8.3: Re-imagining Education in an Era of Revolt, 1955-1975

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 138278

- Lucha Arévalo

- ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Education for Liberation

Education has always been a central function of colonization and oppression, but when reclaimed by oppressed people it can be a key function for liberation struggles. As the struggle for civil rights continued into a new era of social change, it created opportunities for students, families, and activists to re-imagine their local schools and education in general. While today it may be easy to take for granted the existence of ethnic studies classes such as the one you are in, it is important to know that the field was created and sustained as a result of political pressure by social movements. Before the formation of ethnic studies, communities that were historically marginalized took education into their own hands, such as offering political education and presenting counter cultures, such as art, murals, teatro, and music to uphold values and norms contrary to mainstream society (Visit Chapter 10: Cultural Productions). These non-traditional forms of education are among the many ways that history is recorded, disseminated, and preserved.

The Chicano movement (Review Chapter 7: Social Movement Activity for a history of the Chicano movement), and other movements of the time, such as the antiwar and women’s rights movements, collectively are examples of different communities taking more militant approaches to generating political power. During these times, younger generations of Mexican Americans also redefined their identity to include radical political identities such as Chicana and Chicano that extended beyond their ethnicity and united in solidarity with peoples of the “third world” to create change (Review Chapter 1: Foundations and Contexts and Section 7.2: Chicanx and Latinx Civil Rights Activism). The education that occurred in and out of schools, ignited and sustained generations of activists working to transform their high schools, colleges, and universities. During this time, the struggle was no longer merely about access to education, but questioning the function and responsibility of educational institutions altogether.

Little School of the 400

The absence of effective schools to address the discrimination Mexican American children experienced, led to the formation of schools that were run by Mexican Americans. In 1957, one such school was spearheaded by LULAC. The Little School of the 400 (LS400) was a preschool program that was first created in Texas to teach Spanish-speaking children to be bilingual by teaching them 400 English words. These preschool classes would help children build their English vocabulary, giving them the academic confidence to succeed in school. The LS400 was an initiative to Americanize children of Mexican heritage, but unlike Americanization efforts led by whites, this school did not instill a sense of inferiority.36 Instead, it was a school that instilled cultural pride and empowered children to be embrace their Mexican and American culture.

These classes were taught by Mexican American women, such as Isabel Verner, who was the first to pilot the program in Ganado, Texas.37 The success of the LS400 schools in Texas served as a model for the nationally sponsored Head Start Program that emerged during the “War on Poverty” initiatives by President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration.

The East LA School Blowouts

In March of 1968 in East Los Angeles, California the country witnessed a series of walkouts across high schools like never before. According to La Raza Newspaper, “The first 15 days of March of the year 1968 will be known in the ‘new’ history of the Southwest as the days of the BLOWOUT. Chicano Students define Blowout as ‘high school students walking out for a better education.’”38 An estimated 15,000 students walked out of classes from seven high schools, what became known as the East LA blowouts. The students gathered the results from surveys they created and compiled a list of 26 student demands that addressed a range of issues with academics, administration, facilities, and student rights. In their demands, students called for culturally relevant and responsive education, critiqued the lack of college preparatory courses, and the punitive school culture. The list of demands was presented to the LA Board of Education on March 28, 1968 only to be denied in front of the more than 1,200 community members present.

Sidebar

To view the proposals presented by the Educational Issues Coordinating Committee (EICC) to the Los Angeles Board of Education on March 28, 1968 visit Latinopia.com (March 6, 2010).

The walkouts were made possible because the students had the support of their community. Salvador “Sal” Castro, a teacher at Lincoln High School, who extended his support to the students, recruited students to attend the Chicano Youth Leadership Conference,39 a space that was critical to nurturing political identities among Chicana/o youth of the time. Among those students was Moctesuma Esparza, a student of Mr. Castro at Lincoln High School. Moctesuma remembered those pivotal years for a PBS documentary titled, “Civic Leader Moctesuma Esparza: Educational Equity”

A group of young Chicano students, we were 10th graders, 11th graders, formed an organization called Young Citizens for Community Action. And we would get together on weekends and we would talk about what was wrong, what was wrong in our schools, what was wrong in our lives and our community? Why was it that our teachers were not encouraging us to go to college? We had plenty of shop classes at Lincoln but almost no honors classes. We were being trained to be laborers. The schools were like prisons. We couldn’t use the restrooms. We were punished. We were spanked for speaking Spanish. And all of the students were unhappy about that. We talked about what we could do to make a difference? ‘All right, we need to take a lesson from what's going on in the rest of the world.’ The plan was, we walk out.40

