7.2: Chicanx and Latinx Civil Rights Activism

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 138271

- Mario Alberto Viveros Espinoza-Kulick

- ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Roots of Contemporary Chicanx and Latinx Advocacy

Chicanx and Latinx communities have played an important role in the development of civil rights frameworks and policies in the United States. While these contributions are often overlooked, Chicanx and Latinx advocates have helped to establish principles of non-discrimination, mount legal struggles against racist policies, and mobilize multiracial coalitions for social and economic justice. This work has been carried out by generations of activists and made a lasting impact on U.S. and transnational legal structures.

For example in 1903, Mexican and Japanese farmworkers formed the Japanese-Mexican Labor Association (JMLA) and won a strike against the agricultural industry in Oxnard, California. The farm owners typically used workers’ ethnic or cultural backgrounds to encourage mistrust and competition, leading to lower wages and poor working conditions. The JMLA created a sense of unity and pride among Mexican workers in solidarity with Japanese communities. After tireless activism, including the death of one protestor, this group won better pay and ended the subcontracting system that was exploiting workers. After winning these victories, organizers of the JMLA attempted to join the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and continue as a labor union, but they were blocked by the AFL organizers, who said that members of Asian origin would not be allowed in the group. The JMLA organizers refused to accept this discriminatory policy and went on to continue their work and local organizing.

Juan Crow Racism

🧿 Content Warning: Physical Violence. Please note that this section includes discussion of physical violence.

Throughout the early 20th Century, The United States was in an era of Jim Crow and Juan Crow Laws, which legally enforced racist segregation policies that separated facilities and services for white people and excluded communities of color. Official segregation policies were matched by virulent racism and violence. The simultaneous dehumanization of both Black and Latinx communities can be seen in public signs that read, “No Dogs, No Negroes, No Mexicans,” as shown in Figure 7.2.1. One brutal instance of coordinated white supremacist terrorism occurred in Los Angeles in 1943, in what historians call the Zoot Suit Riots. During World War II, the deployment of massive numbers of working-age men into war created vacancies in the domestic labor force. This contributed to a range of social changes, including the entry of people of color and white women into industries recently dominated by white men. The deficit of labor in the agricultural industry also led the federal government to sponsor the Bracero program in 1942, allowing Mexican citizens to work in the U.S. temporarily. The growing Mexican and Mexican-American community in places like Los Angeles caused anxiety for elites in power interested in maintaining the status quo racial hierarchy. Media accounts used exaggerated and misleading language to spread fear and produce stereotypes of Black and Latino men as violent criminals. Latinas and Black women were also targeted for policing, although the stereotypes constructed threat primarily through hypersexualization.

Historical Spotlight: Analyzing the Zoot Suit Riots

The Zoot Suit Riots were an example of communities coming together to defend themselves and fight back against racism and violence affecting Latinx communities. This event responded to the pervasive violence that characterized the Jim Crow era, and it is an important backdrop for understanding the development of civil rights and legal advocacy strategies among Chicanx and Latinx communities. While reform strategies gained a lot of attention in the 1940s and 1950s, this was not the only approach to advocacy.

Zoot suits are outfits characterized by oversized wool coats that were popular among Black, Latino, and Filipino communities and inspired by the styles worn in Harlem, New York. The use of extra wool fabric to create large, baggy outfits was a symbol of status and prosperity, especially given the strain on fabric supplies during the war. Pachucos were especially known for their zoot suits and jazz music. In Figure 7.2.2, the image shows a group of young Mexican American boys who were rounded up and detained simply because of their zoot suit style. In Figure 7.2.3, the image shows a positive depiction and celebration of the zoot suit style as part of a stage performance in Mexico in 2010.

In 1943 in Los Angeles, white American sailors claimed that they were taunted by Pachucos, and proceeded to take cabs across town to East Los Angeles, a predominantly Mexican-American area, and start attacking any Latino wearing a zoot suit on the street. When the police arrived, they arrested the victims of these crimes rather than the assailants. Media spread word about these racist attacks, often mirroring the same beliefs as the police officers and blaming the folx wearing zoot suits for being attacked. On June 3, 1943, 50 servicemembers from the U.S. Navy marched through the streets of Los Angeles with clubs, beating Latinos wearing zoot suits or similar clothing.

