7.4: Labor, Farmworker, and Immigrant Movements

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 138270

- Mario Alberto Viveros Espinoza-Kulick

- ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

The United Farm Workers

Dolores Huerta co-founded the United Farm Workers (UFW) with Cesar Chavez in order to organize for labor rights and win recognition of poor working conditions and pay. The UFW was successful because it incorporated cultural strategies to mobilize immigrant and Indigenous communities. Huerta’s leadership was especially instrumental, although she was often overlooked when compared to Chavez. Despite this, her leadership was vital to the movement and mobilized 17 million people to boycott grapes in solidarity with farm workers. She is also credited with popularizing the phrase “¡Si se puede!” (Yes we can!), which was also a rallying cry during the Obama presidential campaign and continues to be used in social movement advocacy today. She continues to have an impact through the Dolores Huerta Foundation and was recognized by President Barack Obama with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2011 for her contributions to social and economic justice.

Working on behalf of communities that have been socially and economically exploited regularly brings Chicanx and Latinx movements into solidarity with other ethnic groups and immigrant communities.11 In California especially, struggles for worker justice have often been conducted in larger coalitions, including Asian Americans, Black communities, and Indigenous peoples. Immigrants have been a consistent part of the agricultural labor force, with employers exploiting the communities’ precarious legal and economic status by providing poor working conditions and low wages. While employers benefit from encouraging racial animosity between groups, social movements have used cross-ethnic solidarity to inspire successful collective mobilization. For instance, the UFW built from the successful mobilization in Filipinx communities, with leaders like Larry Itliong coming together with Latinx communities and migrants.

Labor and Farmworker Movements Today

While the UFW continues to operate today, it has become a centerpiece within a much broader movement for farmworkers and labor rights in agricultural industries. For example, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers sponsors campaigns for fair food industries, as well as against slavery within the agriculture industry, especially in the southeastern United States. In California, Santa Maria farmworkers organized a month-long campaign in 2021 to have local berry farms raise the wage for farmworkers who harvest strawberries. After collecting over 60,000 signatures nationwide, the growers agreed to a new rate of $2.10 compensation per box of strawberries. Organizers risked their jobs and their safety to protest the low wages, but they ultimately won in court and received a settlement from their employers and a commitment to have the management trained in workers’ rights.12

Farmworkers have been a frontrunner in the labor rights movement, inspiring changes that are later taken up by unions and through employee advocacy. However, workers in this industry also face disparate barriers to union representation and labor rights legislation. California Assembly Bill 2183, the California Agricultural Labor Relations Voting Choice Act, was proposed in 2022 to make it easier for farm workers to join or form a union by providing more options and protections when voting in a union election. Multiple unions have come together to support this because it would establish and affirm a strong standard for individuals’ right to collective representation in employment matters.

Beyond direct advocacy, farmworker movements also work to fill in the gaps left by current structures of exclusion. For example, in addition to the Dolores Huerta Foundation, the UFW Foundation, and other major organizations sponsor programs to provide farmworkers with food assistance, legal aid, housing support, educational opportunities, and other social services that are often restricted to citizens, or underutilized by migrant communities. During the COVID-19 pandemic, immigrants were excluded from federal stimulus programs, which prompted some community groups to fundraise and provide direct aid to undocumented peoples.

While labor rights issues and immigration issues are often handled by different policies, the movements that advocate around these topics share resources, cultural narratives, cross-ethnic solidarities, and leaders, including within Chicanx and Latinx communities. In Figure 7.4.1, the image shows a march sponsored by the UFW for immigration reform in northern California. The larger patterns in immigration policies contribute to many of the underlying factors of inequity in labor rights. Activists recognize this and work to support the mutually reinforcing goals of immigrant rights and labor rights to ensure fair treatment of all communities.

Immigrant Rights Movements

When examining migration from Latin America, it is important to recognize that the term “immigrants” often also refers to Latin American Indigenous peoples. For example, immigrants from Oaxaca, Mexico may also identify as Indígena (Indigenous) and speak a native language, such as Mixteco, Zapotec, Mazatec, Chinatec, or Mixé. Although immigrant and immigration policy sound alike, they each play different roles in shaping the ways immigrants experience life in the United States. Immigration policy is about the laws and policies that determine the process and number of people who can immigrate in various ways, whereas immigrant policy refers to the laws and regulations that impact immigrants currently residing in the country. For example, immigration policy reflects systems such as visa lotteries and temporary worker programs, whereas immigrant policy is enforced by federal institutions such as Immigration Customs and Enforcement (ICE). While some policies attempt to curtail migration by restricting access, the economic and military policies of the United States continue to encourage migration, including through dangerous and unauthorized migration.

