9.1: Frameworks for Analyzing Chicanx and Latinx Health

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 138282

- Mario Alberto Viveros Espinoza-Kulick & Melissa Moreno

- ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Conceptual Tools for Understanding Chicanx and Latinx Community Health

There is much health and healing of body, mind, and spirit to do given our Chicanx and Latinx history of genocide, colonization, violence, acculturation, sterilization, hazardous working conditions, environmental toxins, diabetes, intergeneration trauma, abuses, and more. Views of health are shaped by one's culture, and culture is informed by nationality, ethnicity, class, gender, sexuality, language, and dis/ability.1 At the same time, health access and health resources are historically and negatively impacted by a history of anti-Indianness, racism, classism, undocumented status, and region.2 The implications of wealth, or net worth (what you own minus what you owe) by race, home ownership, and neighborhood income is apparent in the health inequality and lack of health access. There are often better health facilities and well-trained doctors and fully staffed medical facilities in more affluent communities compared to poor ones. For this reason, the emergence of community-based clinics has been critical to racialized ethnic communities, especially in California Chicanx and Latinx communities.3

Think about your own experience with health and healing and that of your parents and grandparents. Where have they received most of their health and healing information? Both institutional and traditional health care are key to our communities. Institutional health care has to do with health care provided by hospitals and with doctors, physicians, prescribed medications, surgical procedures, and psychiatric appointments, which typically involve insurance. Traditional health care has to do with Indigenous ways of health and healing of cuerpo y alma (body and soul) mediated through curanderas/os (healers) or other specialists, like parteras (midwifes) and involves remedios (medicinal herbs), ceremonies, limpias (spiritual cleansings), sobaradoras/os or sobadas (massage therapist or massage), huezeras/os (bone setter), informal counseling for bilis (rage), susto (fright), or envido (envy), ancestral foodways, and referrals to medical doctors if needed.4 Traditional health care has been in existence since before colonization and requires skilled and experienced healers.

There are a number of pathways that influence the relationship between settler-colonialism, white supremacy and health. These include the types of foods we eat and what kinds of foods are available for consumption, as well as the environments in which communities live, work, and raise families. These examples show how settler colonialism and white supremacy operate to reproduce health disparities and the ways that communities contest these systems through resilient communities and collective resistance.

Traditional Health Practices and Perspectives

In recent years, with an alarming rate of cancer and research on the connection between our gut and minds, there has been an attempt to move away from processed foods and move towards decolonizing diets and cultivating gardens.5 This means moving towards the use of ancestral foodways, which includes Mesoamerican (Anaucan) super foods like corn, beans, squash, nopales (cactus), chiles, amaranth, and chia and regarding food as an essential part of health and healing rather than only for consumption. However, Chicanx and Latinx communities are more likely to have a hard time accessing fresh fruits and vegetables. In many low-income and immigrant communities, few stores and markets sell fresh items compared to alcohol and processed foods within approximate distance to homes. This can result from zoning processes that place low-income residences and immigrant worker housing in areas far away from central commercial areas and restaurants. Chicanx and Latinx farmworker families who work in the food industry and provide sustenance for communities around the globe are often directly impacted by these disparities.

In terms of abortion, there are various understandings and stances in Latinx communities. Historically among some Chicana/x and Latina/x Indigenous women, there is an awareness of herbs (ruda, etc.) and teas that are believed to terminate a pregnancy under the direction of a healer and seriously considering the context of a woman. Given the understanding of the importance of body, mind, and spirit and deep connection to cosmology, abortion is viewed by some healers as a sacred decision that can only be made with much prayer or meditation for permission from the cosmos or divine universe. In a traditional approach, the decision to undergo an abortion requires healing and asking for forgiveness specifically of the uterus because it is viewed as the living organ in which the spirit of the aborted needs to be acknowledged before letting go. There is the healing of the uterus as well as the emotional healing for mental health. A ceremony of healing for loss is needed, requiring prayers in a circle of women who understand life, death, and regeneration, as well as the connection of body, mind, and spirit. On the other hand, the conversation and practice of abortion for Chicanas/xs and Latinas/xs in the context of Christian and Catholic households is sometimes filled with stigma, shame, and embarrassment. Making the decision and undergoing the medicalization of abortion in isolation or secrecy, without the support of mothers or family members, sometimes poses challenges to health and healing in the body, mind, and spirit.

