8.5: Aquí Estamos y No Nos Vamos, 2001-2012

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 138280

- Lucha Arévalo

- ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

No Child Left Behind

In 2002, Republicans and Democrats came together to pass the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB), a reauthorization of The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965, a cornerstone of the Lyndon B. Johnson administration’s efforts to carry the “War on Poverty” efforts, but this time through education. Essentially, the ESEA allows states to manage federal funds in an effort to provide an equal quality education to children in poverty. While NCLB was not the first reauthorization of the ESEA, it was different.

NCLB was a law that introduced an era of standardization and accountability in K-12 education unlike ever before. The act made the federal government’s role in education greater than ever, while allowing for schools to have local control and for parents to exercise school choice. Each public school entity was required to show adequate yearly progress (AYP) based on state-set standardized tests, with the goal that by 2014, all schools and its students were expected to perform at grade-level. The law provided federal financial support to under-resourced schools or schools classified as Title I, schools with high numbers or high percentages of low-income families, in exchange for greater accountability. In essence, the schools with the most need would get greater assistance, and all schools were expected to demonstrate AYP.

It did not take long for the results of NCLB to confirm what many critics cautioned, which is that NCLB’s unrealistic expectations will set up schools and school districts that serve historically marginalized communities to fail. In fact, a 2006 study revealed that schools that did not meet AYP in California and Illinois served 75-85% minority students, meanwhile schools that met AYP enrolled less than 40% minority students.66 Furthermore, critics stressed that state defined academic content standards and predefined achievement standards in reading/language arts and math left behind the most marginalized students, such as students with learning disabilities and English language learners, who were expected to perform at the same level of “proficiency” predetermined by the state.

The NCLB Act greatly impacted entire school cultures and school communities as they were essentially punished when they did not improve their academic performance on standardized tests. Lower performing schools prioritized teaching to the test, often with scripted lessons, and made subjects like art and history secondary as students were not tested in them.67 As a high school student in the city of Compton during this time, I recall our principal bringing a few of the AP and honors courses together to teach us how to take a test. I was blown away at how I could answer test questions for the language arts portion without actually reading the literary passage. The strategies he taught us had nothing to do with reading comprehension and more to do with test-taking skills. Our principal was willing to do what it took to excite students about the yearly testing season. He often rode a bicycle around the campus with a bubble machine to remind us, “Make sure to fill in all of the bubbles” on the test. We had pizza parties and jumpers after a long morning of testing to incentivize and reward students for attending school. While at the time I did not understand the repercussions for attending a school deemed as “failing” and “in need of improvement,” I knew that we had lost our accreditation and with it, most of our student population. These are the stories of many school communities across the U.S.

NCLB introduced an era of accountability that consequently fueled the push out of students, teachers, and in some cases, enabled the closure of public schools. What a narrow focus on standardized test outputs revealed was that the achievement gap is truly an opportunity gap that extends beyond the scope of increasing federal funds in schools. The opportunity gap refers to life chances that are determined by the lack of opportunities, which are inherently influenced by factors such as race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and ZIP code, among other social and structural conditions that prevent student readiness and better educational outcomes. None of these factors should matter, but they do. There will always be success stories of individual students that beat the odds, educators that go above and beyond, parents that become fierce advocates, community leaders that pose creative solutions, but these stories are not the norm for most students.

Militarization of Schools

A provision of the NCLB act was for military recruiters to have access to school facilities and, upon request, the contact information of each student. In other words, schools that did not comply with this provision of the federal law jeopardize receiving federal aid. Parents were given the option to opt their children out. This provision was highly criticized by students and parents alike. It opened up the question: does a military presence belong in schools? Military recruiters on school campuses are known to establish rapport with students, often serving as coaches, substitutes, and filling in where needed. Military recruitment takes place through class presentations, lunch time, and some campuses even provide a permanent office space for military recruiters to meet with students. Writing on a campaign to remove a military recruiter, Roberto Camacho summarizes:

In 2018, Truth In Recruitment helped spearhead a movement to remove a noncommissioned California National Guard recruiter who actually had an office on Santa Maria High School’s campus. Although the recruiter was officially listed as a “volunteer” who was supposed to facilitate an anti-bullying and holistic “rehabilitation” program, the office essentially served as a de facto recruitment center. Literature, pamphlets, and banners for the California National Guard were plastered both inside and outside of the recruiter’s office. A California Public Records Act request revealed that school policy dictated that volunteers could not use campus space to promote another business, and the recruiter was eventually removed. The school’s principal, however, was not happy and subsequently banned Truth in Recruitment from participating in career day events or giving presentations to students on campus.68

Educational campaigns such as those brought forth by Truth In Recruitment in Santa Maria are necessary for school communities to be self-determined in creating learning environments that reflect how they wish to experience their schools.