In the United States, early immigration acts (e.g., the Immigration Act of 1875, the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, and the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act) enforced racial and ethnic (national) quotas on immigrants coming to the United States and, ironically, called for the removal of Native Americans. The use of quotas creates a baseline expectation that migration to the United States will be carefully limited and the rights and responsibilities of citizenship will be restricted. While the U.S. uses a logic of restriction and exclusion, it has also created specific policies to recruit migrants to work in industries where the domestic labor supply is failing. For example, the Bracero Program (1942-1965) encouraged a pattern of cyclical migration by legalizing migration for individual men working seasonally on farms. In 1965, the program was ended and the amended Immigration and Nationality Act removed all country-of-origin quotas, which led to an increase in the number of migrants coming from Latin American countries. At the same time, the U.S. government has continued to encourage the flow of migration by facilitating military and economic campaigns that destabilize Central and Latin American countries. Widespread corruption, crime, and violence are exacerbated by continuous external interference, resulting in vulnerable individuals and communities seeking out new opportunities and protection in the United States.

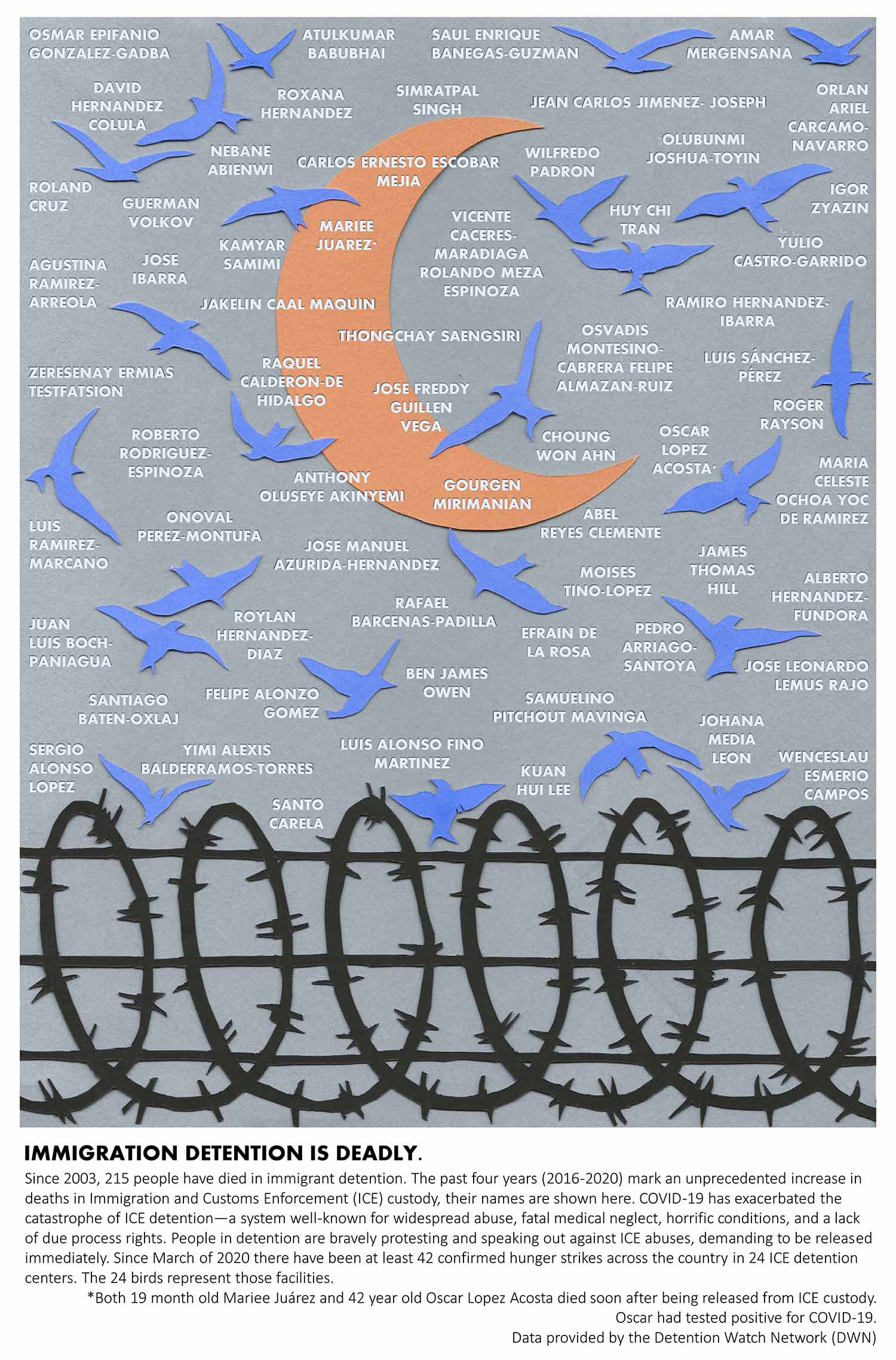

The Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986 was a major shift for immigrant communities, as it offered amnesty to millions of undocumented Mexican migrants living in the U.S. It also promised more punitive policies and restrictions for immigration moving forward. Since then, policymakers have not made any structural changes to immigration policy that facilitate pathways to citizenship or offer amnesty to undocumented workers living in the United States. Instead, politicians have focused on encouraging immigration among educated and professional immigrants, also known as “brain drain,” while providing more punitive and militarized immigrant policies, like border patrol, deportation, immigrant detention, and family separation. Pervasive immigration and anti-immigrant policies at both state and federal levels perpetuate nativist discourses of “us” versus “them,” where Latina/o/x immigrants are overwhelmingly portrayed by the media as criminals, invaders, and terrorists. This leads to an illegalized identity that can have serious ramifications. The image in 7.4.2 highlights that these ramifications are often fatal, as it memorializes the names of 215 people who died in immigration detention between 2003-2020. Hegemonic institutions, like ICE, instill fear among migrants by threatening their livelihood and family life. Further, racial profiling in immigration enforcement extends this fear to Latinx communities and people of color.

The caption on the text reads, “Immigration detention is deadly. Since 2003, 215 people have died in immigrant detention. The past four years (2016-2020) mark an unprecedented increase in deaths in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody, their names are shown here. COVID-19 has exacerbated the catastrophe of ICE detention – a system well-known for widespread abuse, fatal medical neglect, horrific conditions, and a lack of due process rights. People in detention are bravely protesting and speaking out against ICE abuses, demanding to be released immediately. Since March of 2020 there have been at least 42 confirmed hunger strikes across the country in 24 ICE detention centers. The 24 birds represent those facilities. Both 19 month old Mariee Juárez and 42 year old Oscar Lopez Acosta died soon after being released from ICE custody. Oscar had tested positive for COVID-19. Data provided by the Detention Watch Network (DWN).”