In “To Valerse Por Si Misma between Race, Capitalism, and Patriarchy: Latina Mother-Daughter Pedagogies in North Carolina,” Sofia Villenas and Melissa Moreno examined the narratives or conversations and oral life histories of a group of Latina mothers focusing on the teaching and learning that occurs between mothers and daughters on gender and sexuality through consejos (advice), cuentos (stories) and la experiencia (experience), which are filled with tensions and contradictions yet open with spaces of possibility. Latinas evoked patriarchal ideologies about being a mujer de hogar (woman of the home), while simultaneously negotiating these in discourses about knowing how to valerse por si misma (to be self-reliant). Mothers teach daughters to be submissive, rebellious, and conforming, all at the same time, as they maneuver between race, patriarchy, and capitalism in the United States.6

Traditional health through an Indigenous framework acknowledges the connection and health between body, mind, and spirit. Another example of Indigenous health practices is in the realm of birthing, which is typically regarded as a ceremony, where mothering is considered to be a state of reverence and sacredness as mothers bring life into the world.7 The guidance of a midwife and doula is valued. You can learn more about the diverse perspectives of midwives of color at this blog site. Indigenous labor practices can involve birthing while squatting, holding on to someone, or using a rebozo (traditional shawl) to be held up rather than laying on a bed. Postpartum, the healing after birthing, is thought to require la cuarentena, forty days of rest to restore body, mind, and spirit. Specifically restoring the uterus from birthing the child is important. This can include the use of eating and drinking only warm food elements for one’s body and steady milk production. It can also include using a rebozo or faja (girdle) around the abdomen for support and receiving proper and gentle massages. In terms of connection, there is a family ritual of burying the umbilical cord in a special place where a child can return for a sense of connection and belonging when and if needed in their cycles of life. During newborn stages, the baby is swaddled tightly in the hope of providing comfort similar to in-utero and slow integration into the outside world.

Although there are generations of scientific, religious, and cultural knowledge embedded in traditional health practices, these perspectives are often disregarded in the face of dominant western healthcare. The positive value of these practices depends on the continued health and vitality of the communities that carry them forward.

Healthcare Access and Institutional Health

Traditional remedios or medicinal herbs and ancestral foodways for the people connected to land have been impacted by invasion and colonization by the Spanish and European Americans beginning 500 years ago to 150 years ago, depending on the region in this hemisphere, and continuing to today through the structure of settler-colonial governments.8 When people are de-territorialized or displaced, they lose their land and access to remedios (medicine) and ancestral foodways. In combination with settler-colonialism, industrialized capitalism has led to the increased production and sale of processed foods. When you lack access to ancestral food and shift to more processed foods, the increase in sugar, lard, and other chemicals leads to an increase in diabetes and other related health conditions. Diabetes, in some cases, is caused by the experience of being torn from ancestral food and shifting into colonized foodways.9

Acculturation refers to the process of adapting to and adopting cultural practices of a new environment, which can include both individual change and community and cultural change. In the context of Chicanx and Latinx health, acculturation is often measured through the number of generations one’s family has lived in the United States. Acculturation is associated with many important health outcomes, including diabetes, obesity, negative birth outcomes, and substance abuse.10 This can be attributed to the stress that occurs for Chicanx and Latinx families, which includes systemic barriers in housing, education, and employment, as well as bias and discrimination against immigrants. This can impact health outcomes at the community, individual, physiological, and cellular levels.11

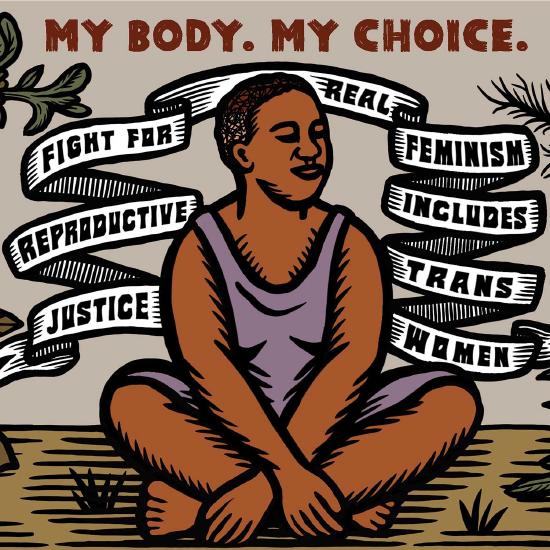

Institutional health care has contributed to a range of injustices and health disparities. For Chicana/x and Latina/x, Native American, and Black women there is a history of reproducing injustice dating back to colonization and slavery.12 In the early 1900s, the Eugenics Movement mobilized racist theories of intelligence that also enabled the practice of forced sterilization. For more details on this topic, you can review Section 5.3 on Reproductive Justice. It impacted family formation and served as a form of population control. This history of medical violence experienced by women of color, including Chicanas/xs, Puertorriqueñas/xs, and Latinas/xs continues to cause harm in the lives of people who were not able to have children and entire communities who avoid or delay care due to mistrust of medical providers.13 In Figure 9.1.1, there is an activist poster from the Women’s Conference in Houston, Texas which leads with the popular reproductive rights framing, “My Body. My Choice,” along with the statements, “Fight for Reproductive Justice” and “Real Feminism Includes Trans Women” around a brown woman sitting in a meditative position.

