8.4: When Ganas is not Enough, 1976-2000

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 138279

- Lucha Arévalo

- ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Public Schools as Scapegoats

By the 1980s, an era obsessed with academic “excellence” was introduced. This was evidenced in the report A Nation at Risk (1983), which cautioned over a “rising tide in mediocrity” and sustained a discourse that advocated for higher standards in public schools. It is no coincidence that this report emerged at a time when the rise in foreign-born populations from Latin America and Asia gave rise to xenophobic fears and an English Only movement. At the center of these debates was the Plyler v. Doe (1975) Supreme Court case filed by the Mexican American Legal Defense Fund (MALDEF). Decided in 1983, it involved the state of Texas changing an Education Code to allow schools to withhold admission or charged tuition to undocumented children. The court ruled that every young person, regardless of their immigration status, has a right to attend a free public school in grades K-12. This historic case was essential for combating early efforts to create a school-to-deportation pipeline, that is, school policies and practices that effectuate the removal of undocumented immigrant youth from schools and ultimately the U.S.

While the removal of undocumented immigrant children in schools remained unsuccessful, language in schools continued to be a political battleground that enabled the continuance of segregation and Americanization efforts previously employed to discriminate and exclude non-native English speakers, including Latinx children. In 1986, Proposition 63 passed, which made English the official language of California.53 The xenophobic fears of the time were among many other social fears attached to crime and poverty that targeted the most vulnerable student populations in our schools.

Mr. Escalante’s Math Enrichment Program

Mainstream portrayals of urban schools as pathological, deficient, decaying, and failing were captured through popular media productions such as the iconic films, Stand and Deliver (1988) and Lean on Me (1989), which were both based on true stories. For example, Stand and Deliver focuses on Bolivian American math teacher, Jaime Escalante, from Garfield High School in East Los Angeles, who raised expectations and instilled the ganas (spirit of motivation, willpower, grit, and resilience) in his students.54 The film credits his ethic of care and strict pedagogy to the success of 18 of his students who passed their AP Calculus exams in 1982. The Educational Testing Service accused the students of cheating, made them retake the exam, and when they did they passed with even higher scores, and proved to the nation that inner city kids were teachable. While the film sheds light on the importance of educators that extend an ethic of care to their students, the truth is these students were successful because they had years of preparation and support.

The failure of Hollywood films such as these are that they do not give credit to the real source of student success. Escalante, with the support of his principal, built a math enrichment program that partnered with local feeder schools to replace basic math with algebra, giving students the opportunity to enter high school on a higher level of math. The program also partnered with the local community college to provide a 7-week intense math training course in the summer, allowing students to either get ahead or practice their skills.55 Escalante practiced an open enrollment policy for his classes, meaning anyone who was interested could take his classes, as he did not approve of gifted, honors, tracking, or the need for qualifying exams to prove they were ready. “The only thing you need to have for my program––and you must bring it every day ––is ganas.”56 The program also ensured students were provided with tutoring before and after school, and even offered paid opportunities for previous students to provide tutoring. Essentially, Escalante’s students were successful because he disrupted the status quo, created a new academic pipeline in math, and provided the support students needed to succeed.

Stand and Deliver, like many films of the time, does not accurately show why students were successful and instead credited a tough, punitive approach to schooling. Mr. Escalante knew that students needed more than ganas to succeed academically, hence he went beyond his role in the classroom to create educational opportunities that would have been absent otherwise. In an under-resourced school such as Garfield High School, Escalante went out of his way to create a pipeline of hope for student’s to succeed.

Films such as Stand and Deliver and Lean on Me gave mainstream audiences a glimpse into “urban schools” for the first time, or perhaps more correctly, schools where the majority of the student demographic was of color. The dominant narrative was that these urban schools were failing because they were ungovernable and out of control, not because they were overcrowded, inadequately resourced, and segregated. Change for these schools was only possible with the presence of an unrelenting patriarchal figure, whether it was Mr. Escalante’s unwillingness to give up on his students or the more punitive approach depicted in the film Lean on Me where the new principal, Mr. Clark, infamously expelled hundreds of “troublemakers” in a school assembly for their misconduct. After doing so Mr. Clark declares to the rest of the student body, “My motto is simple. If you do not succeed in life, I do not want you to blame your parents. I don’t want you to blame the white man. I want you to blame yourselves. The responsibility is yours.”57 The bootstraps narrative captured in this statement, that is, the idea that educational success is attainable through personal initiative, hard work, responsibility, and drive, is a common narrative in schools. Students are expected to beat the institutional odds set up against them as if individual effort was all that was necessary to overcome them.

