aztlán has retained its foundational status, the women’s document never entered the Chicano archive at all” (Pratt, “Yo Soy La Malinche,” 861).

6 U.S. Third-World, Puerto Rican, and Black feminists were simultaneously theorizing and organizing around the convergence of multiple systems of oppression, drawing on an intergenerational feminist lineage dating back hundreds of years. Review Elizabeth ‘Bettita’ Martínez, 500 Years of Chicana Women’s History/500 Años de la Mujer Chicana (New Brunswick: Rutgers, 2008).

7 Anna NietoGomez, “La Feminista,” in Chicana Feminist Thought: The Basic Historical Writings, ed. Alma M. García (New York: Routledge, 1997), 87-88.

8 Maylei Blackwell, ¡Chicana Power!: Contested Histories of Feminism in the Chicano Movement (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2011), 31.

9 This ideology can understood through the lens of compulsory heterosexuality, a concept coined by Adrienne Rich, which illuminates the societal assumption that all people are straight and will be sexually attracted to and reproduce with the ‘opposite’ sex. Under Spanish, Mexican, and U.S. patriarchy, the nuclear family has been constructed as the cornerstone of society and social reproduction. Review “Compulsory Heterosexuality” by Adrienne Rich and “Heteropatriarchy” by Andrea Smith.

10 Anna NietoGomez, “Chicana Feminism,” in Chicana Feminist Thought: The Basic Historical Writings, ed. Alma M. García (New York: Routledge, 1997), 57.

11 García, Chicana Feminist Thought, 7.

12 The mainstream women’s movement of the late 1960s and 1970s has been defined as expressing at least three distinct positions: liberal feminists who sought access to power and advanced social standing equal to men’s, radical feminists who viewed men as having access to power and responsible for women’s oppression, and liberation feminists who believed women’s oppression was one of many oppressions tied up in the economic system, which must be understood and transformed to end all oppressions (NietoGomez, “Chicana Feminism,” 55). In Feminism is for Everybody, bell hooks provides additional insight into divergent feminist activist modes, naming them revolutionary feminism, reformist feminism, and lifestyle feminism.

14 Dionne Espinoza, “La Raza in Canada: San Diego Chicana Activists, The Indichinese Women’s Conference of 1971, and Third World Womanism,” in Chicana Movidas: New Narratives of Activism and Feminism in the Movement Era, eds. Dionne Espinoza, María Eugenia Cotera, and Maylei Blackwell (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018), 261-275.

16 Blackwell, ¡Chicana Power!, 27.

17 Amber Rose González, “Todos Somos Mujeres de Maiz, An Introduction,” in Mujeres de Maiz en Movimiento: Spiritual ARTivism, Healing Justice, and Feminist Praxis, eds. Amber Rose González, Felicia Montes, and Nadia Zepeda (Forthcoming, Tucson: University of Arizona Press).