Young Citizens for Community Action initially formed in 1965, while Moctesuma was in high school, and eventually evolved into the United Mexican American Students (UMAS) and Brown Berets while he was a student at the University of California Los Angeles. Moctesuma recounts the role of university students in mentoring local high school students stating,

They wanted to be organized. They wanted to do something, and so what we did at that point as college students was provide them context and assist them. And they made all of their decisions. It was an extremely democratic movement. The high school students were very jealous of their own prerogatives and of their own independence. And what we did as college students was to provide a safety net for them once they did decide to walk out, to act as monitors and as security for the movement, and provide resources and the community support system to then begin to reach out to parents and to labor movements and to the clergy. So we went about it very methodically. It took us a couple of years.41

The students in East LA had support from their parents, political organizations, and former students. By offering the community independent forms of communication through newspapers such as La Raza, Inside Eastside, and The Chicano Student, activists in East LA were able to control the narrative and inform the community, galvanizing their support, which was crucial to their success.

The movement that was forming around the walkouts was actively repressed by school administrators and law enforcement agencies. High school seniors who were recipients of scholarships were threatened with having their scholarships taken away. Students and their supporters were brutalized by the Los Angeles Police Department and arrested. The LAPD issued an arrest to 13 Chicano men for “disturbing the peace” and conspiracy charges. Those arrested were better known to the community as the East LA 13, and among the youngest was Moctesuma who was only 19 years old at the time.42 Mr. Castro was also among the arrestees and consequently fired as a result. The decision to fire Mr. Castro was reversed after the community demanded he be reinstated and occupied the school board room until he was. The political repression of activists at this time was part of the systemic counter insurgency efforts of law enforcement, most notably, the FBI’s Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO) that targeted political organizations, surveilled their activities, infiltrated their efforts, and ultimately used that intelligence to incarcerate an entire generation of activists leaders.

The 60s was a crucial time for youth to develop their political identities and exercise their freedom of speech in efforts to change their schools and society. The walkouts, like other sit-ins and marches of the era, used non-violent resistance to protest systemic racism. Crucial to creating an alternative educational system as was proposed by the students in their demands and in the aftermath of the walkouts, was the need for greater control over the decision-making process in schools and the district. While the students did not achieve all of their demands, they were successful for bringing generations together and laying a foundation to their own political trajectory.

The Formation of Chicano Studies and Ethnic Studies

During the civil rights movement, there were many alternative models to mainstream education that emerged from historically minoritized communities, most prominently within the Black community, from the Citizenship Schools (1945-1965) that were a response to the racist literacy tests that disenfranchised Black voters to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s (SNCC) Freedom Schools that began in the summer of 1964 to encourage Black Mississippians to think independently and act creatively. Not to mention in 1969, the Black Panther Party (BPP) launched Liberation Schools that offered a political education to resist power structures.

Within traditional institutions of higher education, BIPOC as minority groups on college campuses all across the state supported each other and united in their demands for change. In the Bay Area, the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF), a coalition of multiracial and ethnic groups of students and organizations at San Francisco College and University of California, Berkeley, spearheaded a movement for ethic studies. TWLF specifically employed the term “third world” as a radical identity that positioned itself as anti-imperialist, anti-colonial, and anti-racist.43 From the beginning of its formation, ethnic studies recognized distinct histories in the U.S., and proposed an internationalist connection of solidarity to liberation struggles in the Global South, in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Pacific Islands. Led by the Black Student Union, the TWLF joined together to form two strikes that began in 1968 and presented a list of 15 demands, among the list was to create a School of Ethnic Studies. It was in these times that ethnic studies was defined as groups of the Third World, Chicano/Latino studies, African American studies, Asian American studies, and Native American studies. As noted by Ziza Delgado, ethnic studies emerged within a radical political framework that included elements of culturally relevant education, but were not limited to only the study of culture.44

Globally there were revolutionary struggles against colonialism, imperialism, racism, white supremacy, and capitalism. In the midst of these movements, there was the return of WWII Chicano veterans who gained access to higher education unlike ever before as a result of the GI Bill and the American GI Forum that ensured veteran rights were respected. These veteran students among others gave way for the formation and growth of activist student organizations such as United Mexican-American Students (UMAS). The population of students of color at the University of California, Santa Barbara was severely low, and there were only about 50 Chicano/Latino students. At UC Santa Barbara, students from UMAS joined in solidarity with the Black Student Union (BSU) and the mostly all-white Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) under what they called United Front to take over and occupy the University Center. They called for a free-student run university that incorporated instruction on revolutionary movements, global capitalism, and Marxism.

