5.2: Fighting for Economic Justice

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 138207

- Amber Rose González

- ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Labor Organizing

Chicanas and Latinas have an extensive history of working to improve the material conditions of their communities through their participation as both rank-and-file workers and leaders in the ongoing labor movement powerfully emerging in the 20th century. These historical efforts are presented in eight and a half minutes in Video 5.2.1 "Latinas in the Labor Movement."18

Video: Latinas in the Labor Movement

Video 5.2.1: “Latinas in the Labor Movement.” Youtube, uploaded by TIME, January 28, 2021. Permissions: YouTube Terms of Service.

The fight for economic justice continued in May 1972 when 4,000 garment factory workers, predominantly Mexican American women, walked out of their jobs at Farah Manufacturing Company plants in Texas and Júarez, Mexico after six workers were illegally fired for union activity. In 1970 the majority of the workers voted to unionize with the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA) for higher wages, maternity leave, workplace safety, and an end to sexual harassment, but management refused to recognize their efforts. According to labor organizer and journalist Kim Kelly, “Immigrant women of color make up the bulk of the garment industry’s workforce, both in the U.S. and globally, and are forced to bear the brunt of its dangerous conditions, low pay, and high-volume output. Through decades of organizing, strikes, and knock-down, drag-out fights, they have worked to change that status quo and push back against an industry that devalues their humanity and their labor in equal measure.”19

The president of the company William ‘Willie’ Farah was a staunch anti-union employer who relied on Red Scare tactics in an attempt to denigrate and delegitimize union efforts by associating unionization with communism and firing union organizers, among other retaliatory union-busting tactics. The company went as far as running down strikers with their trucks and during the first week of the strike Farah management hired “private guards to harass the women on the picket line and menace them with unmuzzled dogs.”20

Strikers were protesting exploitative working conditions including having their already low wages docked if they did not meet increasing quotas, being denied bathroom access to meet the quotas, which caused bladder and kidney infections, poor ventilation that resulted in a variety of respiratory illnesses, and generally hazardous conditions.21 Because women did not have maternity leave and could not afford to go without pay, “women sometimes gave birth in the company clinic.”22 The racialized gendered oppression that Chicanas faced at Farah was also present within their union. Rank-and-file women workers often complained that the male leadership did not address their specific needs and demands as women. As the strike went on and their input ignored, women’s disappointment grew, leading some Farah workers in El Paso to form Unidad Para Siempre, a separate caucus that promoted the movement in their vision.

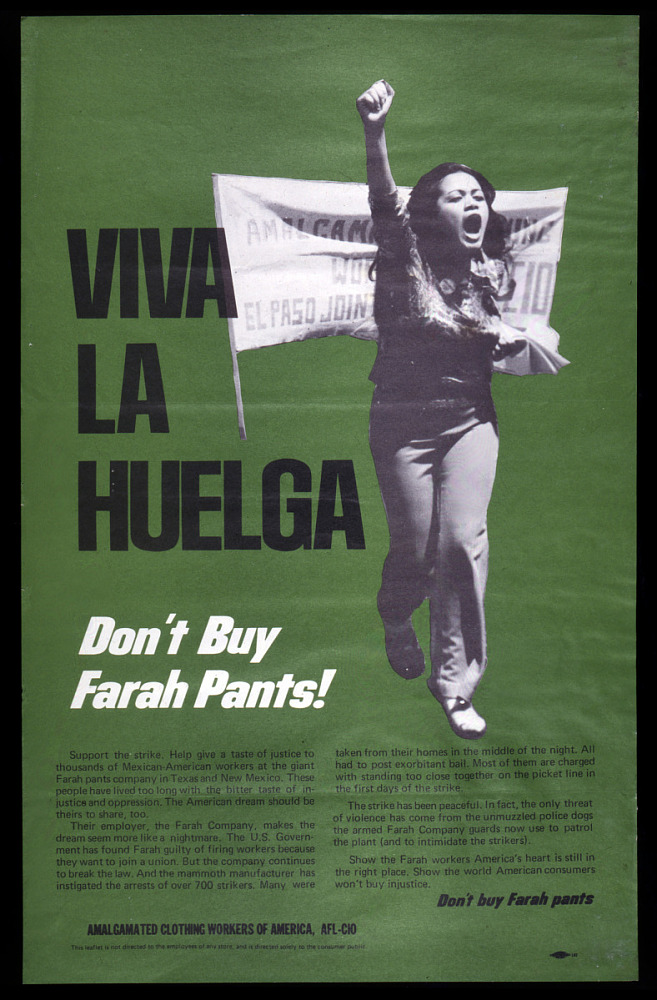

Despite these obstacles, the Chicana strikers persisted.22 With the support of religious leaders and major labor unions across the country, including the United Farm Workers, they called for a national boycott of Farah pants guided by the rallying cry, “Viva La Huelga––Don’t Buy Farah Pants!” The boycott poster, demonstrated in Figure 5.2.1, featured Rosa Flores from San Antonio, Texas, one of the first Farah workers to sign a union card and publicly announce her pro-union stance on the factory floor. The boycott transformed the local strike into a national issue, resulting in a $20 million decline in Farah’s annual revenue, putting immense pressure on the manufacturer.

