8.2: The Struggle for Equality, 1900-1954

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 138277

- Lucha Arévalo

- ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Education for Social Control

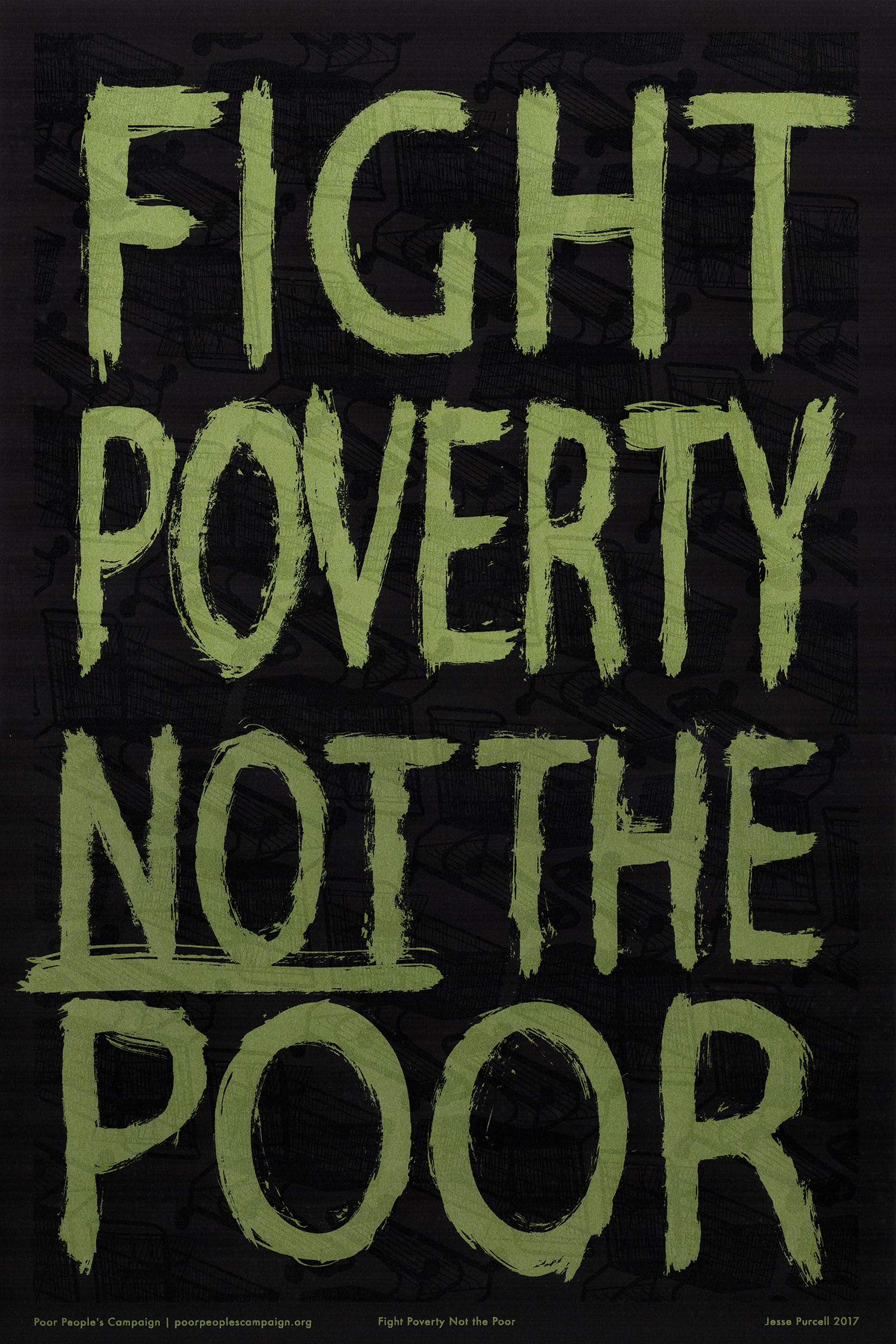

The educational system was historically created to sustain and perpetuate notions that equate whiteness and American as synonymous. For people of Mexican descent, the question of race has always been a complicated one. When the peace treaty that ended the U.S. invasion of Mexico was signed and the U.S. annexed ⅓ of Mexico, in exchange, Mexicans in the newly conquered territories were granted federal U.S. citizenship and racially categorized as white (Review Chapter 2: Identities). The racial re-designation of Mexicans under American colonization held no power in everyday life, especially in educational institutions as the practice of segregation of Mexican children is dated back to as early as the 1880s. Education is often perceived as a benevolent system and a gateway to social mobility, however, tracing it’s history allows us to see education as a site used to maintain racialized hierarchies and power. Figure 8.2.1 captures this sentiment today, reading, fight poverty not the poor. This is particularly significant for Latinx communities that continue to endure the historical legacy of colonization, white supremacy, racism, assimilation, xenophobia, and discrimination in schools.

At the turn of the 20th century, the 1896 Supreme Court decision in Plessy vs. Ferguson ruled that racial segregation was constitutional so long as it was equal. This historic ruling justified an era of segregation at a time when the U.S. also experienced the first major immigration wave of Latinxs, that is, 1.5 million Mexicans entered from 1900-1930 due to the Mexican Revolution.13 The ruling also came at a time when a Chinese family successfully won against the San Francisco Board of Education when their child was denied entry in school. The California Supreme Court decision in Tape v. Hurley (1885) effectively ruled that all minority children, including immigrants, were entitled to attend public schools in California. While anti-Asian hatred found new ways of creating “separate but equal” schools for Asian children,14 the question of whether children of Mexican descent could legally be separated would become central in this time period.