That same year at UC Santa Barbara, Chicana/os across the states came together under the newly formed Chicano Coordinating Council on Higher Education to create a blueprint for the formation of Chicano studies. The result was a 155-page manifesto titled, El Plan de Santa Barbara: A Chicano Plan for Higher Education (“El Plan”) that outlined the three-fold function of the university: teaching, research, and public service.45 The blueprint opened with a quote from Jose Vasconcelos, former Secretary of Public Education of Mexico, that captured the sentiment of the time. “At this moment we do not come to work for the university, but to demand that the university work for our people.” El Plan outlined the importance of the newly established student support program, Educational Opportunity Program (EOP) and the need for a unified national student-led organization, which became Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano Aztlan (MEChA). It called for the formation of research centers and the institutionalization of Chicano Studies departments.

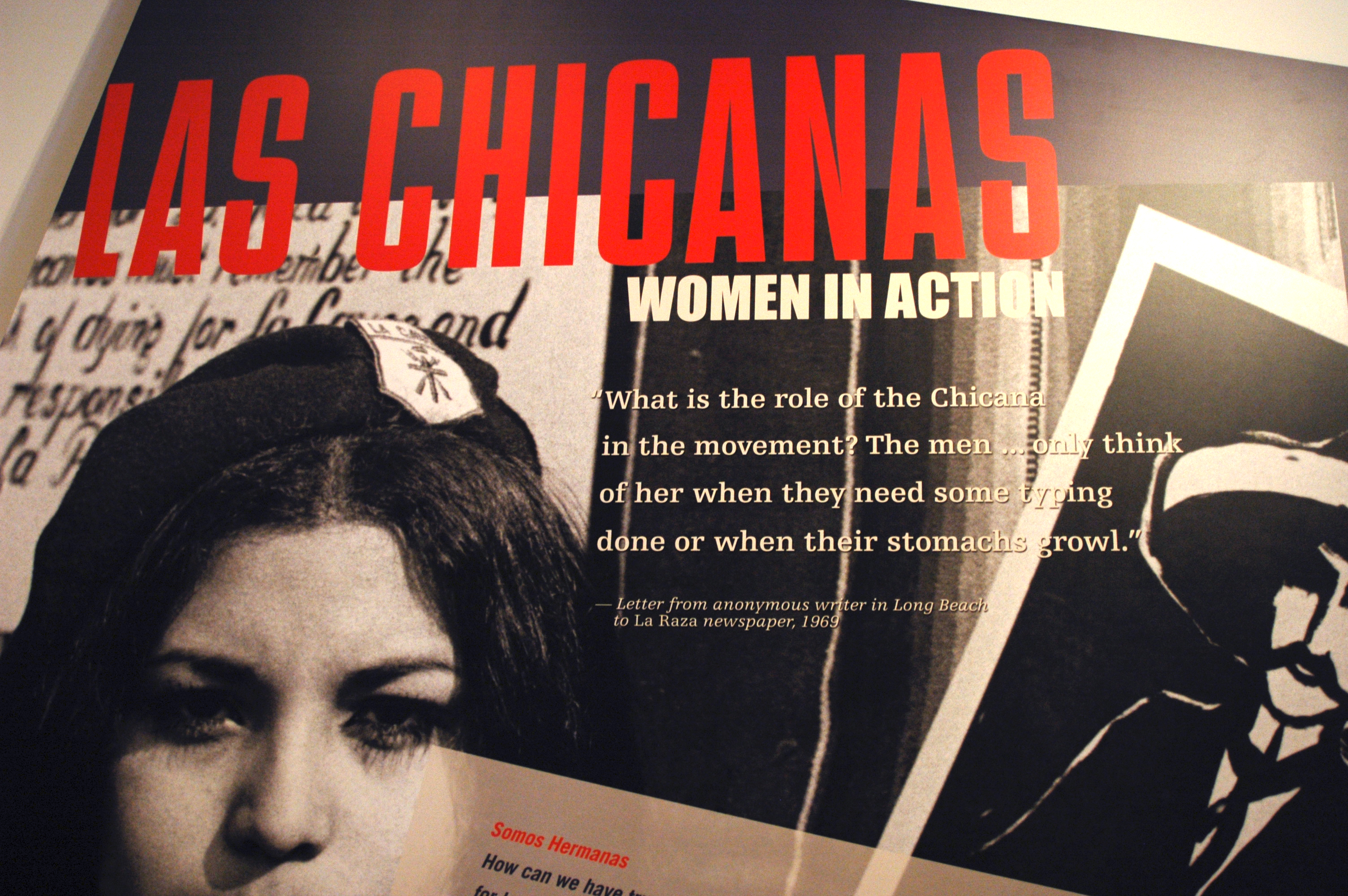

While El Plan and the Chicano movement in general were instrumental in paving new directions for the Chicano community, they were not absolved of critique. In “Sexism in Chicano Studies and the Chicano Community” Cynthia Orozco identifies the sexist ideologies that made gender a secondary issue to race and class.46 Orozco offered a sobering critique of Chicano studies as an academic discipline, citing the first edition of Rodulfo Acuña’s Occupied America (1972) and its failure to incorporate Chicana history, leadership, and contributions. Orozco even pointed out how “La Chicana” was a tokenized course, often the only course in that interrogated issues of gender, patriarchy, and what feminists of color at the time articulated as “triple oppression” and ultimately intersectionality. In Orozco’s view, El Plan was truly a “man-ifesto” that lacked a feminist vision. Instead, Orozco provides a Chicana feminist revision of El Plan renaming it to, “El Plan de Santa y Barbara” and that parts with the words of Señora Josefa Vasconcelos, “At this moment we do not come to work for Chicano studies and the community, but to demand that Chicano studies and the community work for our liberation too.”47 The feminist critiques of El Plan, Chicano studies, the Chicano movement, and the community at large gave way to Chicana studies and