9.2: Mental Health

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 138283

- Mario Alberto Viveros Espinoza-Kulick & Melissa Moreno

- ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

Prevalence of Mental Health Conditions

🧿 Content Warning: Self-Harm and Physical Violence. Please note that this section includes discussion of self-harm and physical violence.

Latinxs demonstrate variability in the prevalence of mental health disorders.15 In 2018, 8.6 million Latinx adults had a mental health or substance use disorder.16 While this is a substantial burden of mental health issues, evidence also suggests that Latinx individuals experience a lower risk of most mental health disorders compared with non-Latinx white individuals, which means that we can learn about important protective factors by examining the practices of Chicanx and Latinx groups. However, U.S.-born Latinxs report higher rates for most psychiatric disorders compared with Latinx immigrants.17 Latinxs may identify with different racial categories, immigration experiences, languages spoken, and more, but all Latinxs share a common experience of family origin in Latin America.18

Latinx youth are at particular risk of mental health disorders: among Latinx high school students, 18.9% had seriously considered attempting suicide, 15.7% had made a plan to attempt suicide, 11.3% had attempted suicide, and 4.1% had made a suicide attempt that required medical attention.19 Furthermore, Latinx youth report a higher prevalence of illicit substance use and initiation of alcohol or cigarette use in the past year relative to youth belonging to other racial/ethnic groups.20

Factors Impacting Chicanx and Latinx Mental Health

🧿 Content Warning: Physical and Sexual Violence. Please note that this section includes discussions of physical and sexual violence.

Several mutually constitutive and overlapping factors contribute to the development of mental health disorders in Latinxs. Latinxs, particularly those who have migrated to the U.S., report high rates of trauma. Migration, or transnational mobility, entails multiple vulnerabilities, including violence and economic precarity in one’s country of origin; threats or risks of physical and sexual violence, dehydration, kidnapping, and exploitation during border crossings; family separation; and detention and deportation.21 Experiences are particularly harrowing for women, who may confront rape, forced prostitution, trafficking, and physical violence.22 Reports of trauma exposure are extremely high among Latina migrant women, with prevalence rates around 75%.23 In addition, many Latinxs carry historical trauma relating to European colonization, enslavement, sexual violence, and genocide of Indigenous peoples of the Americas.24 Such reproductive and genocidal violence continues with reports of recently coerced hysterectomies on (im)migrant women detained in Georgia.25

Discrimination, Exclusion, Violence, and Health

🧿 Content Warning: Physical Violence. Please note that this section includes discussions of physical violence, including violence against people of color by police and immigration enforcement.

Latinx migrants and their descendants experience discrimination. Both acculturative stress and discrimination have been shown to impact physical health through the mediating effects of anxiety.26 For example, greater experiences of discrimination moderate the effect of harsh working conditions, increasing symptoms of anxiety and depression among migrant farmworkers in the rural Midwest.27

Restrictive immigration policies and enforcement contribute to psychosocial stress among Latinxs. Increased immigration enforcement is associated with higher mental distress and decreased self-reported health.28 There are consistent associations between restrictive immigration policies and outcomes including depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).29 Similarly, citizen children who worry about losing a caregiver suffer from higher rates of depression, anxiety, emotional distress, and hypervigilance.30 Among pregnant women, fear of deportation and fear of a family member being deported are associated with higher prenatal and postpartum anxiety.31 For example, following the implementation of 287(g) agreements, which permit the cooperation of federal immigration authorities with local police, pregnant Latina women sought prenatal care later and had inadequate care when compared with non-Latina women.32 One study found that a 1% increase in a state’s immigration arrest rate was significantly associated with multiple mental health morbidity outcomes.33 In the wake of immigration raids and mass deportations, (im)migrants and Latinxs in particular report greater stress and fear and worse health.34 Many activists have worked to actively contest these fears. One example of this is shown in Figure 9.2.1, which displays an image of two Latina activists, holding a sign that reads, “End SB 1070 and Family Separation,” referring to to Arizona’s Senate Bill 1070 that authorized widespread racial profiling against Latinxs and immigrants. The scene is accompanied by the words, “Nos Tienen Miedo” and “Porque No Tenemos Miedo,” which translates into English as “They are afraid of us, because we are not afraid.”