Mexican and Mexican American families lived in segregated colonias and barrios that often lacked basic necessities such as plumbing and electricity.15 Overt racism through signage read, for example, “We serve Whites only. No Spanish or Mexicans” was common in restaurants, theaters, bowling alleys, parks, and swimming pools (Review Section 7.2: Chicanx and Latinx Civil Rights Activism). When not visible, such as in schools, the practices of exclusion and discrimination were present. Unlike Native American and Asian American students that endured education codes that granted schools the right to legally segregate them, the practice of segregating Mexican American students prevailed despite their white racial categorization.

Figure 8.2.1: “Fight Poverty Not The Poor” by Jesse Purcell, Justseeds is licensed CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

Americanization and Eugenics

For children of Mexican descent, the denial of access to equal quality educational opportunities given to Anglo students was justified through Americanization efforts.16 The Americanization movement of the early 20th century was intended to help new immigrants assimilate into America’s civic culture and skilled workforce. Americanization aimed to change Mexican students who were characterized as dirty, un-Christian, and lacking social morals and etiquette. Central to this was assimilation, the process whereby a historically marginalized person or group voluntarily or involuntarily adopt the social, psychological, cultural, and political characteristics of a dominant group. As Chicano historian Gilbert Gonzalez noted, the first segregated school for Mexican children was established in Orange County, California in 1919 and by 1930, there were 15 Mexican schools throughout the county.17 Yet, not all children of Mexican descent were equally discriminated against. A study of Oxnard’s segregated school system in the early 1900s exposed how school officials used race, class, hygiene, and skin tone to identify “a few of the brightest, cleanest Mexican children.”18

Schools became one of the main functions of the Americanization movement, and for children of Mexican heritage, efforts instilled that their Mexican culture impeded their academic success. Language was often the target of these efforts and special classes were designed so as not to impede the education of their Anglo peers. Mexican children were often placed into lower-level courses or placed into segregated “Mexican schools” altogether.