Thousands more white military service members, off-duty police officers, and civilians were emboldened to violence over the following days. They beat and publicly stripped men wearing zoot suits, attacked and cut the hair of those with non-white hairstyles, like a ducktail, and rampaged throughout the city, unleashing violence on communities of color. The spread of violence can be attributed to the widespread racist ideologies of the assailants as well as the cultural and institutional response. Media messages reinforced racialized narratives, while law enforcement openly sanctioned the attacks, and the city government failed to intervene effectively. Eventually, all service members were banned from Los Angeles and the military police were brought in to stop the violence.

Sidebar: White Supremacy Repeats Itself

Retaliation by white supremacist groups is a common theme in the United States, and we can see examples of this today. For instance, in recent years, we have seen a rise in violent, mass shootings that target communities of color. In 2015, a white supremacist assailant traveled to a Charleston Church and murdered nine people. His statements online prior to the shooting, confession to the police, and statements after being tried and prosecuted all indicated that he was motivated by a racist ideology and felt no remorse for his actions. Similar to the attacks on people wearing zoot suits, the killer traveled away from his residence to encroach on a community of color’s space with the explicit goal of inciting violence and harm.

In 2019, another violent assailant in El Paso, Texas attacked nearly 50 people, killing 23, and then publicly stated to the police that he was motivated by a desire to kill as many Mexicans as possible. In 2022, different white supremacists killed ten people in a mass shooting targeting Black people at a grocery store in a Black neighborhood in Buffalo, New York and 21 people, including 19 children, at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas. Unfortunately, these are just a few of many examples of racially motivated violence against communities of color in the United States. For a more holistic picture of the status of hate crimes and violent extremist groups in the United States, you can explore the Statista website linked here.