Figure 9.2.1: "Nos tienen miedo porque no tenemos miedo" by Jesus Barraza, Justseeds is licensed CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

These latter findings are particularly relevant amid intensifying anti-immigrant sentiment and increased deportation in recent years. In 2016, within days of his inauguration, former President Trump signed Executive Order 13768 entitled “Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States,” which expanded deportation priorities to effectively include every undocumented (im)migrant, promoted increased use of state and local police to enforce federal immigration law through section 287(g) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (i.e., 287(g) agreements), and directed the hiring of 10,000 Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers.35 Following this order, an additional 52 jurisdictions signed 287(g) agreements. In addition, the Trump administration attempted to revoke temporary protected status from individuals who emigrated from Nicaragua, Haiti, and El Salvador; however, this effort was stymied by the Ramos, et al. vs. Nielsen, et al. decision of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California.36 The administration also enacted a Zero Tolerance Policy with respect to unauthorized immigration, prosecuting (im)migrants as criminals, detaining them in hieleras (ice-cold cells) and separating children from their parents at the border. The subsequent Biden administration has begun to counter some of these policies; however, even by their own admission, this is a lengthy political process. Beyond that, the harsh policies enacted by the Trump administration have a lasting impact, even as they are dismantled at the federal level. State and local activists have also continued to mobilize around similar policies, including the building of a border wall in Texas.

Structural Vulnerability and Health Disparities

Structural vulnerability—or an individual’s “location in their society’s multiple overlapping and mutually reinforcing power hierarchies (e.g., socioeconomic, racial, cultural) and institutional and policy-level statuses (e.g., immigration status, labor force participation)”37—conditions mental distress and inadequate access to care. Among migrant farmworkers, harsh working conditions significantly predict symptoms of anxiety and depression.38 Under the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA), permanent residents are ineligible for public assistance during their first five years in the U.S. The public charge rule, a broader interpretation of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) § 212(a)(4), states that individuals are inadmissible to the U.S. if they are “likely at any time to become a public charge” and has discouraged noncitizens from pursuing needed benefits prior to regulating their status.39 Although the Biden administration has repealed the changes to this policy made during the Trump administration, fear persists among immigrants who are eligible to access services. In addition, due to their explicit exclusion from the Affordable Care Act, undocumented (im)migrants have almost no access to public health insurance as well as limited options for employer-based or private insurance.40

This structural vulnerability contributes to barriers in accessing mental health care. Nationally, Latinxs have the highest uninsurance rate of any racial/ethnic group, at 29.7%.41 Only 1 in 10 Latinxs with a mental disorder receive mental health services from a general healthcare provider, and just 1 in 20 receive treatment from a mental health specialist.42 Latinx youth are half as likely as white youth to receive antidepressant or stimulant treatment for depression and anxiety or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and attention deficit disorder (ADD), respectively.43 In addition to fears of deportation, experiences of discrimination and mistrust of the healthcare system contribute to patterns of healthcare avoidance and non-adherence to recommended treatments.44

Many of the barriers to mental health care are rooted in the same factors that drive disparities in negative health conditions. For instance, immigration policies are often designed to explicitly and systematically exclude immigrant communities, especially undocumented individuals. Further, even when immigrants do access services, they face discrimination that can further activate mental health trauma. The provision of services in English only also creates major barriers for communities that speak Spanish or any number of non-English and Indigenous languages. Beyond that, Latinx migrant communities are often economically exploited and therefore face barriers at disparately high rates, including the cost of services themselves, access to childcare, transportation, and the inability to take time off from work. While these barriers are well-documented, more attention is needed to connect these disparities with potential solutions that can close equity gaps. In the face of nearly insurmountable odds, many Latinxs cultivate positive mental health and access services as needed.