In addition to Americanization, eugenics was a popular ideology that informed ideas of race and intelligence. Eugenics ideology is rooted in the belief that the white Anglo race is genetically superior and to maintain this group’s racial purity, it informed social policies, programs, and practices set out to control “undesirable” populations. For a review on this topic, you can also review Chapter 2. As noted by Valencia, Menchaca, and Donato (2002), “Historically, the rationale used to socially segregate Mexicans was based on the racial perspective that Mexicans were ‘Indian,’ or at best ‘half-breed savages’ who were not suited to interact with Whites.”19

Mexican American students were regarded as intellectually inferior, culturally backward, and linguistically deprived. One of the key instruments to determine a person’s intelligence prominently used in schools was the Intelligence Quotient (IQ) test, a standardized test that supported the racialized view that students of color were intellectually inferior to whites because they scored a lower IQ score. This institutionalization of racism systematically tracked students in lower-level courses, and vocational trade training, and deprived them of opportunities to succeed.20 Although Mexican children were classified as white, they “were by far the most segregated group in California public education by the end of the 1920s.”21

The Lemon Grove Case

School segregation was met with resistance from families throughout the Southwest. On July 23, 1930, the all-white school board members of the Lemon Grove School District decided to place all students of Mexican descent attending the elementary school in an inferior quality, two-room building near the Mexican colonia of Lemon Grove, California. The school board members cited concerns with overcrowding, sanitation, social morals, and language as justification for the separation. Essentially, the school board argued that white students were held back when teachers needed to cater to the needs of Mexican students. The concerns of the school board, along with the all-white Parent Teacher Associated that began the effort and the Chamber of Commerce who supported the move, relied on coded language. Coded language is a practice long used in policy in which race-neutral terms are used to disguise the racist motives that maintain power structures meant to sustain white supremacy. Citing clogged toilets and student overpopulation are euphemisms for race without stating race explicitly. Video 8.2.1 is of Luis Alvarez, grandchild of the plaintiffs in the Lemon Grove case, recounting how his familial history inspired him to become a historian.

Video: The Lemon Grove Incident and the Making of a History Professor with Luis Alvarez

Video 8.2.1: “The Lemon Grove Incident and the Making of a History Professor with Luis Alvarez” YouTube, uploaded by University of California Television (UCTV), November 30, 2021, https://youtu.be/1vsM9Ep06EM. Permissions: YouTube Terms of Service.

In this 10 minute video, Luis Alvarez shares how the story of his grandparents when they were students at the segregated school in Lemon Grove inspired him to become a historian.

Chicano historian Luis Alvarez, whose grandparents, Roberto and Mary Alvarez, were students in Lemon Grove during that time, recounts the political context of that era in the following way.

This is an important chapter in the history of Chicanx and Latinx San Diego and not just because they won, the Mexican community in Lemon Grove took a stand against fierce odds. They challenged the white power brokers in their community that ran the school board. They risked losing their jobs amid the Great Depression. They faced the prospect of deportation during what was a nationwide repatriation campaign that saw more than 600,000 Mexicans returned to Mexico, including countless numbers of Mexican American-born children. And yet they came together, in the tradition of immigrant mutualistas to form the Lemon Grove Neighborhood Association and fight.22

Responding to oppressive conditions with the aid of mutualistas was essential. Mutualistas are community-based mutual aid societies created by Mexican immigrants to connect them with a network that links their homeland and new home with resources, support, and a community. The Mexican parents drew upon their social networks and organized to boycott what they referred to as a caballeriza (horse stable or animal farm). With assistance from the Mexican embassy and newly formed organizations such as LULAC,23 they won what became the first successful school desegregation case in Alvarez vs. The Board of Trustees of the Lemon Grove School District (1931). To learn more about the founding of LULAC, review Section 7.2: Chicanx and Latinx Civil Rights Activism). The court ruled that children of Mexican heritage were unlawfully segregated because Mexicans are racially considered Caucasian, therefore, schools cannot segregate Caucasian students from other Caucasian students.24

Film Spotlight

The Lemon Grove Incident (1986) The 1986 documentary film, The Lemon Grove Incident, provides a glimpse into historical footage of the time, oral histories, and re-enacted scenes to take viewers back to life in Lemon Grove, CA during the first successful school desegregation case in the state. Explore San Diego. The Lemon Grove Incident (1986). PBS.