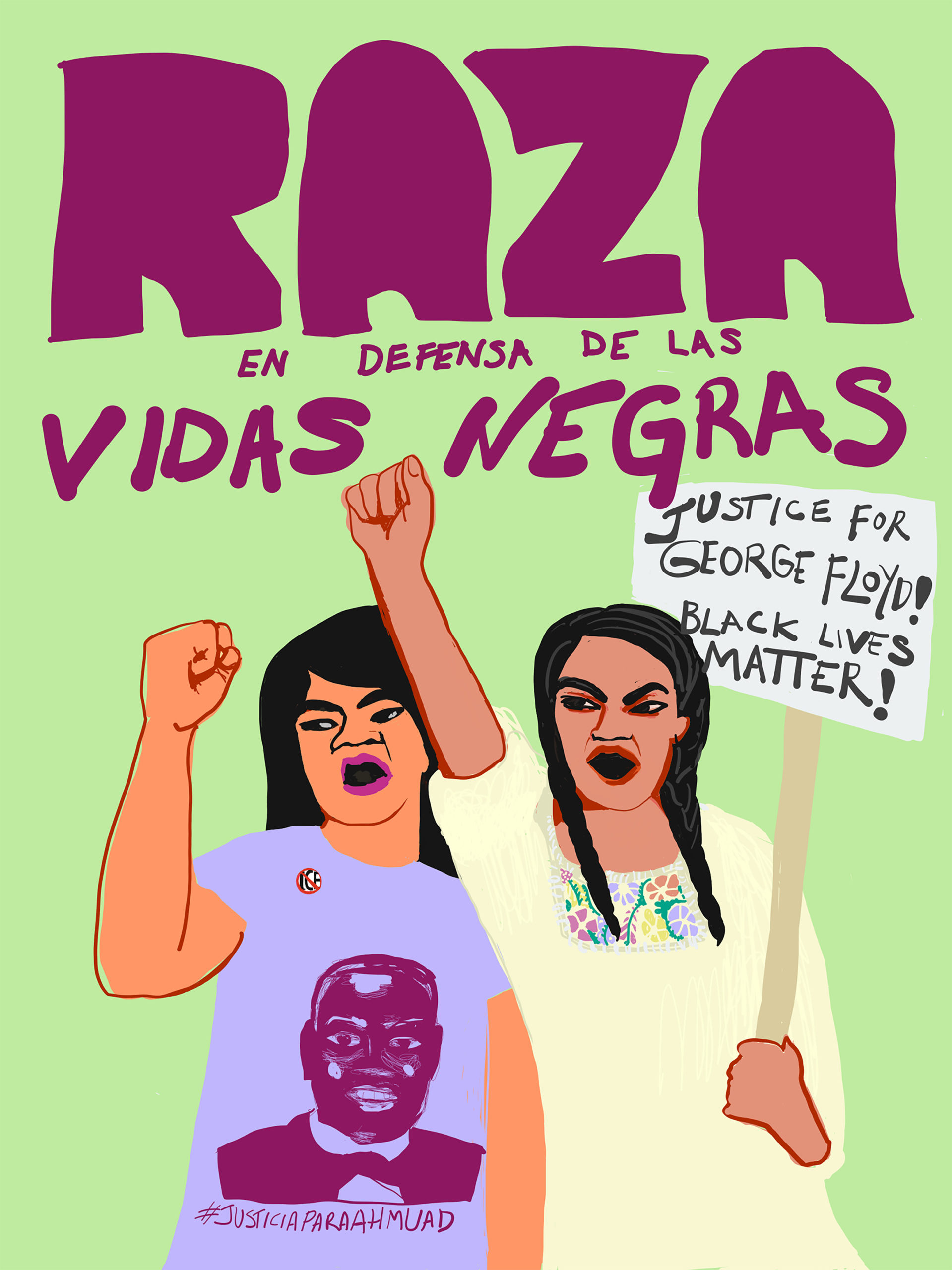

The experience of violence across different groups has also inspired solidarity among the people taking action to end racism and white supremacy. For example, in Figure 7.2.4, there is a poster that reads, “Raza en Defensa de Las Vidas Negras” (“La Raza in Defense of Black Lives”) with two Latinas protesting for Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, and Black Lives Matter.

Civil Rights and Legal Advocacy

🧿 Content Warning: Physical Violence. Please note that this section includes discussion of physical violence.

The League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) was a frontrunner in the struggle for civil rights, as it was formed in 1929. This group advocates for civil rights and has helped contribute to social, policy, and legal change. For example, members were involved in Hernandez v. Texas, which dealt with the exclusion of Mexican-American people from jury service. The Hernandez case began because an all-white jury convicted Pete Hernandez of the murder of Joe Espinoza. Hernandez’s attorney sought to invalidate this verdict on the basis of the jury, as Mexican Americans were formally excluded from jury service. A lower court denied Hernandez’s case and claimed that people of Mexican origin are not included in the “equal protection” clause of the 14th Amendment of the Constitution because the Census legally classifies Mexican Americans as white. In its unanimous decision, the Supreme Court affirmed in 1954 that equal protection does in fact apply to Mexican-origin people, as well as multiple racial groups who have experienced historical marginalization and systemic oppression. This is just one of the many struggles that took place to dismantle racist legal structures affecting Chicanxs, Latinxs, and other people of color in the United States. In Section 8.2: The Struggle for Equality, 1900-1954, you will learn more about the 1947 Mendez v. Westminster case which was a landmark decision for desegregation in public schools and paved the way for the Brown v. Board of Education decision at the federal level.