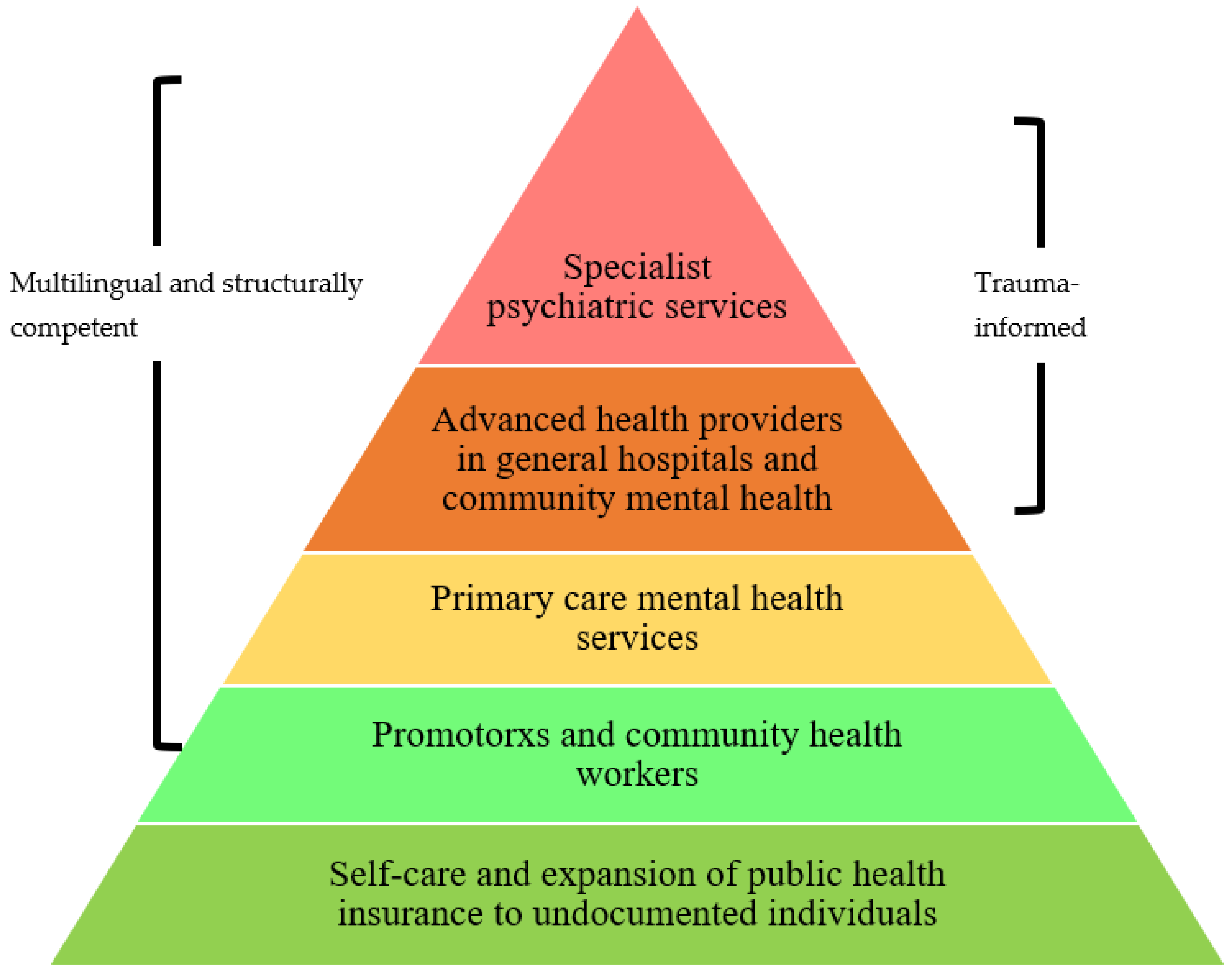

Mario Alberto Viveros Espinoza-Kulick and Jessica Cerdeña proposed a comprehensive model for mental health services for Latinx (im)migrant communities, modified from the World Health Organization Optimal Mix of Services Pyramid, which is shown in Figure 9.2.2. From bottom to top, the base layer is green and labeled, “Self-care and expansion of public health insurance to undocumented individuals.” The second layer is a lighter green and labelled, “Promotorxs and community health workers.” The third layer is yellow and labelled, “Primary care mental health services.” The fourth layer is labelled, “Advanced health providers in general hospitals and community mental health.” The top layer is labelled, “Specialist psychiatric services.” The second through fifth layers are labelled, “Multilingual and structurally competent.” The fourth and fifth layers are also labelled “Trauma-informed.”

migrant_Communities.png?revision=2&size=bestfit&width=600&height=474)

Figure 9.2.2: “Mental Health Services Pyramid for Latinx (Im)migrant Communities” by Mario Alberto V. Espinoza-Kulick and Jessica P. Cerdeña, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health is licensed CC BY 4.0.