Pause and Reflect

Mutualista (mutual-aid) societies are used by many communities of color to survive economic hardship and provide a support network for newly arrived (im)migrants. Have you witnessed any mutualista practices in your school, community, and/or family?

In California, the case against the Lemon Grove School District helped to defeat growing political attempts such as the 1931 Bliss Bill that was introduced by Assemblyman George R. Bliss of Carpinteria to re-categorize Mexicans as “Indian” rather than “white.” A legal redefinition of Mexican children as “Indian children whether born in the United States or not” would have justified segregation as was done with Black, Asian, and Native American students.25 The Lemon Grove case is noted as the first successful legal challenge to school segregation in the U.S.26 While victorious for the local Mexican families of Lemon Grove, resistance to segregated schools continued across California and the Southwest.

The Mendez et. al. Case

In California, de jure, the legal practice of segregation ended as a result of the class-action lawsuit, Mendez, et. al v. Westminster School District (1947).27 (For further reading on the Mendez case, review Section 7.2 Chicanx and Latinx Civil Rights Activism). At the height of WWII, when Japanese American families were forcibly evacuated and relocated to internment camps, among them was the Munemitsus family of Westminster. The Mendez family moved to Westminster from Santa Ana because an opportunity opened to lease and run a 40 acre asparagus farm that belonged to the Munemitsus family.28 The Mendez family managed this farm that was labored by Mexican Braceros. To learn more about the Bracero program, review Section 7.4: Labor, Farmworker, and Immigrant Movements, or Section 4.4: Gender, Sexuality, Migration, and Indigeneity.

Video: Mendez v. Westminster: For All the Children

Video 8.2.2: “Mendez v. Westminster: For All the Children” YouTube, uploaded by Sandra Robbie, July 9, 2020, https://youtu.be/F46Mlzt2tFc. Permissions: YouTube Terms of Service.

This 33 minute video details the historic case Mendez vs. Westminster and features Sylvia Mendez.

In 1944, Gonzalo and Felicita Mendez’s Mexican-Puerto Rican children were denied enrollment into their neighborhood school, the same school where their nieces attended. In an attempt to enroll their children, their aunt went to the school. The Mendez daughter, Sylvia, remembered that moment as an adult in Video 8.2.2, which is Sandra Robbie’s documentary, “Mendez v. Westminster: For All the Children.” A picture of Sylvia Mendez is shown in Figure 8.2.2.

So when we got to the school they told her, "Mrs. Vidarri, you can leave your kids here but your brother’s kids will have to go to the Mexican school. The Mexicans are segregated here in Westminster. They have to go to the Mexican school."29

Since her Mexican American aunt married a French man with the last name Vidaurri and their children were light-skinned, easily passing as white, they were allowed to enroll in the “white” neighborhood school. The colorism, that is, the prejudice or discrimination based on dark skin color, enacted by the school demonstrates the complexity and proximity of whiteness available to some in the Mexican community and not to others.

Figure 8.2.2: “Sylvia Mendez” by Duke University, Wikimedia Commons is in the Public Domain, CC0.

In this scenario, we learn that whiteness was not necessarily available to all Mexicans, including the Mendez family who despite their higher class standing from operating a farm and owning a cantina (bar) business in Santa Ana, they remained unsuccessful in accessing the “white” school because their skin was much darker than that of their relatives.30 What their class standing did give them, however, was the financial means to fight segregation legally in court. Ultimately, the Mendez case was successful it but did not go unchallenged in the Court of Appeals. The Mendez case received an outpour of support from organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), and American Jewish Congress (AJC) that all submitted briefs in support of their case. In their brief, AJC mentioned, “We believe, indeed, that the Jewish interests are inseparable from those of justice and that Jewish interests are threatened whenever persecution, discrimination, or humiliation is inflicted upon any human being because of his race, creed, color, language, or ancestry.”31