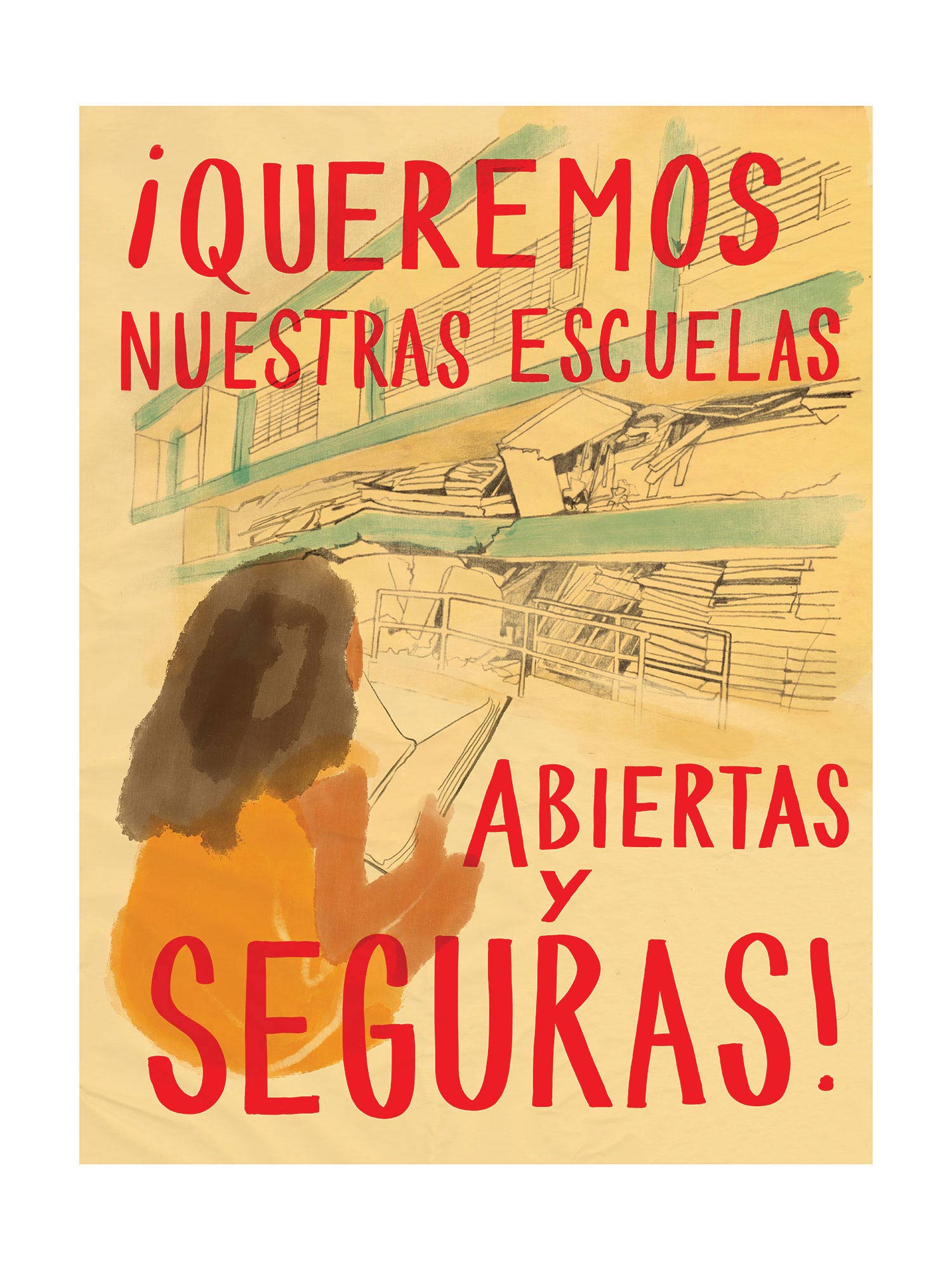

Even as the legal structures of racial segregation began to falter, Latinx communities still experienced exclusion and discrimination in all arenas of life. In Figure 7.2.5, there is a poster that reads, “Queremos Nuestras Escuelas Abiertas y Seguras” (We want our schools to be open, secure, and safe.”) Public schools were failing Chicanx and Latinx communities. Students were receiving sub-par educational preparation, resulting in the lowest reading rates and graduation rates of any racial or ethnic group. Teachers did not represent their community and the curriculum rarely incorporated any culturally or historically relevant content. Students were being pushed out of school and tracked into vocational career pathways, meaning that not many Chicanx and Latinx folx had the opportunity to attend college. This also contributed to Chicano and Latino men being drafted in disparate numbers for the Vietnam War. Local police were constantly surveilling and profiling Mexican-origin and Latinx communities. Negative stereotypes of Chicano and Latino males as gang members and drug dealers created stigma in their daily lives and have long-term negative implications. American labor markets restricted opportunities to well-paid jobs and representation in unions, forcing Chicanx and Latinx people into underpaid employment with poor working conditions. In the 1960s, the growing momentum of civil rights advocacy, along with opposition to the Vietnam War, the growing agricultural labor economy, and federal Native American relocation policies contributed to the collective feelings of unrest and resistance.