Chicana-led organizations (Review Chapter 5: Feminisms and Chapter 7: Social Movement Activity for more on this topic). Similarly, critiques over the lack of an interrogation of sexuality gave way to Jotería studies (Review Chapter 6: Jotería Studies). Figure 8.3.1 is from a history and cultural museum in Los Angeles that featured an exhibit on Chicana women leaders and activists.

Figure 8.3.1: “Las Chicanas” by Neon Tommy, Flickr is licensed CC BY-SA 2.0.

By this point, there was not a formalized ethnic studies field, but that’s not to say that the scholarship that emerged from traditional academic fields such as sociology, anthropology, history, along with other disciplines did not contribute to the development of ethnic studies. We can take for example, Chicana/o historians such as Vicky Ruiz and George Sanchez or Chicana/o sociologists such as Mary Pardo and Alfredo Mirande who emerged from traditional disciplines, but are regarded as foundational to the field. Furthermore, the role of public intellectuals outside of the academy were instrumental in carving new trajectories and uplifting political movements, such as anarchist journalist Ricardo Flores Magon and civil rights activist Adela Sloss Vento. From the beginning, ethnic studies redefined traditional notions of scholarship, intellectualism, and what we consider to be texts. The work of these scholars built a foundation for future generations of BIPOC scholars to build upon.

Unlike all other academic disciplines, Chicano studies, like ethnic studies, is more than just an academic discipline. Ethnic studies is a political project born out of struggle and critique of the institution it emerges within and education in general. It was not meant to conform to the status quo of these institutions, rather to serve as a powerhouse of change. From the beginning, ethnic studies was a community-driven project. And unlike other academic disciplines that make claims of objectivity and to present in unbiased or impartial ways, ethnic studies stands firmly against oppression of any form. Paulo Freire in The Politics of Education (1985) wrote about the impossibility of neutrality in the face of oppression stating, “Washing one’s hands of the conflict between the powerful and the powerless means to side with the powerful, not to be neutral.”48 Ethnic studies does not only study oppression, it directly engages with struggles for liberation that go beyond education.