Many critics of military recruiters in working-class schools state that they exploit the financial and social insecurity of working-class students with the promise of a career through the military and scholarships for college. There are also issues over students’ privacy and whether the military should have access to all of a students’ contact information, especially in cases where students experience heightened military recruitment but insufficient college recruitment.

The provision in the law sparked controversy, especially because it emerged after 9/11 and the U.S. invasion of Iraq, giving way to an anti-war movement. The anti-war sentiment was strong among Santa Cruz High School students, who, at the height of the war, 300-500 students participated in a walkout in protest. This is why it was no surprise when in 2003, Santa Cruz high school students launched a campaign to adopt an opt-in policy.69 There were concerns that parents are often unaware that their child’s information was automatically shared with military recruiters. Rather than leaving the burden of opting out to parents, parents now had to opt-in to have their child’s information shared with military recruiters. The successful campaigning of students led to the district adopting this change, however, it never took effect as that summer the Department of Education and Department of Defense joined in a letter to inform all school superintendents that the “opt-in” policy is in violation of the NCLB law.

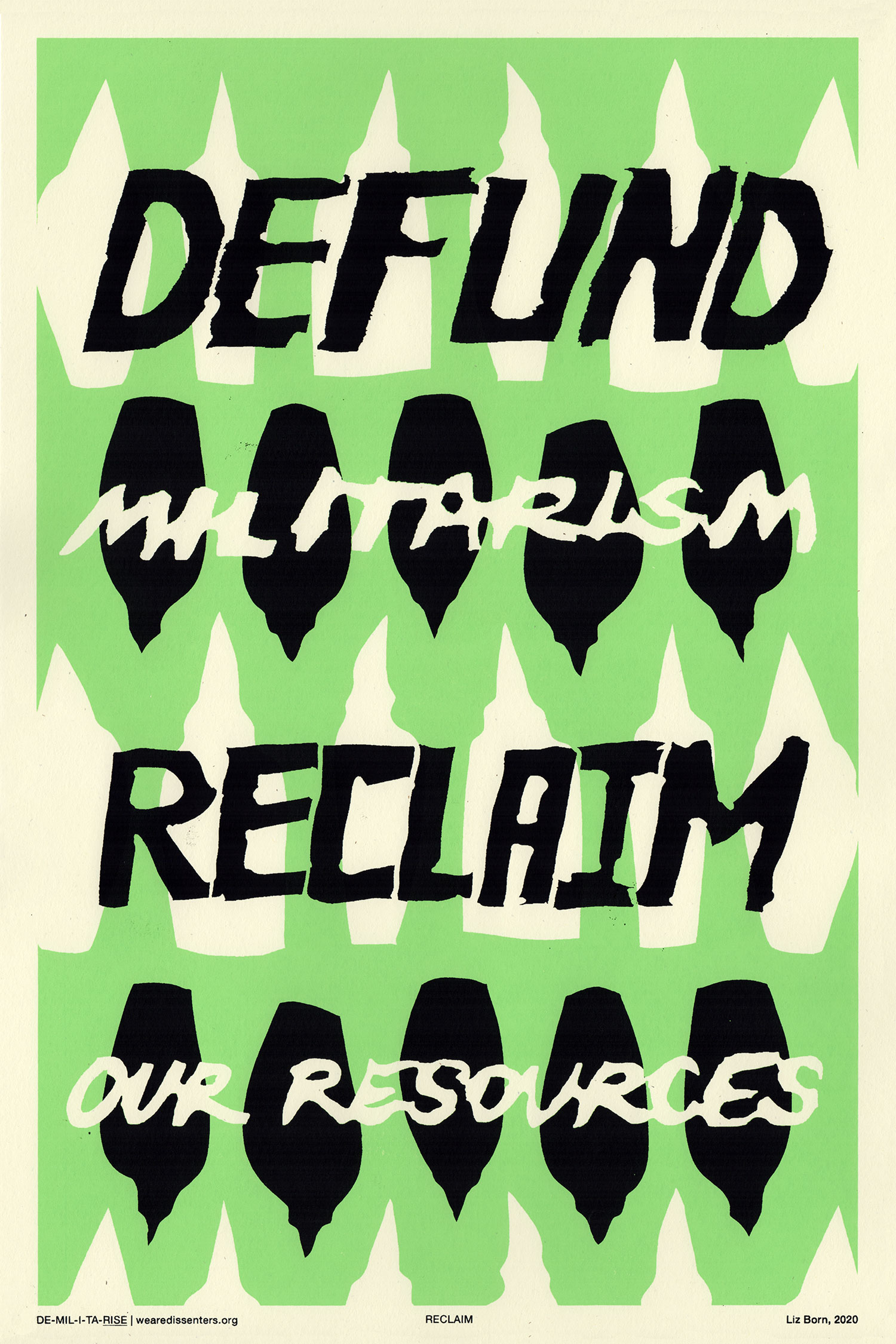

The promises offered by military recruiters is very enticing for youth who are uncertain about their future after high school. Undocumented youth, for example, are encouraged to enlist with the promise of citizenship, even though the military does not and cannot grant citizenship to its undocumented members. In fact, to enlist one needs to be a permanent resident (“green card” holder). There are, on average, 8,000 permanent residents that enlist annually. Enlisting does not guarantee a pathway to citizenship, but the military can assist its members with completing paperwork to effectuate the process. At a time when undocumented students are presented with the challenge of college affordability and access, enlisting in the military may present itself as more promising and realistic. Figure 8.5.1 displays an activist poster that reads, “Defund militarism. Reclaim our resources.” It was produced in 2020 as part of the De-mil-i-ta-rise movement to reclaim resources from the war industry, reinvest in life-giving institutions, and repair collaborative relationships with the earth and people around the world..

Sidebar

The presence of military recruiters is only one of the ways schools have become more militarized. Today, the rise of gun violence in schools has opened up the conversation on whether a stronger police presence in school is needed and some have even called for the arming of teachers and staff with guns.

Pause and Reflect

What is your opinion on military recruitment in schools and the overall militarization of schools? How do we increase campus safety?