Identity Politics and Chicanismo

In Section 2.1: Defining Latinx Demographics, you learned about the various labels and identities associated with Chicanas, Chicanxs, Chicanos, and Latinas, Latinos, and Latinxs. In the context of social movements, Chicana/o/x identities began to emerge in the 1960s, led by Mexican-origin communities in response to the gains of Mexican American groups, as well as critiques of the integrationist and assimilationist perspectives in the reform-focused advocacy of the 1940s and 1950s. Access to mainstream institutions did not yield the gains promised by previous generations.5

The term Chicano emerged to cultivate a sense of cultural and ethnic pride and mobilize community members to commit to revolutionary change and re-organizing societal institutions around inclusion and justice. The Chicano movement originated as a set of diverse local and regional struggles for social justice, civil rights, and political representation throughout the U.S. Southwest and Midwest. Activists, men and women, young and old, demanded equal rights under the law, an overhaul of the educational system, access to decent housing, community-run healthcare, and an end to police brutality and the Vietnam War. There was no singular origin point of the movement, and scholars still debate the histories of how the Chicano identity formed and spread among multiple groups. However, most agree that the late 1960s and early 1970s, especially 1969-1973, were characterized by a surge of Chicano activism and high rates of mobilization throughout the U.S. While local groups often had specific, tangible goals that they were working to achieve, the shared mission uniting these efforts was “to construct a new political subject for the world stage—the Chicano—who sought to transform his subjugation as an ethnic Mexican living in the United States into a persona much more powerful and respected in daily life.”6

A simplistic definition of Chicano / Chicana / Chicanx is that these are simply a replacement for the term Mexican-American. For example, Oxford Learner’s Dictionary defines Chicano as “a person living in the US whose family came from Mexico.” From this point of view, Chicano can be derived from “Mexicano.” By removing the “Me” at the beginning, the word shortens to “Xicano.” In Spanish, the X is pronounced like “Ch” in English, so the term becomes “Chicano,” and Chicana and Chicanx then form the feminine and gender-neutral versions of the word. While the term is sometimes used this way, the simplistic definition hides the more complex history and political significance of the word as a collective identity-based in social movement advocacy, which you first learned about in Chapter 2: Identities.

First and foremost, the term Chicano was used first as a derogatory term against Mexican American communities, and activists reclaimed the term to give it a positive meaning associated with self-determination. Some groups retain the X at the beginning of the word: Xicano, Xicana, and Xicanx, in part to signal this association. By using the X, groups intentionally amplify the Spanish spelling of the word, affirming the cultural identities of bilingual communities as valid and valuable members of our cultures and societies on their own terms, rather than within the boundaries and expectations of the Anglo, English-speaking dominant group. This mirrors some of the policy demands of grassroots movement organizing, including protections against discrimination based on language use, and access to bilingual services and materials.

As Ana Castillo asserted in 1994, Xicana/o/x is “a political identity that emphasizes decolonization, rejection of cultural convention, and activism over origin or language.”7 In particular, by emphasizing “activism over origin or language” this recognizes that Xicanas, Xicanos, and Xicanxs may or may not speak Spanish, and may or may or may not have direct family lineage to Mexico or Latin America. In this sense, one is Xicana/o/x as a direct correlation to their ongoing contributions to activism for equity and justice for La Raza (all people of Latinx descent and their families).

The broad identity created by Chicano activists was able to bring together large groups to accomplish a shared goal. It also meant that the label can mean different things to different people, including contradictory perspectives on social movement tactics and strategies. For instance, some Chicanxs emphasized taking pride in their cultural roots and Indigenous heritage, while others sought to enact political revolution and create an autonomous nation-state. However, many Chicanos in the 1960s and 1970s were disconnected from Mexican lands, cultures, languages, and traditions by decades of immigration policy and because there were no educational opportunities in the school systems to learn about their own heritage. For more on the relationships between Latinxs and Indigeneity, you can review Chapter 4: Indigeneities.

Students Lead the Way: El Movimiento

A major influence on Chicanxs mobilizing in California took place on March 5, 1968, when 22,000 students walked out of their classes at Garfield, Roosevelt, Lincoln, Belmont, and Wilson High Schools in East Los Angeles. Also known as the East L.A. Blowouts, this demonstration brought attention to 26 demands, including changes in academics, administration, and facilities, as well as recognition of students’ rights and humanity. Students’ peaceful protests were met with police violence, and they were arrested and locked behind gates. The Board refused the students’ demands, and the police held a local teacher, Sal Castro, on charges of conspiring to disturb the peace for months. After round-the-clock protests at the School Board Office, Mr. Castro was released. However, the schools continued to resist structural changes, and activists became entrenched in a decades-long struggle to reform and transform L.A. schools. In Chapter 8: Education and Activism, you can go more in-depth into Chicanx and Latinx experiences in education and the formation of Chicanx and Latinx Studies fields.