Moreover, films of this time served to fuel the media hysteria over violent youth perceived as “super-predators” and implement zero tolerance policies, that is, punitive school measures that push out “problem students” through practices such as expulsion and suspension regardless of the severity of a student’s behavior. In the next decades, these types of practices and policies would become the norm for inner city schools, coalescing with what scholars identify as the school-to-prison pipeline––the school practices and policies that disproportionately place students of color into the juvenile and adult criminal justice system. The most under-resourced schools have the most resources funneled into creating prison-like school environments by implementing random locker and person searches, metal detectors, security cameras, security guards, and police presence. The disinvestment in the quality of life and educational opportunities for children of color in poverty, with the investment in the criminalization and surveillance efforts both in and out of school, effectively strengthen a pipeline from schools to prisons.

Sidebar

Latinx and Black youth are the most impacted by zero-tolerance policies and practices, accounting for the majority of school suspension and expulsion rates.

Pause and Reflect

In your opinion, what can schools do better or differently to challenge the school-to-prison pipeline?

The Latinx Threat in Schools

By the 1990s, it was clear that future immigrants were not coming from European countries nor were they Anglo-Protestants. The demographic changes were of concern to many political and academic conservatives who cautioned that future immigrants would be from Spanish-speaking countries, immigrants that once they arrived did not assimilate to American culture and life.58 In fact, demographers predicted that by 2025, Latinos would become the largest ethnic group in California. These concerns coincided with the economic recession in the early 1990s and growing civil unrest evidenced by the Los Angeles Rebellion of 1992. In communities with an absence of a large white population, narratives of racial conflict among children of immigrants and more established populations were repeatedly portrayed in the media. Most notably, Fox News coverage on what was commonly referred to as “Black and Mexican conflict” in schools. These type of stories sensationalized racial conflict and tension, grew concerns over crime and violence, and emerged at a time when California relied on undocumented immigrants as a scapegoat to be blamed.

Theory Spotlight: Leo Chavez's The Latino Threat Narrative

The xenophobic concerns of the time are best summarized by Latino anthropologist, Leo Chavez, in what he identifies as the Latino threat narrative––a dominant narrative reproduced in society:

-

Latinos are a reproductive threat, altering the demographic makeup of the nation.

-

Latinos are unable or unwilling to learn English.

-

Latinos are unable or unwilling to integrate into the larger society; they live apart from the larger society, not integrating socially.

-

Latinos are unchanging and immutable; they are not subject to history and transforming social forces around them; they reproduce their own cultural world.

-

Latinos, especially Americans of Mexican origin, are part of a conspiracy to reconquer the southwestern United States, returning the land to Mexico’s control. This is why they remain apart and unintegrated in the larger society.59

While there are many ways in which the narratives that Latinxs are a threat to society manifest, in California, there were two key propositions that captured how education became a site for policy makers to ease xenophobic fears, Proposition 187 and Proposition 227.

Proposition 187

In 1994, Proposition 187 was an initiative that, as its title indicated, attempted to “Save Our State.” The title alone invoked the idea that in the public’s imagination, California was a non-immigrant state that needed to be saved from undocumented immigrants, commonly racialized as “illegal aliens.” Governor Wilson made undocumented immigrants the focus of his political re-election campaign, endorsing Prop 187 and advertising a commercial that depicted undocumented immigrants running across the border from Mexico, warning viewers, “They keep coming. Two million illegal immigrants in California. The federal government won’t stop them at the border, yet requires us to pay billions to take care of them.”60 The proposition was passed with nearly 59% of voters approving the creation of a state-run citizenship screening system meant to deny undocumented immigrants state public social services, including access to public education and non-emergency health care. Moreover, the proposition would have deputized anyone that served or assisted an undocumented immigrant, including teachers and doctors. Essentially, employees of schools and hospitals would operate as immigration enforcement officers. It was estimated that 300,000 undocumented children were to be denied public education if enacted. However, the proposition was never enacted due to the successful legal challenge by MALDEF, ACLU, Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles (CHIRLA), and AAAJ (Asian Americans Advancing Justice), among others, that argued it was unconstitutional and violated Plyler v. Doe.