Advocates focused on immigration have used creative strategies to advance policy goals for groups who are formally excluded from political representation and legal rights in the United States. Immigrant justice movements mobilize around a range of issues that include, but are not limited to, legal reforms around immigrant rights. This takes into account the heterogeneity of immigrant communities whose concerns also include dignity, health, economic justice, and connections with mixed-status family members. While activism focused on legal rights emphasizes the state’s control over citizenship, immigrant communities also include Indigenous peoples from Latin America and advocates focused on sovereignty and cultural preservation. The range of concerns present among Latinx immigrant and Indigenous communities leads to movements that combine direct action with community support and policy change at every level (local, state, and federal).

One common issue facing both immigrant and Indigenous communities is language barriers and access. For Latinx migrant communities, access to multilingual translation and interpretation facilitates inclusion for Spanish speakers and Indigenous language speakers within Latinx communities. In California, the Mixteco/Indígena Community Organizing Project (MICOP) centralizes language interpretation in their work and lifts up Indigenous language access within networks of immigrant and health advocates. The group launched Radio Indígena in 2014, a local FM station with over 40 hours of weekly live programming, featuring at least seven Mixteco languages, Zapoteco, and Purépecha. This service provides information and entertainment that is relevant to Indigenous farm working communities, such as support for low-income individuals to receive rental assistance, energy payment programs, and family-paid leave.13 These groups put into practice a human rights framework for providing holistic support to communities. In Figure 7.4.3, an artist has depicted a family traveling in a pick-up truck accompanied by the phrase “Freedom of Movement and Family Unity are Human Rights.”

This platform served a crucial role in spreading vital public health information during the COVID-19 pandemic. They quickly expanded to include Facebook Live broadcasts to supplement radio programming and demonstrate visually how testing works and show images of how others have participated in testing. These events are interpreted in at least one Indigenous language, often through consecutive interpretation. In engaging the audience, the speakers use a conversational style. The interpreter does not just repeat the words translated from Spanish, but rather, they have coordinated in advance to share the message in a relevant way for a heterogeneous audience. For further accessibility, the videos include visual aids and photographs to guide individuals through practical steps for how to access transportation and where to arrive for testing. This visual demonstration helps to work against stigma and decrease fear of health services. The group emphasized overall health and well-being to encourage maximum prevention and safety when information about transmission was limited.

Footnotes

11 Ruth Milkman, Joshua Bloom, and Victor Narro, eds., Working for Justice: The L.A. Model of Organizing and Advocacy, Working for Justice (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2011), https://doi.org/10.7591/9780801459054.

12 Mario Alberto Viveros Espinoza-Kulick, “Movement Pandemic Adaptability: Health Inequity and Advocacy among Latinx Immigrant and Indigenous Peoples,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 15 (2022): 8981.