7.3: Queer and Feminist Chicanx Movements

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 138269

- Mario Alberto Viveros Espinoza-Kulick

- ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Confronting Patriarchy and Heterosexism in Chicanismo

🧿 Content Warning: Physical and Sexual Violence. Please note that this section includes discussion of physical and sexual violence.

Chicano identity and Chicanismo have a history of hyper-masculinity, sexism, and homophobia. These dynamics have been systematically challenged, and some of the success can be seen in the names of academic and activist groups that reflect greater gender inclusion, such as “Chicana and Chicano Studies” or “Chican@ Studies” and “Chicanx Studies.” Beyond naming, however, the structures of patriarchy and heterosexism influence movement organizations, protests, and advocacy campaigns. Men leaders often called for unity on behalf of Chicanos or La Raza, while prioritizing issues that centrally concerned men, like the draft, job discrimination, access to political power, entry into educational institutions, and community autonomy.

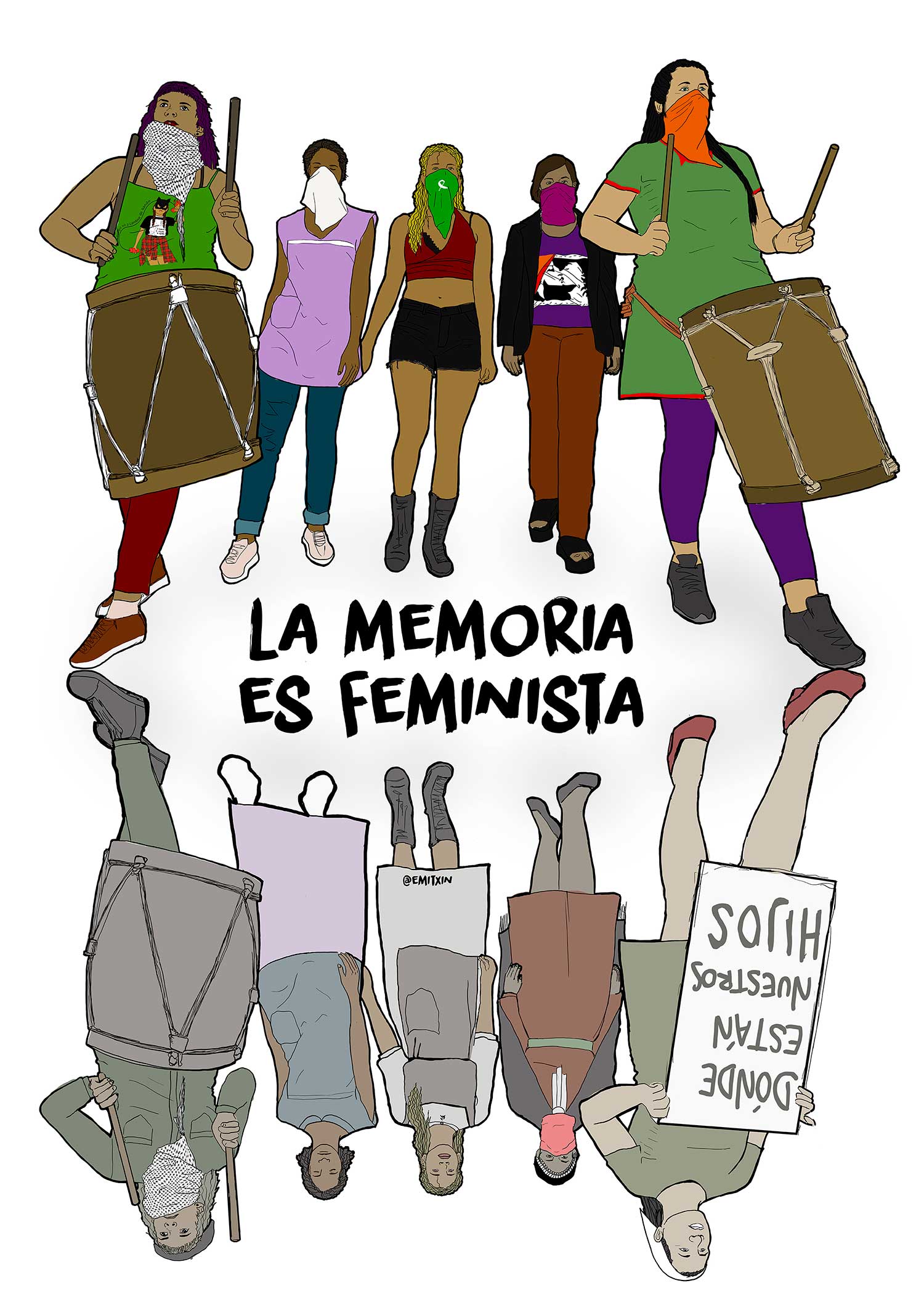

While these issues also affect women, other concerns like birth control, ending forced sterilization, welfare rights, protecting against domestic violence, and women’s sexual liberation were ignored or actively resisted by organizational leadership. “La Nueva Chicana” (The New Chicana Woman) was determined to bring these concerns together and simultaneously address systems of subordination based on both race and gender. In Figure 7.3.1, an artist has rendered a group of women marching to two drums, with their reflection showing beneath, over the words “La Memoria es Feminista" (Memory is feminist). Text on the image reads, “La Memoria es Feminista” (Memory is feminist) and one of the reflections is holding a sign that says, “Dónde están nuestros hijos” (Where are our children). This message connects current struggles for gender equality to previous ones, and also reminds us that feminism has a long history. Feminism creates new opportunities for women, and it also builds on Indigenous traditions that include matriarchal systems and other traditional ways of maintaining gender equality.

Chicana feminisms engage in political struggles for liberation and create knowledges that build coalitions across difference to mobilize consciousness and transform systems. Chicana writers and feminists reinterpreted the world for Chicanas to draw connections and develop their identities in a society that devalues women, especially women of color. This draws on distinct solidarities with Chicano men, Indigenous peoples, people of color, white women, and gender non-binary people. For instance, white feminism provides tools to discuss and analyze sexual violence and sexual pleasure, topics that are often silenced. However, Chicana experiences have to be understood and interpreted from their own intersectional standpoint. Chicanas have written about and amplified their experiences in “Chicana- and Chicano-generated newspapers, journals, and, later, anthologies, such as Aztlán, El Grito del Norte, Encuentro Feminil, and Regeneración.”8