Students and activists were also inspired by El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán during the 1969 Chicano Youth Conference hosted by Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzalez in Denver, Colorado. This document focused on translating the spirit of protest into organizational principles that can sustain action over time. The seven goals laid out in the plan pertain to unity, economy, education, institutions, self-defense, cultural values, and political liberation. The 1,500 young people at this conference shared these ideas with their communities and continued to mobilize toward specific action items and policy goals. The term Chicanismo was born at this event, and it emphasized the need to come together as Chicanos to make unified claims for racial liberation.

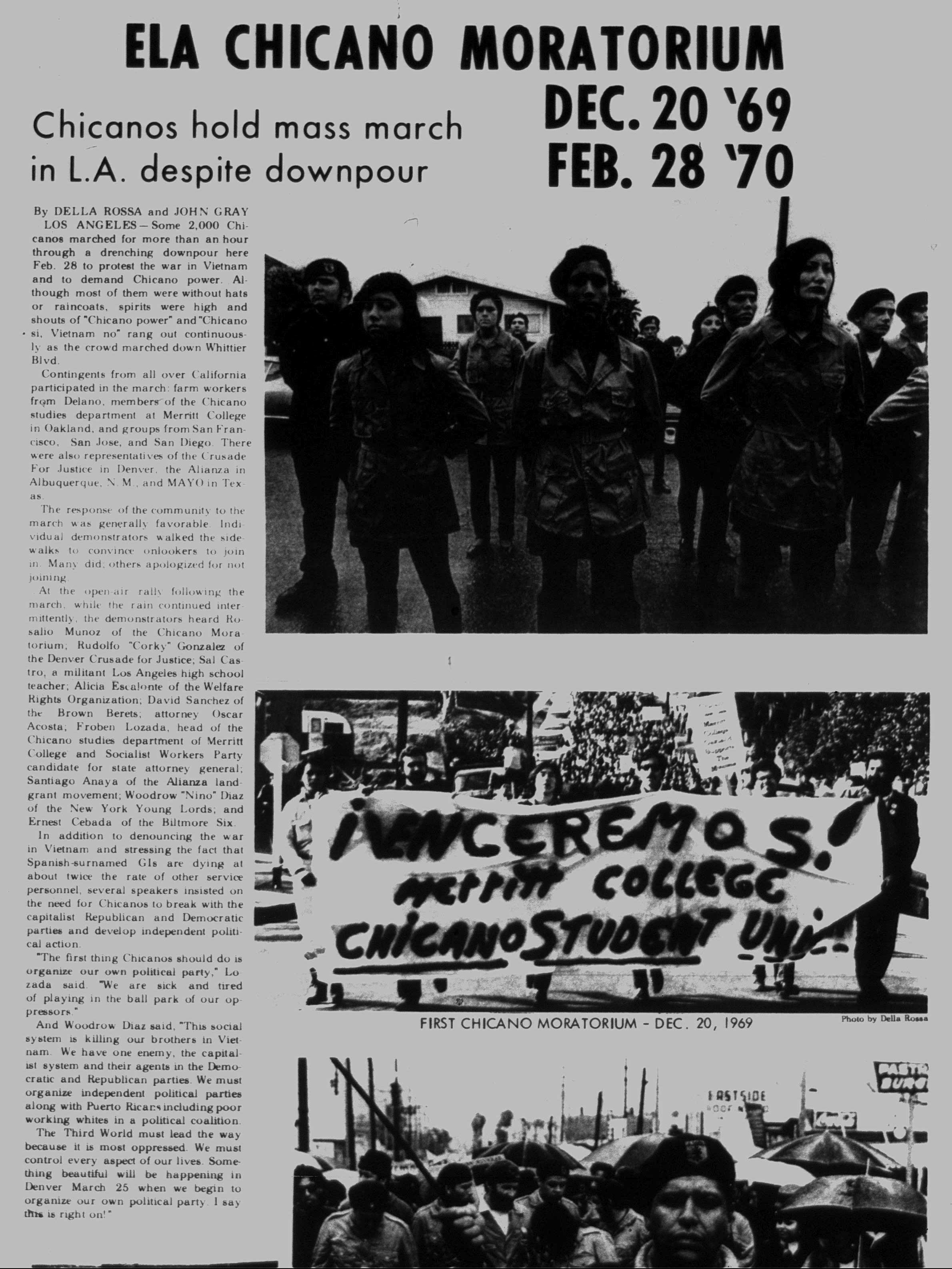

One major issue affecting the Chicanx community, especially Chicano men, was the disparate rate of being drafted into dangerous military service to wage war in Vietnam. The National Chicano Moratorium Committee Against the Vietnam War (or simply, The Chicano Moratorium) was a movement of anti-war activists. These efforts emphasized resistance to the war effort, both because the costly war was depleting resources needed to deal with social and economic issues facing communities living in the U.S. and because Mexican-Americans made up 20% of all casualties in the war, when they only accounted for 10% of the U.S. population at the time. In 1970, the group mobilized a demonstration of 30,000 people in East Los Angeles, which was the largest anti-war protest organized by any single ethnic group in the United States. News coverage of the Chicano Moratorium, including images of the protestors is shown in Figure 7.2.6.