Figure 8.5.1: “Reclaim” by Liz Born, Justseeds is licensed CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Undocumented and Unafraid

In 2001, the first version of the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act was first introduced to Congress. In short, the DREAM Act is targeted to protect current, future, and former undocumented high school graduates or GED recipients who emigrated to the U.S. as children by providing them a pathway to citizenship through college, work, or military service. For the past two decades, there have been over 10 versions of this act proposed, each time failing to garner sufficient Congressional votes to pass. In consequence, the undocumented population of over 2 million that is eligible is left deportable.

Sidebar

Annually, households that include Dreamers generate $15.5 billion in federal taxes and $8.5 billion in state and local taxes, and they hold $66.4 billion in spending power. Collectively, Dreamers own 144,000 homes and pay $1.5 billion each year in mortgage payments.70 In California, Assembly Bill 540 passed in 2001 allowing eligible undocumented students to pay in-state tuition at public colleges and universities. Since then, there have been other bills passed (AB 2000 and SB 68) that expand the scope of undocumented students eligible for in-state tuition in spite of not having resident status. While paying for in-state tuition is a great first step, it is not enough for undocumented students if they are ineligible for financial aid to assist them in paying for a higher education. In 2011, AB 130 and AB 131 were signed allowing for undocumented students designated under AB 540/AB 2000 to apply for state financial aid and state funded scholarships under the California Dream Act Application (CADAA). These reforms are critical as they allow for undocumented students financial need to be served and for them to have a sense of belonging.

Sidebar

Approximately 98,000 undocumented students graduate from U.S. high schools every year. 27,000 of those students graduate from California’s high schools.71

None of these reforms would be possible without the social unrest of undocumented students who have led and provided new directions to the (im)migrant rights movement, engaged in acts of civil disobedience, and risked arrest, detention, and deportation. Early on, the term “DREAM-er” was employed by undocumented student activists, also referred to as the 1.5 generation who emigrated to the U.S. as children. This generation identifies as American, attended and graduated from American schools, and yet are faced with institutional barriers that serve as reminders that they do not belong. Video 8.5.1 provides a glimpse into the work of Julio Salgado, an undocumented and queer (undocuqueer) activist who continues to play a pivotal role in the immigration rights movement.

Video: My Name is Julio: A Short Film By His Best Friend Jesús Iñiguez

Video 8.5.1: “My Name is Julio: A Short Film By His Best Friend Jesús Iñiguez” YouTube, uploaded by Dreamers Adrift, February 25, 2021, https://youtu.be/v9sQTMJ5axc. Permissions: YouTube Terms of Service.