Opposing Movement Dynamics among Chicana Women

Not all Chicanas agreed with Chicana feminists’ view that achieving gender justice was an important part of Chicanx communities’ liberation from white supremacy. Chicana “loyalists” were women in the Chicano movement that believed their place was to support Chicano men in their struggle against racialized oppression, not women’s liberation. The women often joined men in ridiculing women who sought positions of power, calling them terms like malinchistas (race traitors), and marimachas (lesbians). Leaders tried to dissuade women from voicing feminist concerns by framing the struggle as “Chicano primero,” (Chicano identity first) pitting their movement for cultural and racial heritage (“la causa”) against calls for women’s liberation.

When nearly 600 Chicana activists gathered in Houston on May 28-30, 1971 for the first National Chicana conference, La Conferencia de Mujeres Por La Raza, “loyalist” women walked out of the conference in protest over differences in political identity and goals. Ultimately, this confrontation elevated discussion about women’s issues and inspired Chicana activists to critique patriarchy and homophobia. This led to the formation of new organizations and campaigns. Adelaida del Castillo and Anna NietoGómez founded and edited the journal Encuentro Feminil at California State University, Long Beach. This became one hub of knowledge that centers the voices and perspectives of Chicana scholars and researchers. For a more in-depth exploration of these topics, visit Chapter 5: Feminisms.

Advocating for change requires sacrifice and collective support and incurs costs for those involved. Organizational structures within social movements help to fortify activists, recruit new members, train emergent leaders, and generate resources for mobilization. In particular, Chicanas and Latinas have led efforts to form and grow organizations and link social movement advocacy to existing kinship networks, family structures, and friend groups that nurture and sustain advocacy. For example, in 1970, the Comisión Femenil Mexicana Nacional (CFMN, National Mexican Women’s Coalition) was formed to address the needs of Chicanas and the issues facing women, children, families, and communities that had gone overlooked. This group was determined to provide women with the social and political capital necessary to produce social change. This led to the formation of the Chicana Service Action Center (CSAC) in 1972, as well as the Centro de Niños and League of Mexican American Women, both in 1973. These groups reflect the wide breadth of activity included under calls for “Chicana Power,” a rallying cry that’s shown in Figure 7.3.2.