Film Spotlight: Fear and Learning at Hoover Elementary (1997)

The 1997 film, Fear and Learning at Hoover Elementary, directed by teacher-turned-filmmaker Laura Simons, takes us into Hoover Street Elementary to expose how Proposition 187 directly impacted the lives of students in one of the most diverse areas of Los Angeles.

The fight against Prop 187 was a true testament of communities rising up in solidarity. As African American high school student Annette Wells, co-founder of South Central Youth Empowered Thru Action (SCYEA), shouted to a crowd of 70,000 in Los Angeles, “This racist unjust government that we live in, finds some way to break us down. We need to join together in unity. It is about time we have peace within our community. Join us! Join us! We need to fight for voter education. Fight for voter registration, orale!”61 On November 2, only days before election day, over 10,000 youth across the state walked out in opposition to Prop 187. College students and labor unions, all united against the proposition. There was a strong presence and organized effort from Asian, Black, and white communities. The opposition to Prop 187 served to increase voter turnout among the Latinx community and created a generation of activists.62 Figure 8.4.1 and Figure 8.4.2 are from two demonstrations against Prop 187, the first in Fresno and the second in Los Angeles.

Figure 8.4.1: “March Against Prop 187 in Fresno California 1994” by David Prasad, Flickr is licensed CC BY-SA 2.0.

Figure 8.4.2: “Proposition 187 protest 1994-10-16” by Korean Resource Center, Flickr is licensed CC BY-ND 2.0.

Proposition 227

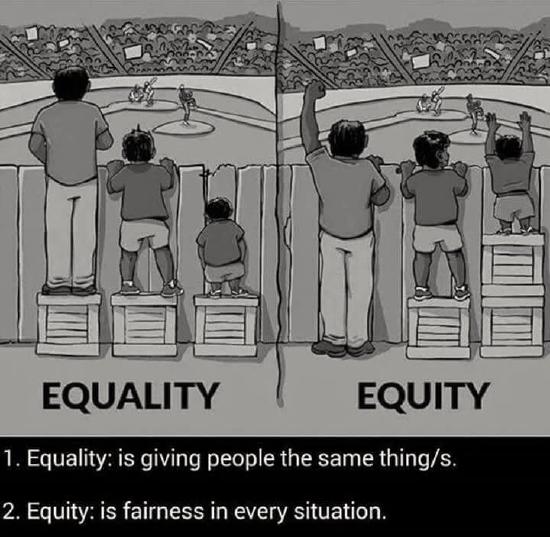

Furthermore, xenophobic fears gave way for Califonia voters to approve the 1998 Proposition 227, “English Language in Public Schools,” which effectively eliminated bilingual education in public schools and weakened language equity gains of the 1970s. Specifically, in regard to the Supreme Court decision in Lau vs. Nichols (1974) in which Chinese parents in San Francisco Unified School District filed a class-action lawsuit. The lawsuit emerged when Chinese, Filipino, and Latina/o children failed in school due to not being able to understand the lessons in English. The families essentially argued for language equity, that is, a bilingual curriculum that allowed students to comprehend and succeed. The school district counter-argued that all students were offered the same curriculum, therefore, it offered an equal education. In other words, the district asserted that offering a distinct curriculum was discriminatory as it catered to students based on their national-origin. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the parents citing that the district was in violation of the Civil Rights Act (Title IV), which meant that schools were required to create a distinct curriculum that catered to English language learners, essentially supporting bilingual education. Figure 8.4.3 illustrates the difference between equality and equity. As the image states, “1. Equality: is giving people the same thing/s. 2. Equity: is fairness in every situation.”

Figure 8.4.3: “#equality but I still don't know what banks mean by #equity” by Leigh Blackall, Flickr is licensed CC BY 2.0.