This 12 minute video provides a 10 year retrospective of Julio Salgado’s artwork.

The creative genius of the undocumented student activist community was instrumental in creating awareness and mobilizing support to create change. Students wore caps and gowns and performed mock graduation ceremonies as tactics to raise awareness and redefine negative images of undocumented immigrants that depict them as criminals and unassimilated. Immigrant youth boldly affirmed they were “coming out of the shadows” and proclaiming themselves as “undocumented and unafraid.” The courage of undocumented student activists encouraged others to do the same, especially those who grew up with the understanding that no one should ever know your unauthorized immigration status. Students continue to lead reforms, such as the student organization Students for Quality Education (SQE), the signing of AB 21 in 2017, a bill to protect the information of undocumented students on CSU campuses, and to create a protocol in the event that federal immigration enforcement enters the campus.

Many colleges and universities now have a Dream Center, annual undocumented student programming, and undocumented student organizations. In spite of the gains, the fear of detention and deportation continues to be a possible reality for “DREAM-ers” and their families as none of the reforms mentioned enable a pathway to U.S. citizenship, permanent residency, nor do they assist undocumented immigrant populations that entered the U.S. as adults.

Walkouts Against HR 4437

🧿 Content Warning: Self-Harm. Please note that this section includes discussion of self-harm.

The “Border Protection, Antiterrorism, and Illegal Immigration Control Act” (HR 4437) passed the House of Representatives in December 2005 and if signed into law, it would have criminalized any undocumented immigrant without authorization to be in the U.S.. making it a felony charge. Returning from winter break, students across schools and universities expressed their opposition and organized through MySpace, text messaging, chat rooms, and email. What we collectively witnessed were nation-wide youth walkouts in hundreds of schools.

Unlike the East LA walkouts of 1968, the students who walked out in 2006 were not organizing to reform their schools from within, but to change society. Wayne Yang observed that in the Bay area, “There was no clear single leader in the student strikes, nor was there a vanguard youth organization.”72 This was true across many schools and is testament to the role that social media began to play in grassroots, organic, bottom-up youth organizing––a fast type of organizing that did not require political leadership or formal organizations. This is not to say that some schools did not have leadership, or that leaders did not emerge from the organizing.

Similar to the 1968 East LA walkouts, students were quickly reprimanded by administrators and threatened with suspension and lock downs to prevent them from walking out. At DeAnza Middle School, eight-grade student Anthony Soltero was punished for walking out by his Vice Principal, only to commit suicide later that day. As reported, the Vice Principal “terrorized” Anthony with threats of three years of prison time, forbade him from attending his 8th grade graduation ceremony, and mentioned truancy penalties his parents would have to pay for walking out.73 Anthony was already on probation for a previous offense (bringing a pen knife to school). The punitive approach taken by an administrator added unnecessary pressure to a child who was in the beginning stages of developing their own political consciousness and becoming civically engaged. It was not uncommon for students to be threatened with losing their scholarships or not being able to participate in graduation ceremonies to prevent the walkouts from continuing. Afterall, schools lose per-pupil funding when a student is marked absent and are therefore incentivized to keep students in schools. Figure 8.5.2 depicts people holding signs that honor and commemorate the life of Anthony Soltero during an anti-HR4437 demonstration, clearly conveying that these two events are connected.

Figure 8.5.2: “Continue the Struggle in Anthony’s Name” by Jim Winstead, Flickr is licensed CC BY 2.0.

What the country collectively witnessed in the spring of 2006, were a series of school walkouts to collectively express opposition to HR 4437 and support for comprehensive immigration reform and amnesty. Aquí estamos y no nos vamos (Here we are and we are not leaving) was a rallying cry across nationwide demonstrations. Students engaged in walkouts, teach-ins, and collaborated with other youth across schools and districts. Entire families participated in marches such as “A Day Without Immigrants” or The Great American Boycott, that promoted “no work, no school, no shopping” for society and industries to recognize the economic value of immigrant labor and their contributions to society. In downtown LA, we witnessed the mega-marches unlike ever before.74 Many proclaimed that the “sleeping giant” was finally awakened. The mass mobilization efforts against HR 4437 effectively prevented it from becoming law and an entire generation of students learned the collective power they have when they unite in defense of their communities.