This model provides a starting point for providers and evaluators to identify the gaps and next steps in solving the inequities in mental healthcare for Chicanxs and Latinxs. Fundamental to addressing the mental health needs of the widest group of individuals is to expand public health insurance programs, including undocumented individuals of all ages. Further, additional funding and resources are needed to increase access points for service delivery, which often begins with community health workers. Starting from this point, it is vital to ensure accessibility by providing multilingual interpretation services for individuals seeking care. Increasing capacity for these preventative measures can reduce the strain on general and specialty care providers and provide more effective care for all. However, even for those who do need more intensive forms of mental health care, communities would benefit from more providers who are structurally competent, meaning that they can assess how environmental and social factors may be influencing the individual health of their patients. Related, at every level of care, paid interpreters can ensure multilingual services. Lastly, effective advanced health providers and specialty psychiatric services benefit from utilizing a trauma-informed approach, to identify and address the potentially traumatic events influencing individuals’ high mental health burden.

Sidebar: LGBTQ2S+ Chicanx and Latinx Youth Mental Health

Mental health issues within Chicanx and Latinx communities can be especially challenging for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, Two-Spirit, and similarly identified young people.45 Chicanx and Latinx LGBTQ2S+ youth may experience additional distress due to homophobia and transphobia, as well as heterosexism and cissexism. Part of the reason is the stress-related stigma, discrimination, and difficulties expressing gender and sexual identity, which many LGBTQ2S+ people of color face. (See Chapter 6 for more on this topic). In addition, Chicanx and Latinx youth may face particular barriers related to their immigration status, family, and language accessibility. Coming out as LGBTQ2S+ may increase an individual’s risk of family rejection. Cultural messages in society in general and among Chicanx and Latinx communities about LGBTQ2S+ people communicate denigration and stigma. Further, existing resources and supportive communities for LGBTQ2S+ people tend to exclude Latinxs, oftentimes are not accessible in Spanish, and tend to take an individual approach that does not address the root causes of family rejection or social exclusion.

Footnotes

15 Flores, Chicana and Chicano Mental Health.

16 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Hispanics, Latino or Spanish Origin or Descent,” Annual Report (Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Association, January 14, 2020).

17 Margarita Alegria, Glorisa Canino, Patrick E. Shrout, Meghan Woo, Naihua Duan, Doryliz Vila, Maria Torres, Chih-nan Chen, and Xiao-Li Meng. “Prevalence of Mental Illness in Immigrant and Non-Immigrant U.S. Latino Groups,” The American Journal of Psychiatry 165, no. 3 (March 2008): 359–69, https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07040704.

18 Content in this section is drawn from Mario Alberto V. Espinoza-Kulick and Jessica P. Cerdeña, “We Need Health for All”: Mental Health and Barriers to Care among Latinxs in California and Connecticut.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 19 (2022): 12817; https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912817 which is licensed CC BY 4.0.

19 Maria Jose Lisotto, “Mental Health Disparities: Hispanics and Latinos” (American Psychiatric Association, 2017); Laura Kann, Tim McManus, William A. Harris, Shari L. Shanklin, Katherine H. Flint, Barbara Queen, Richard Lowry, David Chyen, Lisa Whittle, Jemekia Thornton, Connie Lim, Denise Bradford, Yoshimi Yamakawa, Michelle Leon, Nancy Brener, and Kathleen A. Ethier. “Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2017,” Surveillance Summaries, Surveillance Summaries, 67, no. 8 (June 15, 2018): 1–114, http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1.

20 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “Behavioral Health Barometer: United States, 2015” (Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015).

21 Tracy Chu, Allen S. Keller, and Andrew Rasmussen, “Effects of Post-Migration Factors on PTSD Outcomes among Immigrant Survivors of Political Violence,” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 15, no. 5 (2013): 890–97; Krista M. Perreira and India Ornelas, “Painful Passages: Traumatic Experiences and Post-Traumatic Stress among US Immigrant Latino Adolescents and Their Primary Caregivers,” International Migration Review 47, no. 4 (2013): 976–1005; Wendy A. Vogt, “Crossing Mexico: Structural Violence and the Commodification of Undocumented Central American Migrants,” American Ethnologist 40, no. 4 (2013): 764–80; Wendy A. Vogt, Lives in Transit: Violence and Intimacy on the Migrant Journey, vol. 42 (California Series in Public An, 2018).