The Backlash and Disinvestment in Public Education

As urban schools and cities experienced the changes of deindustrialization and disinvestment, the racialization of the welfare state through popular cultural deprivation theories continued to gain traction. Ronald Reagan’s deployment of the racialized and gendered trope of the so-called “welfare queen” throughout his 1976 presidential campaign trail demonstrated the growing binary of white “taxpayer” versus Black “tax-recipient.” Martha Escobar argues that the perceived threat of Black mothers as “breeders” of deviancy, criminality, and poverty is transposed onto Latina mothers, immigrant Latina mothers especially, who are viewed as unworthy and undeserving of social welfare services, including health and education.49 This growing fear over financing of Black and Latinx communities, along with the economic insecurities fueled the racialized tax revolts of the late 70s and 80s.

This white backlash enabled Caifornia laws such as Proposition 13 to pass, signaling a critical turning point for the finance of public education.50 Prior to 1978, public schools collected as much funding as was needed from local property taxes. This meant that neighborhoods with higher property taxes could collect more money for per pupil spending. Prop 13 set a 1% property tax limit across the state, where the assessed value could not grow more than 2% a year. The state, however, was either not financially able or willing to supply the needed local financing of schools that was not supplied through local property taxes. As a consequence, the most impacted were school budgets that cut nurses, counselors, librarians, vocational education, music and art programs, adult education, summer and after-school programming, and anything viewed as excess to the core academic curriculum such as elective courses.

Sidebar

In 1965, California had one of the highest rates of per-pupil spending in the U.S. Today, it is one of the lowest. This is the legacy of Prop 13. How much wealthier are white school districts in comparison to nonwhite ones? $23 billion.

The disinvestment in public education fueled by the racialized tax revolts of the late 70s and 80s made school districts heavily dependent on state budgets. These changes came at a time when civil rights victories fought to desegregate schools and students of color were redefining the role of education. In the 70s, desegregation efforts were often circumvented, like the case in Houston, Texas, when a school district claimed their district integrated Mexican “white” students with Black students, maintaining white schools intact.51 In other cases, white families fled to surrounding suburbs with LAUSD experiencing a drop of 20,000 white students after busing programs were introduced.52 This was part of the larger pattern of white flight in cities such as Los Angeles as suburbanization gave white families an opportunity to sell their home, maintain their wealth, and escape into the suburbs.