Somos Semillas: Re-Igniting an Ethnic Studies Movement

In 2006, Dolores Huerta was invited to deliver a talk to students at Tucson Magnet High School after the nation-wide walkouts against HR4437. Upon the request of school administrators, Huerta encouraged students to explore alternate ways to create social change, such as to identify and write to their Congressional representatives and question them on why “Republicans hate Latinos.” Afterall, the anti-immigrant bills were spearheaded by the Republican party. She motivated students to continue their engagement in activism by exploring other forms of political power. This remark set off a wave of backlash by conservative Republican legislators, including Arizona’s Superintendent of Instruction of the time, Tom Horne who began probing into the school.

In “An Open Letter to the Citizens of Tucson” released in 2007, Horne began to make his case against the Mexican American Studies (MAS) program, MEChA, ethnic studies textbooks, and made a call to action for citizens to pressure the Tucson Unified School District (TUSD) to terminate ethnic studies.75 Horne’s initial strategy of mobilizing community members against the school was ineffective, and on the contrary, the entire school community along with other supporters, unified to defend what rapidly became an attack against ethnic studies in general. Horne, along with other key players, were able to get a newly elected Latino Republican state legislator, Steve Montenegro, who emigrated from El Salvador as a child, to sponsor the House Bill (HB) 2281 (2010), a revision to statute 15-112(A), which effectively sought to terminate ethnic studies.

In spring of 2010, the MAS program effectively became the target of HB 2281, which prohibited a school district or charter school from including in its program of instruction any courses or classes that:

- Promote the overthrow of the United States government.

- Promote resentment toward a race or class of people.

- Are designed primarily for pupils of a particular ethnic group.

- Advocate ethnic solidarity instead of the treatment of pupils as individuals.

This bill was passed to dismantle and ban ethnic studies programs, courses, and literature. School districts then set out to expand the list of banned books used in ethnic studies classrooms, preventing teachers from integrating ethnic studies texts into their courses.

Pause and Reflect

Examine the fourth point under Arizona’s HB 2281. In your opinion, why do you think “ethnic solidarity” was presented negatively and used to justify the elimination of ethnic studies?

The Mexican American Studies program emerged as a community-driven initiative in the late 1990s. There was a concern that Mexican American students needed a curriculum that incorporated their background and identities as a means for improving student academic achievement.76 Perhaps what was most unique about this ethnic studies program was the centering of Indigenous ancestral knowledge, epistemologies (ways of knowing), and pedagogies. The decolonial approach to learning posed a threat to the daily operation of schools and learning, as summarized by award-winning MAS literature teacher, Curtis Acosta in “Dangerous Minds in Tucson,”

Our Mexican American Studies classes were pedagogically forged to combat the passivity and acquiescence of student experiences within the status quo of public schools. Specifically, in my Latin@ Literature classes, I intentionally created educational experiences that provided spaces and time for students to reflect upon their world through the lens of the literature we studied in class. This practice, which was based upon indigenous epistemologies from our local community and cultural context, provided the foundation to build, not only an authentic classroom curriculum and climate where the students could analyze the experiences in their world, but also an immediately disrupted traditional school hierarchy through the organic injection of student voice as the initial step toward the rigorous study of literature. Through weekly journaling, casual classroom sharing, as well as formal presentations and discussions, student voice was consistently valued and normalized in the educational experiences of MAS classes.77

The program was a proven success. MAS students outperformed students not in the program when it came to reading, writing, and graduation rates. In spite of the program’s success, the state of Arizona spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to discredit and eliminate it. The state went so far as to contract Cambium Learning Incorporated to conduct an independent curriculum audit in the spring of 2011. The results of the audit only served to reinforce the effectiveness of the program and proved that the curriculum was not in violation of Arizona’s revised statutes 15-112(A). Furthermore, during this time Christine E. Sleeter (2011) documented an extensive research overview on the academic and social value of ethnic studies in schools and universities.78 As the movement in support of ethnic studies grew, so did the role for research in ethnic studies at every level of education and in the areas of curriculum, pedagogy, and policy. In spite of the extensive research positively supporing why ethnic studies is beneficial to all students, especially students of color, Arizona moved forward with the implementation of HB 2281.79

It is no coincidence that the same year HB 2281 presented its attack against ethnic studies, Arizona’s Governor Jan Brewer signed another controversial bill, Senate Bill 1070 “The Support Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act.” This policy was the strictest anti-immigration law in contemporary history, calling for the implementation of legal racial profiling in Arizona allowing law enforcement to question the immigration status of anyone stopped, detained, or arrested for a possible state violation. It criminalized any undocumented immigrant who could not provide the appropriate documentation with a misdemeanor crime and criminalized seeking employment without authorization. While SB 1070 and HB 2281 were ultimately ruled unconstitutional in court, the devastation caused by these attacks on Arizona’s youth in regard to mental health and communities altogether cannot be underestimated.