The ruling in Lau vs. Nichols is an example of why there needs to be a differentiation of equality versus equity in education. Whereas equality means that each individual or group of people are given the exact same resources and opportunities, equity recognizes that equal outcomes cannot be produced without catering to the specific needs. In this case, bilingual education was meant to address a specific need for English language learners to master the English language while retaining their native language. However, not everyone viewed bilingual education as a way for students to succeed academically. After Jaime Escalante successfully eliminated most of Garfield High School’s bilingual education classes because he believed they held students back, he served as Honorary Chairperson of the “English for the Children” campaign that sponsored Prop 227. By this time, Escalante was the most prominent Latino teacher in the state due to the appraisal of the film Stand and Deliver (1988). Escalante, like many supporters of Prop 227, argued that since language immersion programs would not exceed one year, students would master the English language faster.

However, opponents argued that Prop 227 destroys local control over language instruction for English language learners and effectively positions students to fail as they are fast-tracked to learn English in one year before transitioning to English-only classrooms. Fernando Alberto, a senior at Roosevelt High School who walked out with thousands of students across the state to protest the approval of the proposition, expressed the same sentiment exclaiming, “I don’t know where I would be if I didn’t have those classes,” referring to the bilingual classes he was placed in after emigrating from Honduras. “It’s ridiculous for them to think everyone is going to make it in just one year.”63

Sidebar

Generations of students were severely impacted by the aftermath of Prop 227. Not until 2016, did 73% of voters overturn the almost 20 year ban on bilingual instruction with Proposition 58. Today, research demonstrates that students in dual-language immersion and bilingual education students outperform traditional English-only students. California accounts for 60% of dual language programs in the U.S.

Proposition 209

The 90s was an era that blatantly attacked the Latinx community, whether it was efforts to deny undocumented students from receiving a public education or eliminate bilingual education altogether. In this era, Californian’s also witnessed institutions of higher education impacted by the Proposition 209 “California Civil Rights Initiative” (1996), which prohibits affirmative action, or granting preferential treatment based on race, sex, color, ethnicity or national origin in operating public employment, public education, or public contracting.

Affirmative action programs were essential for providing equal opportunity and diversifying colleges and universities in regard to hiring of faculty and staff, but also admissions of students. This is particularly important for underrepresented Latinx and Black students who have the lowest number of enrollment in colleges and universities. In fact, the backlash with affirmative action was a direct result of a civil rights gain in the the Supreme Court ruling of Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, which ruled in favor of university affirmative action programs, deciding that race can be one of several factors in admissions policies, but not the use of quotas. In that case, Allan Bakke was a 35-year-old white male who was denied admissions twice to the UC Davis Medical School. Bakke claimed that the special admissions reserved for minority groups excluded him based on his race. Essentially, Bakke made claims of reverse discrimination, that is, when members of dominant or privileged groups make claims of discrimination based on the rights (or in this case access) given to historically minoritized groups. Bakke claimed to be a victim of affirmative action programs designed to level the playing field for minoritized groups. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of affirmative action, but would set the waves of backlash that culminated with Prop 209.

Pause and Reflect

In 2020, Proposition 16 was placed on the ballot to repeal Proposition 209, but Californian voted against it. Do you think affirmative action programs are necessary today to provide equal opportunity in employment and education?

Starving For Justice

In the 90s, university campuses in California were called into question by the courageous leadership of BIPOC students who employed hunger strikes, literally starvation and the risk of death, as a political tactic to create social and institutional change. The hunger strikes, though not in unison or at all at once, emerged at a time when all universities experienced severe budget cuts and fee hikes, making it more challenging for BIPOC to gain access to the university and for programs such as ethnic studies to be sustained. Chicana/o Studies professor Ralph Armbruster-Sandoval’s book, Starving for Justice (2017) provides an in-depth documentation of three hunger strikes led by students at UC Los Angeles (May 24-June 7, 1993), UC Santa Barbara (April 27-May 5, 1994), and Stanford University (May 4 - 6, 1994).64 Certainly the hunger strikes were a last resort to further pressure university administrators to implement their demands for change.