The solidarity of all the organizations and community leaders who were able to recognize that while they may be racialized differently, there are shared interests in challenging racism. They were able to prove that separate schools violated the equal protection clauses of the 14th Amendment of the Constitution, not on grounds of racial discrimination, but national origin because after all, no one contested whether the children were white, but rather, that discrimination was based on their Mexican and Latin national origin.32 As a result of growing state-wide political momentum in support of desegregation, state Governor Earl Warren signed legislation in the state to repeal state law segregating American Indians and Asian Americans, effectively outlawing state-sanctioned de jure segregation.33 Figure 8.2.3 showcases the first issue stamp released in 2007 celebrating 60 years after the Mendez vs. Westminster School District case.

Nationally, segregation was legal until it was challenged with the Supreme Court decision with Brown v. Board of Education Topeka (1954).34 Chicana sociologist and lawyer Marisela Martinez-Cola argues, the success of Brown was in part due to the over 100 legal challenges to segregation in state and federal courts, among them the victories led by Latinx families.35

Education has historically been an issue over civil rights denied, the right to a free public education. In this section we learned that Latinx families struggled for civil rights in education, paving the way for future movements in education. While segregated schools were now ruled unconstitutional, it is important to remember that white supremacist ideologies that inform a person’s racialized worldview and maintain divides do not change overnight. Latinx families continued to endure discrimination in housing, employment, and schools. The growth of urbanization and suburbanization across California would contribute to de facto segregation in housing and schools, introducing a new era of social change.

Footnotes

13 The Mexican Revolution represented the rise against the regime of Mexican President Porfirio Diaz, a regime that maintained a widening gap between the rich and poor. For more information of this time, review George J. Sánchez, Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, Culture and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993).

14 In response to the success of this state case, AB 268 was passed to establish separate schools for students of “Mongolian or Chinese” descent.

15 For further reading on what life was like, review “A Tale of Two Schools” Learning for Justice. August 7, 2017. To read about how segregated life allowed Mexican American families to preserve their heritage and cultivate community and traditions, review Jennifer R. Nájera, Borderlands of Race: Mexican Segregation in a South Texas Town (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2015). You can also engage with the interactive map on redlining in America, “Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America,” Digital Scholarship Lab and Julius Wilm, University of Richmond, Accessed July 20, 2022.

16 Eastern and Southern European immigrants were also included in Americanization efforts.

17 Sandra Robbie “Mendez v. Westminster: For All the Children” YouTube, 2003.

18 David G. Garcia, Tara J. Yosso, and Frank P. Barajas, “‘A Few of the Brightest, Cleanest Mexican Children’: School Segregation as a Form of Mundane Racism in Oxnard, California, 1900-1940,” Harvard Educational Review Vol. 82, No. 1 (2012): 1–25.

19 Richard R. Valencia, Martha Menchaca, Ruben Donato, “Segregation, Desegregation, and Interation of Chicano Students: An Overview of Schooling Conditions and Outcomes” in Chicano School Failure and Success: Past, Present and Future, 2nd Edition, Richard R. Valencia, editor (New York and London: Routledge, 2002); Martha Menchaca, “Chicano Indianism: A Historical Account of Racial Repression in the United States” American Ethnologist, Vol. 20, No. 3 (1993): 583–603.

20 The Whittier State School was a model for how to reform deficient and youth of color perceived as delinquent. For more on the history of race and science in California’s juvenile justice system, review Miroslava Chavez-Garcia, States of Delinquency: Race and Science in the Making of California’s Juvenile Justice System. (Oakland: University of California Press, 2012). Also, Martha Menchaca and Richard R. Valencia, “Anglo-Saxon Ideologies in the 1920s-1930s: Their Impact on the Segregation of Mexican Students in California” Anthropology and Education, Vol. 21, No. 3 (1990): 222–249.