Activist Spotlight: Corky Gonzalez

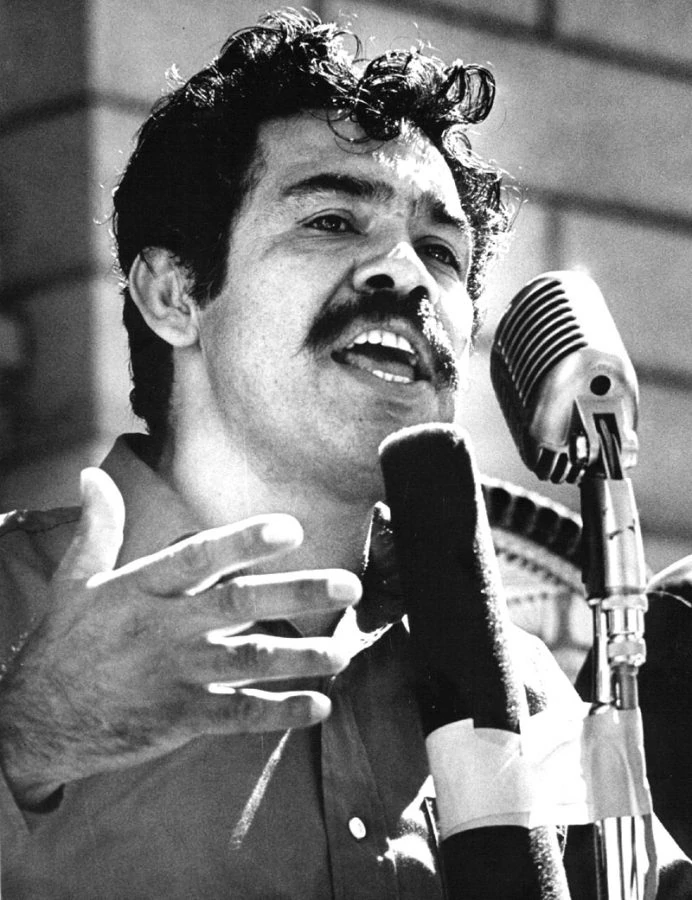

Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales was born on June 18, 1928. He was a boxer, writer, and Chicano activist. He worked on voter registration for John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign and successfully registered more Mexican Americans than at any other time in Colorado’s history. Gonzales founded Crusade for Justice in 1967, which was a militant organization of high school and college students who sought to increase educational opportunities and equity for Latinx students. He inspired the Chicano movement with his organizing and the poem, “I am Joaquín.” You can read the poem in English and Spanish on the Chicano History and Culture website linked here. A photo of Corky is shown in Figure 7.2.7.

Footnotes

5 Vilma Ortiz and Edward Telles, “Racial Identity and Racial Treatment of Mexican Americans,” Race and Social Problems: 4, no. 1 (April 2012): 41–56, http://dx.doi.org.proxygw.wrlc.org/10.1007/s12552-012-9064-8.

6 Francisco A. Lomelí, Denise A. Segura, and Elyette Benjamin-Labarthe, eds., Routledge Handbook of Chicana/o Studies, 1st edition (New York, NY: Routledge, 2018).

7 Ana Castillo, Massacre of the Dreamers: Essays on Xicanisma, First Printing edition (New York, NY: Plume, 1995).