In the 1990s, nearly every university campus engaged in countless protests against higher fees, budget cuts, and the university’s failure to invest in BIPOC recruitment and retention of both faculty and students. At UCSB, for example, students went on a hunger strike in 1989 and when the demands were left unmet, hunger striked again in 1994. While there were many similarities across the hunger strikes, each campus has their unique history, struggles, and set of demands. It is important to note that while the establishment and expansion of ethnic studies departments was a central concern across all of the hunger strikes, it was not the only one. In reference to the hunger strikes at UCLA, UCSB, and Stanford, professor of Chican/o studies, Ralph Armbruster-Sandoval notes, “Chicana/o studies was critical, but so were obtaining better wages and working conditions for farm workers; creating safe spaces where students and low-income immigrant families could organize and mobilize to stop budget cuts, deportations, and unscrupulous landlords; lowering student fees; and establishing a more diverse student body and faculty.”65

The strength in student power was effective because multiracial/ethnic coalitions were formed across student organizations. Students were supported by faculty who were actively engaged in the strikes, risking their own positions in doing so. The hunger strikes were effective across all of the universities in getting the administration’s attention and their commitment to implement changes. While each campus created their distinct set of demands, the self-sacrifice of hunger strikers and the communities that supported them halted the systemic demise of ethnic studies, paved the way for the university to commit to hire more faculty of color, and institutionalized the financial support for the recruitment efforts of students of color. The image in Figure 8.4.4 depicts the Third World Liberation Front 2016 hunger strikers at San Francisco State College.

Figure 8.4.4: “The Fight for Ethnic Studies_13” by Melissa Minton, Flickr is licensed CC BY 2.0.

Sidebar

The Third World Liberation Front 2016 at San Francisco State College organized a 10-day hunger strike with a list of 10 demands. To meet the demands, the collective called for the university’s investment of $8 million. As a result, there is now a Pacific Island Studies minor and faculty, two positions in Africana Studies were restored, Race and Resistance Studies was departmentalized, funding was restored to the College of Ethnic Studies, and many support programs and services for students were put into place for future generations to come.

Pause and Reflect

Why do you think students historically and today continue to take such drastic measures such as a hunger strike to enact social and institutional change?

Footnotes

53 Prop 63 was never enforced through state legislation, thereby making it unenforceable. In spite of this, the fact that 73% of voters approved the proposition is itself telling of the time.

54 For a reinterpretation of ganas as a framework see, Rebeca Mireles-Rios, Victor Rios, Bertin Solis, Jose Gutierez, “Ganas as a Praxis: Cultural Responsiveness in Latinx/a/o Higher Education Success” Studying Latinx/a/o Students in Higher Education: A critical analysis of concepts, theory, and methodologies (New York and London: Routledge, Taylor & Frances Group, 2021), pp 91–105.

55 Jerry Jesness, “Stand and Delivery Revisited,” Reason, July 2002. Last accessed October 25, 2022.

56 Jaime Escalante and Jack Dirmann, “The Jaime Escalante Math Program.” The Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 59, No. 3, (1990): 407–423.

57 John G. Avildsen, Lean on Me. (United States: Warner Bros, 1989.)

58 Samuel P. Huntington, “Hispanic Challenge” Foreign Policy Vol. 141 (2004): 30–45

59 Leo R. Chavez, The Latino Threat: Constructing Immigrants, Citizens, and the Nation (Redwood City, California: Stanford University Press, 2008) pg. 53

60 Otto Santa Ana, Brown Tide Rising: Metaphors of Latinos in Contemporary American Public Discourse (Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 2002)

61 Thirteen, “Chapter 3: Taking Action” 187: The Rise of the Latino Vote. October 6, 2020. Last accessed October 25, 2022.

62 Erick Galindo, “Brown People 25 Years Ago Created a New Generation of Activist,” LAist, November 8, 2019. Last accessed October 25, 2022.

63 James Rainey, “500 Students March Against Prop. 227,” Los Angeles Times (June 12, 1998).

64 Ralph Armbruster-Sandoval, Starving for Justice: Hunger Strikes, Spectacular Speech, and the Struggle for Dignity (Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 2017). Hunger strikes also took place at UC Irvine (October 17 - 1995), UC Berkeley (April 29- May 7, 1999), and University of Colorado, Boulder (April 19-25 1994) and Northwestern University (April 12-26 1995).