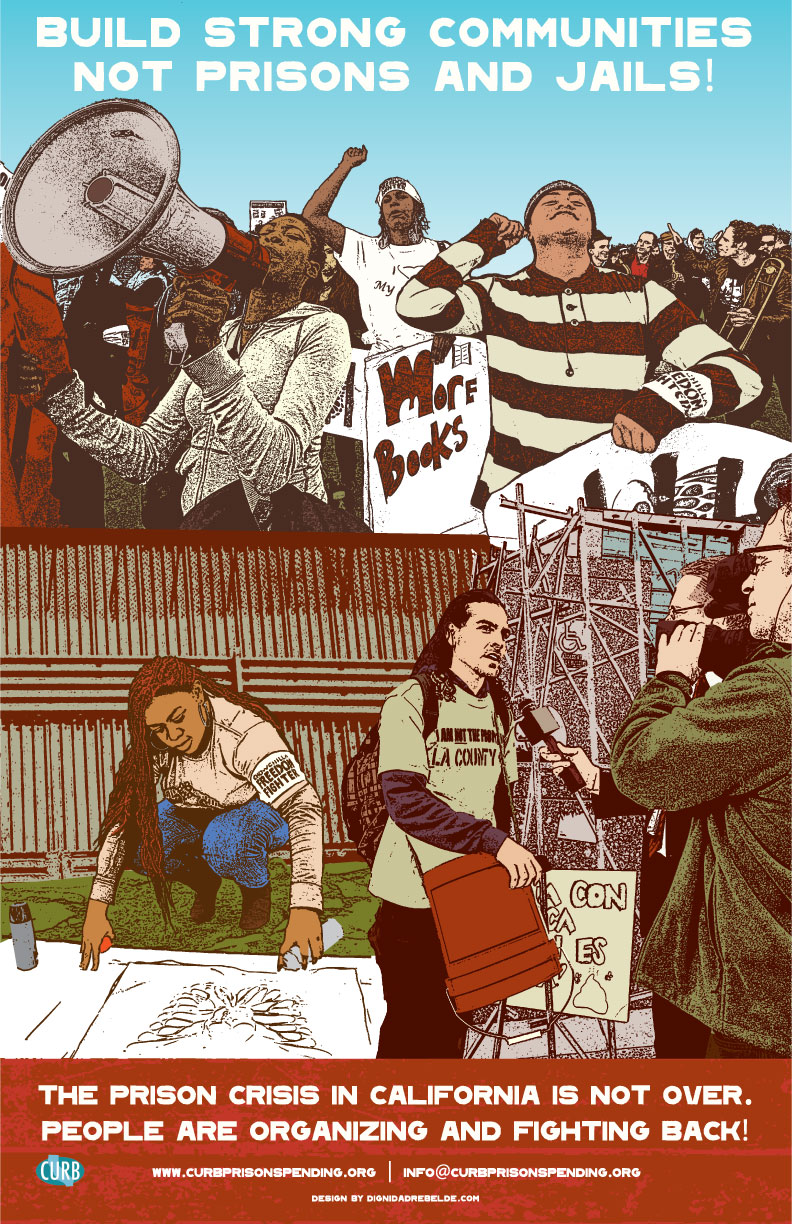

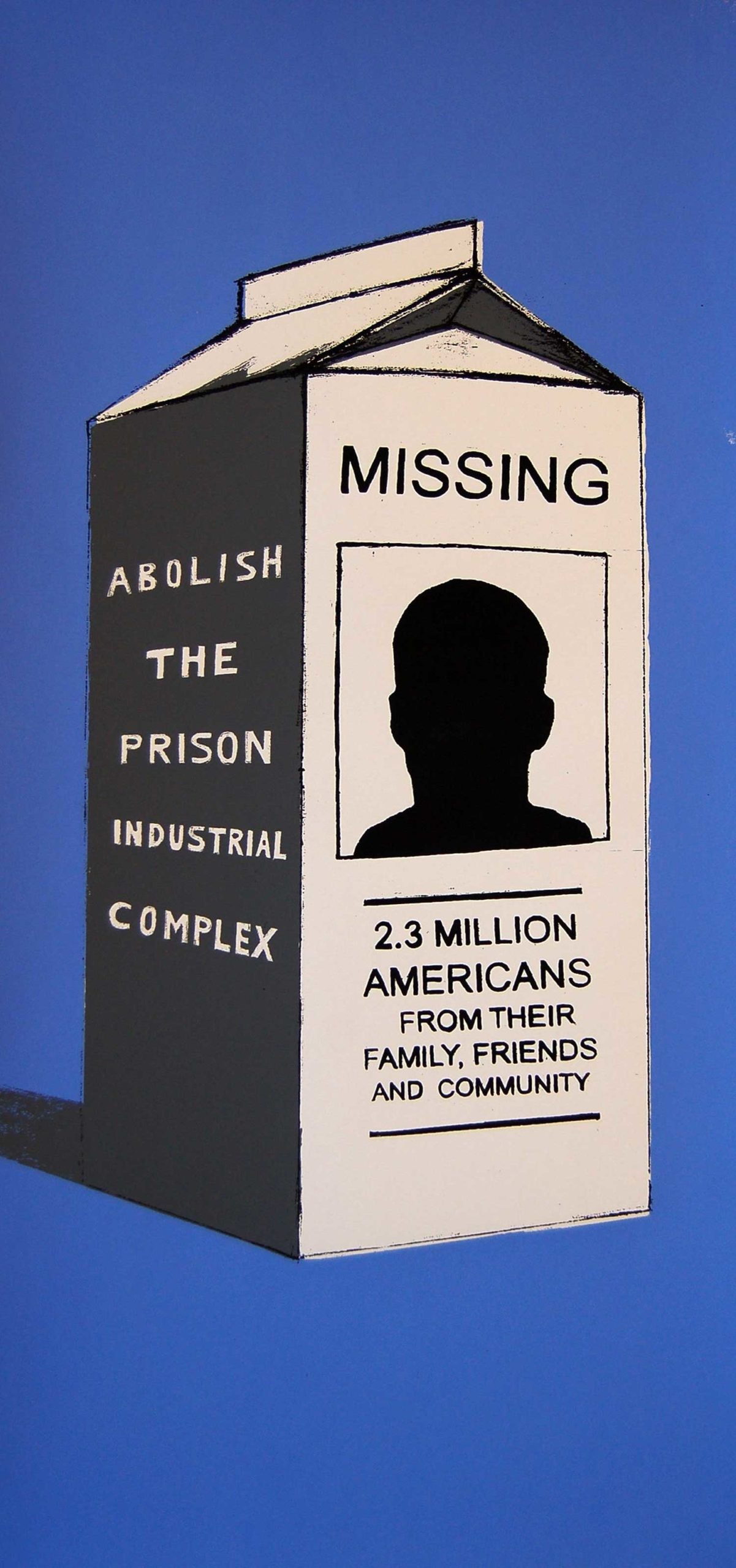

This issues have spurred activist responses. Figure 8.3.2 demonstrates critiques of criminalization and incarceration as responses to social problems. The poster reads, “Building strong communities not prisons and jails! The prison crisis in California is not over. People are organizing and fighting back!” Californians United for a Responsible Budget (CURB) is a broad-based coalition of over 70 organizations seeking to CURB prison spending by reducing the number of people in prison and the number of prisons in California. Similarly, Figure 8.3.3 is a 2008 poster that reads, “Abolish the prison industrial complex. Missing: 2.3 million Americans from their family, friends, and community.”

Figure 8.3.3: “Missing: 2.3 Million Americans” by Nicolas Lampert, Justseeds is licensed CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Footnotes

36 In Texas, Mexican families preferred sending their children to church schools or private schools known as colegios. El Colegio Altamirano was taught in Spanish so that Mexican children would preserve their culture.

37 For further reading on the LS400, review Erasmo Vázquez Ríos, “The Little School of the 400: A Mexican-American Fight for Equal Access and its Impact on State Policy,” (Master’s Thesis, University of Nebraska, 2013).

38 La Raza Newspaper, Vol. 1, No. 2. (March 31, 1968). La Raza Publication Records, 1001. Chicano Studies Research Center, University of California, Los Angeles.

39 This camp was intended to tackle the most pressing issues affecting Mexican American youth, such as gangs, access to college, and school dropout rates.

40 “Civic Leader Moctesuma Esparza: Educational Equity,” Youth Stand Up, PBS Learning Media, Accessed September 9, 2022.