Accessing institutional health requires health insurance or large out-of-pocket payments. Both of these can be prohibitive for low-income communities, immigrants, and communities of color like Chicanxs and Latinxs. As well, language barriers can play a role in the struggle for health access. In some Latinx communities, bilingual or Spanish-speaking promotoras are essential to helping community members navigate the health system and receive care.14 Promotoras are health workers who have received specialized training to provide basic health education in the community, who have been key mediators for Chicanx and Latinx communities to gain health access. You can learn more about how promotoras have been part of saving lives and caring for communities with HIV/AIDS in Chapter 6.

The lack of clean and safe water and toxic pollutants used on crops compounds health issues and avoidable illnesses. The impacts of contemporary food systems on our bodies, minds, and spirit have been detrimental. Historically groups like the United Farmworkers, American Indian Movement, Black Panther Party and the South Central Los Angeles Farm have raised awareness about this reality concerning food access and insecurity in Chicanx, Latinx, and Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities. Food is ultimately important to forming healthy families and communities. In response, more and more farmers' markets are emerging in low-income working-class communities, aided by the ability to accept EBT payments (food stamps).

Oftentimes, traditional food and food cultures of people of color are characterized as unhealthy, without regard to their place in spiritual, physical, and social processes. For example, outside observers may not understand that certain dishes are meant for holidays, special occasions, and family gatherings. While they may build from the same staple ingredients within the diet, daily dishes are often more modest. In the most extreme distortions, Americanized versions of Chicanx and Latinx foods with processed ingredients, extreme portion sizes, and unhealthy additives are taken to stand in for traditional foods.

In some contexts, researchers have observed a pattern that can be described as the Latino Health Paradox. This means that immigrant Mexican and Latinx people report better health and longer life expectancy compared to their acculturated Mexican origin and Latinx counterparts as well as European Americans, includcing those of higher class statuses. Despite experiencing discrimination and institutional exclusion, which are typically risk factors that exacerbate bad health, recent migrants carry forward strong traditions of resilience and well-being. Traditional diet and lifestyle play a major role in the Latino Health Paradox theory. Fewer years of processed foods, more walking, and less drug and substance abuse by immigrants make a difference in everyday health and overall longevity.

Institutional health has been structured around the role of doctors exclusively tending to the physical body. This perspective is supported by western medicine and, in the U.S. context, involved with the for-profit pharmaceutical and health insurance industries. However, there has also been a movement towards holistic medicine that has found supporters in hospitals and clinics, including formal partnerships with traditional healthcare providers. For example, certified midwives have only recently been accepted to work in hospital settings in the state of California since 2010. Nursing and breast milk have recently been valued compared to the once popular formula and commercialized milk. Some hospitals have an option for birthing in water. Some physicians have improved care for transgender and other vulnerable communities. For supplemental exploration on this topic, explore this short post from UC Davis on the topic of transgender care.

Holistic health practitioners and traditional health perspectives recognize the need to radically shift the current medical system of health services to a commitment to healthcare for all. The image displayed in Figure 9.1.2 visualizes the activist call for “Health Care For All!”

Figure 9.1.2: “Healthcare for All” by Josh MacPhee, Justseeds is licensed CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Disability Justice among Chicanx and Latinx Communities

Disability justice and the health of the Chicanx and Latinx community are interconnected in several ways. The principles of disability justice emphasize the rights and inclusion of individuals with disabilities, recognizing that disability is not solely an individual issue but a result of societal barriers and systemic oppression. In the context of the Chicanx and Latinx community, this means acknowledging and addressing the unique health challenges faced by individuals with disabilities within these communities.

Chicanx and Latinx communities often faces disparities in access to healthcare, which can further impact individuals with disabilities. Limited resources, language barriers, and cultural factors can hinder their ability to receive adequate healthcare services and support. Disability justice advocates for a comprehensive approach to health that addresses these barriers and ensures that healthcare systems are inclusive, culturally sensitive, and accessible to individuals with disabilities within the Chicanx and Latinx community. This includes promoting awareness and education about disability rights, advocating for equal healthcare access, and creating support networks that prioritize the well-being and needs of individuals with disabilities in these communities. By integrating disability justice into Chicanx and Latinx community health initiatives, we can work towards a more equitable and inclusive healthcare system that promotes the overall well-being of all community members.