22 Elizabeth Miller, Michele R. Decker, Jay G. Silverman, and Anita Raj, “Migration, Sexual Exploitation, and Women’s Health: A Case Report from a Community Health Center,” Violence Against Women 13, no. 5 (2007): 486–97; Charlotte Watts and Cathy Zimmerman, “Violence against Women: Global Scope and Magnitude,” The Lancet 359, no. 9313 (2002): 1232–37.

23 Carol Cleaveland and Cara Frankenfeld, “‘They Kill People Over Nothing’: An Exploratory Study of Latina Immigrant Trauma,” Journal of Social Service Research 46, no. 4 (August 2020): 507–23, https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2019.1602100; Lisa R. Fortuna, Kiara Álvarez, Zorangeli Ramos Ortiz, Ye Wang, Xulian Mozo Algería, Benjamin Cook, and Margarita Algería, “Mental Health, Migration Stressors and Suicidal Ideation among Latino Immigrants in Spain and the United States,” European Psychiatry 36 (August 2016): 15–22, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.03.001; Stacey Kaltman, Alejandra Hurtado de Mendoza, Adriana Serrano, Felisa A. Gonzales, “A Mental Health Intervention Strategy for Low-Income, Trauma-Exposed Latina Immigrants in Primary Care: A Preliminary Study,” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 86, no. 3 (2016): 345–54, https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000157.

24 Jessica P Cerdeña, Luisa M Rivera, and Judy M Spak, “Intergenerational Trauma in Latinxs: A Scoping Review” (Unpublished manuscript, 2020).

25 Rachel Treisman, “Whistleblower Alleges ‘Medical Neglect,’ Questionable Hysterectomies Of ICE Detainees,” NPR, September 16, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/09/16/913398383/whistleblower-alleges-medical-neglect-questionable-hysterectomies-of-ice-detaine.

26 Annahir N. Cariello, Paul B. Perrin, Chelsea Derlan Williams, Antonio G. Espinoza, Alejandra Morlett-Paredes, Oswaldo Moreno, and Michal A. Trujillo. “Moderating Influence of Enculturation on the Relations between Minority Stressors and Physical Health via Anxiety in Latinx Immigrants,” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 26, no. 3 (July 2020): 356–66, https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000308.

27 Arthur R. Andrews III, James K. Haws, Laura M. Acosta, M. Natalia Acosta Canchilla, Gustavo Carlo, Kathleen M. Grant, and Athena K. Ramos. “Combinatorial Effects of Discrimination, Legal Status Fears, Adverse Childhood Experiences, and Harsh Working Conditions among Latino Migrant Farmworkers: Testing Learned Helplessness Hypotheses,” Journal of Latinx Psychology 8, no. 3 (August 2020): 179–201, https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000141.

28 Julia Shu-Huah Wang and Neeraj Kaushal, “Health and Mental Health Effects of Local Immigration Enforcement,” International Migration Review 53, no. 4 (2019): 970–1001.

29 Omar Martinez, Elwin Wu, Theo Sandfort, Brian Dodge, Alex Carballo-Dieguez, Rogerio Pinto, Scott D. Rhodes, Eva Moya, and Silvia Chavez-Baray. “Evaluating the Impact of Immigration Policies on Health Status Among Undocumented Immigrants: A Systematic Review,” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health / Center for Minority Public Health 17, no. 3 (June 2015): 947–70, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-013-9968-4.

30 Edward D. Vargas, Gabriel R. Sanchez, and Melina Juárez, “Fear by Association: Perceptions of Anti-Immigrant Policy and Health Outcomes,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 42, no. 3 (June 2017): 459–83, https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-3802940.

31 Sandraluz Lara-Cinisomo, Elinor M. Fujimoto, Christine Oksas, Yafei Jian, and Allen Gharheeb, “Pilot Study Exploring Migration Experiences and Perinatal Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Immigrant Latinas,” Maternal and Child Health Journal 23, no. 12 (December 2019): 1627–47, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-019-02800-w.

32 Scott D. Rhodes, Lilli Mann, Florence M. Simán, Eunyoung Song, Jorge Alonzo, Mario Downs, Emma Lawlor, Omar Martinez, Christina J. Sun, Mary Claire O’Brien. “The Impact of Local Immigration Enforcement Policies on the Health of Immigrant Hispanics/Latinos in the United States,” American Journal of Public Health 105, no. 2 (2015): 329–37.