Activist Spotlight: Francisca Flores

Francisca Flores is a key figure for understanding Chicanx activism. She supported and inspired Chicana feminist organizers to create organizations that focused on the intersection of race and gender. Her work helped to create new opportunities for the recognition and celebration of women’s voices. This commitment to collective effort helped mobilize Chicanas and Latinas to develop leadership consciousness and fend off the barriers created by patriarchy and sexism.

She was involved at all levels of civil rights work. As an activist in the California Independent Progressive Party and the National Progressive Party, she amplified the experiences and perspectives of Chicanas in social and economic policy debates. She was also a member of Mexican American civil rights organizations such as the Sleepy Lagoon Barrio Defense Committee in 1942; Asociación Nacional México Americana, founded in 1949; the Community Service Organization (CSO), formed in 1947; and the Mexican American Political Association (MAPA), created in 1960. Seeing that women leaders were often central to the functioning and success of these groups, she brought together other Chicanas and Latinas and they established many organizations focused on women.

Queer Latinxs Resisting Oppression

Rampant homophobia in both Chicano and Chicana activism creates a unique experience of isolation and exclusion for queer folxs, especially Chicanas. Queer Chicanas engaged in women’s liberation and queer activist spaces to build solidarities across racial lines and build community around an analysis of gender and sexuality. This included developing allies within queer communities to advance intersectional justice. Despite white, middle-class domination of these spaces, their experiences inspired intersectional mobilization and solidarity with Black queer women and other queer POC communities. Connecting with diverse queer people of color allows queer Chicanxs to work in solidarity, rather than in isolation. Queer scholars and leaders in particular used poetry and writing to influence and transform heteronormative Chicana and Chicano movements.

Gloria E. Anzaldúa was a queer Chicana poet, writer, and feminist theorist. Her poems and essays explore the anger and isolation of occupying the margins of culture and collective identity. For example, this quote from Borderlands shows her poetic interpretation of the collective identities of mexicanos:

Nosotros los Chicanos straddle the borderlands. On one side of us, we are constantly exposed to the Spanish of the Mexicans, on the other side we hear the Anglos' incessant clamoring so that we forget our language. Among ourselves we don't say nosotros los americanos, o nosotros los españoles, o nosotros los hispanos. We say nosotros los mexicanos (by mexicanos we do not mean citizens of Mexico; we do not mean a national identity, but a racial one). We distinguish between mexicanos del otro lado and mexicanos de este lado. Deep in our hearts we believe that being Mexican has nothing to do with which country one lives in. Being Mexican is a state of soul not one of mind, not one of citizenship. Neither eagle nor serpent, but both. And like the ocean, neither animal respects borders.9

While her perspective was rooted in an inclusive queer Chicana sensibility, the wisdom of her words extended far beyond this specific experience. Anzaldúa has been awarded the Lambda Lesbian Small Book Press Award, a Sappho Award of Distinction, and an National Endowment for the Arts Fiction Award, among others. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza by Gloria Anzaldúa emphasized indigeneity and mestiza identities. Similarly, This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, edited by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa “critiqued sexism, racism, classism, and homophobia in communities of color and in the larger society.”10 A picture of Anzaldua is shown in Figure 7.3.3.

While early calls for Chicano liberation operated from a narrow view of patriarchal nationalism, Chicanas and Chicanxs have challenged and transformed this project. Chicana/o/x Power is a movement and political identity that emphasizes decolonization, rejection of cultural convention, and activism over origin or language. There is no one right way to achieve liberation, but communities can work in solidarity and through organized movements to bring about justice.

Today’s movements have been deeply informed by the alliances and bridges formed by these forward-thinking activists. For example, the undocumented immigrant youth movement “borrowed” the cultural schema of “coming out” and joined it with “out of the shadows” for successful mobilization. Undocumented queer leaders were key in amplifying this framing and forging the connection between the different experiences of being socially constrained by the heteronormative expectations of “the closet” and the structural violence that places undocumented children in fear of having their immigration status used against them or their families. You can explore more topics related to queer and trans experiences and activsm in Chapter 6: Jotería Studies.

Footnotes

8 Miroslava Chávez-García, “A Genealogy of Chicana History, the Chicana Movement, and Chicana Studies,” in Routledge Handbook of Chicana/o Studies, eds. Francisco A. Lomelí, Denise A. Segura, and Elyette Benjamin-Labarthe (New York, NY: Routledge, 2018), 68.

9 Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco, CA: Aunt Lute Books, 1987), 62.