Footnotes

1 Angie Chabram-Dernersesian and Adela de la Torre, eds., Speaking from the Body: Latinas on Health and Culture (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2008); Adela de la Torre and Antonio Estrada, Mexican Americans and Health: ¡Sana! ¡Sana!, 2nd edition (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2015); Yvette G. Flores, Chicana and Chicano Mental Health: Alma, Mente y Corazón (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2013); Rose M. Borunda and Melissa Moreno, Speaking from the Heart: Herstories of Chicana, Latina, and Amerindian Women, 3rd edition (Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt Publishing, 2022).

2 Edna A. Viruell-Fuentes, Patricia Y. Miranda, and Sawsan Abdulrahim, “More than Culture: Structural Racism, Intersectionality Theory, and Immigrant Health,” Social Science and Medicine, 75, no. 12 (December 1, 2012): 2099–2106, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.037.

3 Castulo De la Rocha, Diana M. Bonta, and Jose J. Garcia. The Chicano Boom: Healing California 1965-19865 (Los Angeles, CA: Alta Med Health Services, 2019).

4 Elena Avila and Joy Parker, Woman Who Glows in the Dark: A Curandera Reveals Traditional Aztec Secrets of Physical and Spiritual Health (New York, NY: Penguin Putnam Inc., 2000); Flores, Chicana and Chicano Mental Health; Brian McNeill and Jose M. Cervantes, eds., Latina/o Healing Practices: Mestizo and Indigenous Perspectives (New York, NY: Routledge, 2011); Bobette Perrone, Henrietta H. Stockel, and Victoria Krueger, Medicine Women, Curanderas, and Women Doctors (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1989); Jerry Tello, Recovering Your Sacredness (Hacienda Heights, CA: Sueños Publications LLC, 2019).

5 Luz Calvo and Catriona Rueda Esquibel, Decolonize Your Diet: Plant-Based Mexican-American Recipes for Health and Healing (Vancouver, Canada: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2015); Devon Peña, Luz Calvo, Pancho McFarland, and Gabriel Valle, eds., Mexican-Origin Foods, Foodways, and Social Movements: Decolonial Perspectives (Fayetteville, AK: University of Arkansas Press, 2017).

6 Sofia Villenas and Melissa Moreno, “To Valerse Por Si Misma between Race, Capitalism, and Patriarchy: Latina Mother-Daughter Pedagogies in North Carolina,” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 14, no. 5 (2001): 671–87.

7 Lara Medina and Martha R. Gonzales, eds., Voices from the Ancestors.

8 Roberto Cintli Rodríguez, Our Sacred Maíz Is Our Mother: Indigeneity and Belonging in the Americas (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2014); Elisa Facio and Irene Lara, eds., Fleshing the Spirit: Spirituality and Activism in Chicana, Latina, and Indigenous Women’s Lives (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2014); Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants (Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions, 2015); Brian McNeill and Jose M. Cervantes, eds., Latina/o Healing Practices: Mestizo and Indigenous Perspectives (New York, NY: Routledge, 2011); Lara Medina and Martha R. Gonzales, eds., Voices from the Ancestors: Xicanx and Latinx Spiritual Expressions and Healing Practices (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2019); Eliseo Torres and Imanol Miranda, Curandero: Traditional Healers of Mexico and the Southwest (Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt Publishing, 2017).

9 Leslie O. Schulz, Peter H. Bennett, Eric Ravussin, Judith R. Kidd, Kenneth K. Kidd, Julian Esparza, and Maruo Valencia. “Effects of Traditional and Western Environments on Prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes in Pima Indians in Meixco and the U.S.” Diabetes Care 29, no. 8 (2006): 1866–1871. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc06-0138

10 Marielena Lara, Cristina Gamboa, M. Iya Kahramanian, Leo S. Morales, and David E. Hayes Bautista. “Acculturation and Latino Health in the United States: A Review of the Literature and its Sociopolitical Context.” Annual Review of Public Health 26 (2005):367–397. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615

11 Rosa M. Gonzalez-Guarda, Allison M. Stafford, and Jamie L. Conklin. “A Systematic Review of Physical Health Consequences and Acculturation Stress among Latinx Individuals in the United States.” Biological Reserach for Nursing 23, no. 3 (2021): 362–374.

12 Elena R. Gutiérrez, Fertile Matters (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2008), http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7560/716810.

13 Ellen Bass and Laura Davis, The Courage to Heal: A Guide for Women Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse, 20th Anniversary Edition, 20th Anniversary ed. (New York, NY: William Morrow Paperbacks, 2008); Gutiérrez, Fertile Matters.

14 Natalia Deeb-Sossa, Doing Good: Racial Tensions and Workplace Inequalities at a Community Clinic in El Nuevo South (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2013).