The text on the poster reads, "Viva La Huelga. Don't Buy Farah Pants! Support the strike. Help give a taste of justice to thousands of Mexican-American workers at the giant Farah pants company in Texas and New Mexico. These people have lived too long with the bitter taste of injustice and oppression. The American dream should be theirs to share, too. Their employer, the Farah Company, makes the dream seem more like a nightmare. The U.S. Government has found Farah guilty of firing workers because they want to join a union. But the company continues to break the law. And the mammoth manufacturer has instigated the arrests of over 700 strikers. Many were taken from their homes in the middle of the night. All had to post exorbitant bail. Most of them are charged with standing too close together on the picket line in the first days of the strike. The strikers had been peaceful. In fact, the only threat of violence has come from the unmuzzled police dogs the armed Farah Company guards now use to patrol the plant (and to intimidate the strikers). Show the Farah workers America's heart is still in the right place. Show the world American consumers won't buy injustice. Don't buy Farah pants. Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, AFL-CIO."

After twenty-two months of striking and a successful national boycott, the strikers finally earned their right to unionize in 1974, becoming one of the first and only garment plants in the Southwest to be unionized.23 The new contract came with increased wages, health benefits, job security, and seniority rights. The material success was short-lived, however, as the 1970s marked the onset of deindustrialization with numerous U.S. manufacturing plants, including Farah, closing shop and moving production overseas and across the border to Mexico where labor rights and environmental laws were even more lax. The lasting effects of the strike came in the form of women’s empowerment.24 In interviews following the strike, Chicanas expressed that the movement emboldened them to take a more politically active role in their communities and to challenge repressive gender norms both at work and at home.25 The Chicana organizers of the Farah Manufacturing Strike contributed to the ongoing labor movement and unionization efforts that characterized the better part of the 20th century. Today, Latinas who work full time year-round earn 57 cents for every dollar earned by white, non-Hispanic men.26 The struggle for economic justice continues.

Welfare Rights

Another arena where Chicanas and Latinas were actively involved in economic justice efforts was the movement for welfare rights. Deindustrialization led to an economic downturn in postwar Los Angeles characterized by high unemployment and poverty rates, particularly experienced by women of color, many of whom had previously migrated to Southern California for employment opportunities during the WWII industrial boom. Demographic shifts and policy changes that made it easier to qualify for aid in the 1950s and 1960s led to an increase in African American and Mexican American welfare recipients, which “was met by a racist backlash against families of color, cuts to welfare budgets, and punitive disciplinary measures to control the behavior of poor mothers.”27 Discriminatory laws and policies were rationalized through depictions of Latinas, Native American women, and Black women in the media and public policy discourse as dependent on the government, abusing welfare aid, and sexually promiscuous (For more on this topic visit “The Backlash and Disinvestment in Public Education” in Section 8.3: Re-imagining Education in an Era of Revolt, 1955-1975). Women of color faced systemic denial of services and unconstitutional practices such as warrantless home searches, being “compelled to answer caseworkers’ intrusive questions about their sexuality and personal behavior,” pressure “to undergo sterilization or give up their babies for adoption,” and having their children placed into foster care, limiting their reproductive choices, personal autonomy, and human rights.28

Despite this demeaning treatment, welfare recipients fought back. The Los Angeles County Welfare Rights Organization (LAWRO) developed from the collaborative efforts of Mexican American and African American women in the 1950s whose efforts grew into a “multiracial coalition of neighborhood-based AFDC recipient groups” who fought against economic marginalization in the 1960s and 1970s.29 Many Welfare Rights Organizations formed across the nation and were brought together in June 1966 by the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO), of which Black and Puerto Rican women were instrumental, for the first national day of action for welfare rights. People marched in Washington D.C., Baltimore, and New York City, as well as in Los Angeles where Mexican American, Puerto Rican, African American, and white women and children demanded job training, quality jobs, childcare, and dignity for families on public assistance. The women of LAWRO, inspired by the broader civil rights struggles and power movements around them, provided know-your-rights workshops in the community, demanded a voice in welfare policy, provided social support for one another, and organized countywide campaigns and mass public demonstrations.

In Los Angeles, Chicanas and Black women organized separate but akin organizations in their respective neighborhoods and came together to form a countywide alliance of various independent WRO groups. They built coalitions around poverty, welfare, and motherhood, forging a common Brown-Black movement that honored racial and ethnic autonomy while enabling cross-racial solidarity. Chicanas were important activists and leaders from the beginning of the welfare rights movement, including Alicia Escalante, a poor single mother of five who founded the prominent East Los Angeles Welfare Rights Organization (ELAWRO) in 1967, later known as the Chicana Welfare Rights Organization (CWRO).