41 Democracy Now! “Walkout: The True Story of the Historic 1968 Chicano Student Walkout in East L.A.” March 29, 2006.

42 The arrestees were Sal Castro, Moctesuma Esparza, La Raza newspaper editors Eliezer Risco, 31, and Joe Razo, 29, Brown Beret “ministers” Carlos Montes, David Sanchez, Ralph Ramirez, and Fred Lopez (ages 18 to 20), Carlos Muñoz Jr., 20, Gilberto Olmeda, 23, Richard Vigil, 27, Henry Gomez, 20 and Juan Sanchez, 41.

43 Jason Michael Ferreira, “All Power to the People: A Comparative History of Third World Radicalism in San Francisco, 1968-1974,” Ph.D. Dissertation (University of California Berkeley, 2003)

44 Ziza Joy Delgado, “The Longue Durée of Ethnic Studies: Race, Education and the Struggle for Self-Determination,” Ph.D. Dissertation (University of California, Berkeley, 2016).

45 As remembered by Fernando Negochea for the article by Armando Carmona, “El Plan de Santa Barbara: Beyond Studying Politics, a Legacy of Activism” UC Santa Barbara Alumni, Coastlines, Spring 2019. Accessed October 25, 2022.

46 Cynthia Orozco, “Sexism in Chicano Studies and the Chicano Community” (1984) NAACCS Annual Conference Proceedings. 5.

47 Orozco, “Sexism in Chicano Studies”, pg. 15

48 Paulo Freire. The Politics of Education: Culture, Power, and Liberation (Westport, Connecticut: Bergin & Garvey Publishers, 1985) pp. 122

49 Martha Escobar, Captivity Beyond Prisons: Criminalization Experiences of Latina (Im)migrants. (Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 2016)

50 Daniel Martinez HoSang, Racial Propositions: Ballot Initiatives and the Making of Postwar California, (Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2010)

51 Guadalupe San Miguel Jr., Brown, Not White: School Integration and The Chicano Movement (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2005)

52 “The Busing Controversy in Los Angeles as of 1980” CBS News. October 22, 1980.