Sidebar

In 2017, a federal district judge ruled HB 2281 unconstitutional, arguing that the law was enacted with “racial animus” and used “discriminatory ends in order to make political gains.” The ban on ethnic studies in Arizona sparked a movement for ethnic studies in California.

California activists, including many educators and students, protested against Arizona’s SB 1070 and HB 2281. Across campuses, students organized demonstrations of all types– whether they were teach-ins, marches, boycotts, even caravans to Arizona– this outpour of solidarity was powerful. For many involved in these protests, including myself, it served as a reminder that while we were fighting to save ethnic studies in Arizona, in California, the number of ethnic studies courses available to high school students was small and in most cases non-existent. The sense of defeat from Arizona’s racist and xenophobic laws were transformed into an opportunity to re-ignite the fight for ethnic studies in California. In the aftermath, the formation of conferences, summits, campaigns, and institutes devoted to teaching and organizing ethnic studies grew stronger each year. The movement for ethnic studies in California continues to be a force to be reckoned with. For an overview of the growth and institutionalization of ethnic studies, review Section 1.2: Struggles and Protest for Chicanx and Latinx Studies. What we are witnessing today is the contemporary civil rights movement in education, and the enduring fight for ethnic studies is at the forefront. As the Mexican dicho (saying) reminds us, “Quisieron enterrarnos, pero se les olvido que somos semillas” (They tried to bury us. They didn’t know we were seeds). Like the students of yesterday, the students of today will continue to pave the way for generations to come.

Pause and Reflect

What is the state of ethnic studies today? What new laws, policies, and practices do you observe in support of and/or against ethnic studies? What is the state of ethnic studies on your campus?

Footnotes

66 Ann Owens and Gail L. Sunderman, School Accountability under NCLB: Aid or Obstacle for Measuring Racial Equity? (Cambridge: Civil Rights Project at Harvard University, 2006)

67 Wayne Au, “High-Stakes Testing and Curricular Control: A Qualitative Metasynthesis,” Educational Researcher Vol. 36, No. 5 (2007): 258–267.

68 Roberto Camacho, “Marginalized students pay the price of military recruitment efforts,” Prism, April 18, 2022. Last accessed October 25, 2022.

69 Rebecca Patt, “By Any Means Necessary,” MetroActive, March 2003. Last accessed October 25, 2022.

70 Nicole Prchal Svajlenka, “The Dream and Promise Act Put 2.1 Million Dreamers on Pathway to Citizenship,” American Progress, March 26, 2019. Last accessed October 25, 2022

71 Jie Zong and Jeanne Batalova, “How Many Unauthorized Immigrants Graduate from U.S. High Schools Annually?” Migrant Policy Institute, April 2019

72 K. Wayne Yang, “Organizing MySpace: Youth Walkouts, Pleasure, Politics, and New Media,” Educational Foundations (Winter-Spring 2007): 17.

73 Favianna Rodriguez, “Death By Suicide,” (blog), April 10, 2006 (Last accessed October 25, 2022).

74 Alfonso Gonzalez, Reform without Justice: Latino Migrant Politics and the Homeland Security State, (Oxford University Press, 2013)

75 Tom Horne, “An Open Letter to the Citizens of Tucson,” State of Arizona Department of Education, June 11, 2007.

76 To read more about the formation of the program, see Conrado Gomez and Margarita Jimenez-Silva, “Mexican American Studies: The Historical Legitimacy of an Educational Program” Association of Mexican-American Educators (AMAE) Journal Vol. 6, No. 1 (2012): 15–23.

77 Curtis Acosta, “Dangerous Minds in Tucson: The Banning of Mexican American Studies and Critical Thinking in Arizona,” Journal of Educational Controversy, Vol. 8, No. 1, Article 9 (2012): pg. 9.

78 Christine E. Sleeter, “The Academic and Social Value of Ethnic Studies: A Research Review,” Washington, DC: National Education Association, 2011.

79 For an introduction to curriculum, pedagogy, and research in ethnic studies see, Christine E. Sleeter and Miguel Zavala, Transformative Ethnic Studies in Schools: Curriculum, Pedagogy, and Research, (Teachers College Press, 2020).