Activist Spotlight: Alicia Escalante

Alicia Escalante’s story is exceptional but not uncommon. Born and raised in the 1930s and 1940s in El Chamizal, a Mexican barrio in El Paso, Texas, Escalante grew up in poverty with her abusive father. As a youth, she fled to California to be with her mother where she witnessed the cruelty of the welfare and medical systems firsthand. These formative experiences, coupled with the fact that as a teenager she needed to work to sustain her household, shaped her political consciousness, leading her to become an advocate for her mother and later for herself and her own family as well as members of her community. Ecalente’s activism was rooted in an ethic of love and care for the people around her, eventually leading her to found the East Los Angeles Welfare Rights Organization in 1967 (later known as the Chicana Welfare Rights Organization) and La Causa de Los Pobres, the organization’s newspaper. Characterized by her growing empowerment and personal sense of agency, “Escalante and the [ELAWRO] challenged the status quo of the welfare system by providing informational services to recipients, representation during fair hearings (meetings to appeal decisions made by the welfare department), and direct engagement with the local and state bureaucracy to ensure that recipients rights were respected and upheld.”30 The organization ran workshops on welfare policies, advocated for welfare forms in Spanish and additional local offices staffed with bilingual Mexican American caseworkers, and worked for humane public policy at the county, state, and federal levels. While advocating for recipients in East Los Angeles, Escalante frequently collaborated with Black women activists Johnnie Tillmon and Catherine Jermany on countywide campaigns. Escalante was also involved in other facets of the Chicano Movement, supporting and participating in the East Los Angeles high school blowouts, the anti-war movement, and the Poor People’s Campaign in Washington D.C. A prolific writer and orator, Escalante demanded dignity for poor single Chicana mothers on welfare, a group relegated to the margins in both the Chicano movement and the welfare rights movement.31

Footnotes

18 Some notable 20th century labor organizers include Luisa Capetillo, Luisa Moreno, Emma Tenayuca, and Dolores Huerta, as well as the hundreds of women who participated in the cannery strikes in California and Texas and the miner’s strikes in New Mexico, documented in the work of Chicana historians Vicki L. Ruiz and Patricia Zavella and in the film Salt of the Earth, respectively.

19 Kim Kelly, “The Farah Manufacturing Strike Was Led By Chicana Activist Rosa Flores,” Teen Vogue, April 26, 2022.

20 Kelly, “Farah Manufacturing Strike.”

21 Kim Kelly, “The Garment Workers,” in Fight Like Hell: The Untold Story of American Labor (New York: One Signal Publishers, 2022), 37.

22 Jennifer R. Mata, “Farah Strike,” in Latino History and Culture, An Encyclopedia, eds. David J. Leonard and Carmen R. Lugo-Lugo (London: Routledge, 2010), 180.

23 Emily Honig, “Women at Farah Revisited: Political Mobilization and Its Aftermath among Chicana Workers in El Paso, Texas, 1972-1992,” Feminist Studies 22, no. 2 (July 1, 1996): 425–52, doi:10.2307/3178422.

24 Wins for social justice are typically not black and white and they are often impermanent. Progress is not linear––it is an ongoing negotiation of power and resistance requires creative maneuvering and persistent action.

25 Honig, “Women at Farah.” In the introduction to Las Obreras: Chicana Politics of Work and Family, Chicana historian Vicki L. Ruiz argues, “Women bring attitudes from home to the workplace and from work to home. Empowerment and conflict exist side by side as women struggle to rationalize and integrate wage earning with domestic responsibilities” (2000, 5).

26 “Latina Equal Pay Day 2022,” Equal Rights Advocates, accessed October 26, 2022.

27 Alejandra Marchevsky, “Forging a Brown-Black Movement: Chicana and African American Women Organizing for Welfare Rights in Los Angeles,” in Chicana Movidas: New Narratives of Activism and Feminism in the Movement Era, eds. Dionne Espinoza, María Eugenia Cotera, and Maylei Blackwell (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018), 231.

28 Marchevsky “Forging a Black-Brown Movement,” 232.

29 Marchevsky “Forging a Black-Brown Movement,” 228.

30 Rosie C. Bermudez, “La Causa de los Pobres: Alicia Escalante’s Lived Experiences of Poverty and the Struggle for Economic Justice,” in Chicana Movidas: New Narratives of Activism and Feminism in the Movement Era, eds. Dionne Espinoza, María Eugenia Cotera, and Maylei Blackwell (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018), 132.

31 For more review Alicia Escalante in the Chicana Por Mi Raza Archive.