33 Emilie Bruzelius and Aaron Baum, “The Mental Health of Hispanic/Latino Americans Following National Immigration Policy Changes: United States, 2014–2018,” American Journal of Public Health 109, no. 12 (December 2019): 1786–88, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305337.

34 Karen Hacker, Jocelyn Chu, Carolyn Leung, Robert Marra, Alex Pirie, Mohamed Brahimi, Margaret English, Joshua Beckmann, Dolores Avecedo-Garcia, and Robert P. Marlin. “The Impact of Immigration and Customs Enforcement on Immigrant Health: Perceptions of Immigrants in Everett, Massachusetts, USA,” Social Science and Medicine 73, no. 4 (August 1, 2011): 586–94, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.007; William D. Lopez, Daniel J. Kruger, Jorge Delva, Mikel Llanes, Charo Ledón, Adreanne Waller, Melanie Harner, Ramiro Martinez, Laura Sanders, Margaret Harner, and Barbara Israel, “Health Implications of an Immigration Raid: Findings from a Latino Community in the Midwestern United States,” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 19, no. 3 (June 2017): 702–8, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-016-0390-6.

35 American Immigration Council, “Summary of Executive Order ‘Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States,’” American Immigration Council, May 19, 2017, https://www.americanimmigrationcounc...xecutive-order; Lucila Ramos-Sánchez, Kipp Pietrantonio, and Jasmín Llamas, “The Psychological Impact of Immigration Status on Undocumented Latinx Women: Recommendations for Mental Health Providers,” Peace and Conflict 26, no. 2 (May 2020): 149–61, https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000417.

36 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, “Temporary Protected Status Designated Country: Nicaragua,” November 1, 2019, https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/temporary-protected-status/temporary-protected-status-designated-country-nicaragua.

37 Philippe Bourgois, Seth M. Holmes, Kim Sue, and James Quesada, “Structural Vulnerability: Operationalizing the Concept to Address Health Disparities in Clinical Care,” Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges 92, no. 3 (2017): 299.

38 Andrews et al. “Combinatorial Effects of Discrimination, Legal Status Fears, Adverse Childhood Experiences, and Harsh Working Conditions among Latino Migrant Farmworkers.”

39 Erin Quinn and Sally Kinoshita, “An Overview of Public Charge and Benefits” (San Francisco, CA: Immigrant Legal Resource Center, March 26, 2020).

40 Samantha Artiga and Maria Diaz, “Health Coverage and Care of Undocumented Immigrants,” Kaiser Family Foundation (blog), July 2019, http://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-Health-Coverage-and-Care-of-Undocumented-Immigrants; Linda Bucay-Harari, Kathleen R. Page, Noa Krawczyk, Yvonne P. Robles, Carlos Castillo-Salgado, “Mental Health Needs of an Emerging Latino Community,” Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 47, no. 3 (July 2020): 388–98, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-020-09688-3.

41 Robin A Cohen et al., “Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates From the National Health Interview Survey, 2019” (Atlanta, GA: National Center for Health Statistics, September 2020).

42 Office of the Surgeon General (US), Center for Mental Health Services (US), and National Institute of Mental Health (US), Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General, Publications and Reports of the Surgeon General (Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US), 2001), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44243/.

43 Julie L. Hudson, G. Edward Miller, and James B. Kirby, “Explaining Racial and Ethnic Differences in Children’s Use of Stimulant Medications,” Medical Care 45, no. 11 (2007): 1068–75; James B. Kirby, Julie Hudson, and G. Edward Miller, “Explaining Racial and Ethnic Differences in Antidepressant Use Among Adolescents,” Medical Care Research and Review 67, no. 3 (June 1, 2010): 342–63, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558709350884.

44 Frank H. Galvan, Laura M. Bogart, David J. Klein, Glenn J. Wagner, and Ying-Tung Chen, “Medical Mistrust as a Key Mediator in the Association between Perceived Discrimination and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy among HIV-Positive Latino Men,” Journal of Behavioral Medicine 40, no. 5 (October 1, 2017): 784–93, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-017-9843-1.

45 Javier Garcia-Perez, “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer+ Latinx Youth Mental Health Disparities: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services 32, no. 4 (2020):440–478; Flores, Chicana and Chicano Mental Health.