21 As referenced in David G. Garcia, Tara J. Yosso, and Frank P. Barajas “A Few of the Brightest, Cleanest Mexican Children”: School Segregation as a Form of Mundane Racism in Oxnard, California, 1900-1940” Harvard Educational Review, Vol. 82, No. 1 (2012): 1–25.

22 “The Lemon Grove Incident and the Making of a History Professor with Luis Alvarez,” YouTube video, 10 minutes, University of California Television, November 30, 2021.

23 LULAC was first formed in Texas in 1927 for the purpose of ending discrimination. During this era, LULAC was instrumental in fighting school segregation cases. While many scholars have regarded LULAC as an assimilationist, anti-immigrant, anti-working class organization, Cynthia E. Orozco offers a re-reading of LULAC’s history in No Mexicans, Women, or Dogs Allowed: The Rise of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009).

24 The 1930 Census classified “Mexican American” as a race, receiving an outpour of backlash from the newly established organization, LULAC, to classify Mexicans as white. In 1940, there was a reclassification of Mexicans as white in U.S. Census as a protection mechanism in light of internment of Japanese Americans, which used Census data to locate Japanese-Americans. To learn more, read “On the Census, Who Checks ‘Hispanic,’ Who Checks ‘White,’ and Why,” Code Switch, NPR, June 16, 2014.

25 The Bliss bill called for an amendment to section 3.3 of the California school code which provided local school districts with “the power to establish separate schools for lndian children, and children of Chinese, Japanese, and Mongolian ancestry.” Assemblyman Bliss wanted the section dealing with Indian children modified to read “Indian children whether born in the United States or not” to give schools the authority to separate Mexican and Mexican American students from their Anglo counterparts on the grounds that “la raza children were Indians.” To read more about efforts to re-define Mexicans as “Indian” to justify legal segregation in schools, review Francisco E. Balderrama In Defense of La Raza: The Los Angeles Mexican Consulate and the Mexican Community,1929 to 1936 (Tucson, Arizona: The University of Arizona Press, 2018).

26 Roberto R. Alvarez Jr., “The Lemon Grove Incident” The Journal of San Diego History, Vol. 32, No. 2 (1986)

27 It is worth noting that while the Mendez family is often highlighted in this case, it was a class-action case that involved other families, including Thomas Estrada, William Guzman, Frank Palomino and Lorenzo Ramirez who joined as co-plaintiffs against school segregation in Santa Ana, Garden Grove, and Orange.

28 Janice Munemitsu, The Kindness of Color: The Story of Two Families and Mendez, et al v. Westminster, the 1947 Desegregation of California Public Schools (Janice Munemitsu, 2021); Luis Alvarez and Daniel Widener, ‘‘A History of Black and Brown: Chicana/o African-American Cultural and Political Relations,’’ Aztlan: A Journal of Chicano Studies, Vol. 33, No. 1 (Spring 2008), 147. This history is also captured in the children’s book by Duncan Tonatiuh, Separate is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez and Her Family's Fight for Desegregation (Harry N. Abrams, 2014).

29 Sandra Robbie, “Mendez v. Westminster: For All The Children” (2003) Youtube. 33 minutes.

30 For an in-depth discussion that complicates Mexicans proximity to whiteness and recognizes that they were part of the full racial spectrum, review Marisela Martinez-Cola, The Bricks Before Brown: The Chinese American, Native American, and Mexican Americans' Struggle for Educational Equality (Athens, Georgia: The University of Georgia Press, 2022).

31 Reproduced from Natalia Molina, ‘‘Brief for the American Jewish Congress as Amicus Curiae,’’ Westminster School District of Orange County, et al. vs. Gonzalo Mendez, (U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals 9th Cir. Oct. 28, 1946), p. 1.

32 The 1954 Hernandez v. Texas case validated that Mexicans, while racially white, were in fact treated as “a class apart” from whites.

33 The Governor signed the Anderson Bill which specifically repealed Section 8003 and 8004 of the California Education Code.

34 The leading attorney, Thurgood Marshall cited the Mendez ruling as a precedent during deliberations.