17.2: Defining Foreign Policy

- Page ID

- 153758

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain what foreign policy is and how it differs from domestic policy

- Identify the objectives of U.S. foreign policy

- Describe the different types of foreign policy

- Identify the U.S. government’s main challenges in the foreign policy realm

When we consider policy as our chapter focus, we are looking broadly at the actions the U.S. government carries out for particular purposes. In the case of foreign policy, that purpose is to manage its relationships with other nations of the world. Another distinction is that policy results from a course of action or a pattern of actions over time, rather than from a single action or decision. For example, U.S. foreign policy with Russia has been forged by several presidents, as well as by cabinet secretaries, House and Senate members, and foreign policy agency bureaucrats. Policy is also purposive, or intended to do something; that is, policymaking is not random. When the United States enters into an international agreement with other countries on aims such as free trade or nuclear disarmament, it does so for specific reasons. With that general definition of policy established, we shall now dig deeper into the specific domain of U.S. foreign policy.

Foreign Policy Basics

What is foreign policy? We can think of it on several levels, as “the goals that a state’s officials seek to attain abroad, the values that give rise to those objectives, and the means or instruments used to pursue them.”1 This definition highlights some of the key topics in U.S. foreign policy, such as national goals abroad and the manner in which the United States tries to achieve them. Note too that we distinguish foreign policy, which is externally focused, from domestic policy, which sets strategies internal to the United States, though the two types of policies can become quite intertwined. So, for example, one might talk about Latino politics as a domestic issue when considering educational policies designed to increase the number of Hispanic Americans who attend and graduate from a U.S. college or university.2 However, as demonstrated in the primary debates leading up to the 2016 election, Latino politics can quickly become a foreign policy matter when considering topics such as immigration from and foreign trade with countries in Central America and South America (Figure 17.2).3

What are the objectives of U.S. foreign policy? While the goals of a nation’s foreign policy are always open to debate and revision, there are nonetheless four main goals to which we can attribute much of what the U.S. government does in the foreign policy realm: (1) the protection of the U.S. and its citizens, (2) the maintenance of access to key resources and markets, (3) the preservation of a balance of power in the world, and (4) the protection of human rights and democracy.

The first goal is the protection of the United States and the lives of it citizens, both while they are in the United States and when they travel abroad. Related to this security goal is the aim of protecting the country’s allies, or countries with which the United States is friendly and mutually supportive. In the international sphere, threats and dangers can take several forms, including military threats from other nations or terrorist groups and economic threats from boycotts and high tariffs on trade. An economic sanction occurs when a country or multiple countries suspend trade or other financial relationships with another country in order to signal their displeasure with the behavior of the other country.

In an economic boycott, the United States ceases trade with another country unless or until it changes a policy to which the United States objects. Ceasing trade means U.S. goods cannot be sold in that country and its goods cannot be sold in the United States. For example, in recent years the United States and other countries implemented an economic boycott of Iran as it escalated the development of its nuclear energy program. The recent Iran nuclear deal is a pact in which Iran agrees to halt nuclear development while the United States and six other countries lift economic sanctions to again allow trade with Iran. Barriers to trade also include tariffs, or fees charged for moving goods from one country to another. Protectionist trade policies raise tariffs so that it becomes difficult for imported goods, now more expensive, to compete on price with domestic goods. Free trade agreements seek to reduce these trade barriers.

The second main goal of U.S. foreign policy is to ensure the nation maintains access to key resources and markets across the world. Resources include natural resources, such as oil, and economic resources, including the infusion of foreign capital investment for U.S. domestic infrastructure projects like buildings, bridges, and weapons systems. Of course, access to the international marketplace also means access to goods that American consumers might want, such as Swiss chocolate and Australian wine. U.S. foreign policy also seeks to advance the interests of U.S. business, to both sell domestic products in the international marketplace and support general economic development around the globe (especially in developing countries).

A third main goal is the preservation of a balance of power in the world. A balance of power means no one nation or region is much more powerful militarily than are the countries of the rest of the world. The achievement of a perfect balance of power is probably not possible, but general stability, or predictability in the operation of governments, strong institutions, and the absence of violence within and between nations may be. For much of U.S. history, leaders viewed world stability through the lens of Europe. If the European continent was stable, so too was the world. During the Cold War era that followed World War II, stability was achieved by the existence of dual superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, and by the real fear of the nuclear annihilation of which both were capable. Until approximately 1989–1990, advanced industrial democracies aligned themselves behind one of these two superpowers.

Today, in the post–Cold War era, many parts of Europe are politically more free than they were during the years of the Soviet bloc, and there is less fear of nuclear war than when the United States and the Soviet Union had missiles pointed at each other for four straight decades. However, despite the mostly stabilizing presence of the European Union (EU), which now has twenty-eight member countries, several wars have been fought in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Moreover, the EU itself faces some challenges, including a vote in the United Kingdom to leave the EU, the ongoing controversy about how to resolve the national debt of Greece, and the crisis in Europe created by thousands of refugees from the Middle East.

Carefully planned acts of terrorism in the United States, Asia, and Europe have introduced a new type of enemy into the balance of power equation—nonstate or nongovernmental organizations, such as al-Qaeda and ISIS (or ISIL), consisting of various terrorist cells located in many different countries and across all continents (Figure 17.3).

The fourth main goal of U.S. foreign policy is the protection of human rights and democracy. The payoff of stability that comes from other U.S. foreign policy goals is peace and tranquility. While certainly looking out for its own strategic interests in considering foreign policy strategy, the United States nonetheless attempts to support international peace through many aspects of its foreign policy, such as foreign aid, and through its support of and participation in international organizations such as the United Nations, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and the Organization of American States.

The United Nations (UN) is perhaps the foremost international organization in the world today. The main institutional bodies of the UN are the General Assembly and the Security Council. The General Assembly includes all member nations and admits new members and approves the UN budget by a two-thirds majority. The Security Council includes fifteen countries, five of which are permanent members (including the United States) and ten that are nonpermanent and rotate on a five-year-term basis. The entire membership is bound by decisions of the Security Council, which makes all decisions related to international peace and security. Two other important units of the UN are the International Court of Justice in The Hague (Netherlands) and the UN Secretariat, which includes the Secretary-General of the UN and the UN staff directors and employees.

The Creation of the United Nations

One of the unique and challenging aspects of global affairs is the fact that no world-level authority exists to mandate when and how the world’s nations interact. After the failed attempt by President Woodrow Wilson and others to formalize a “League of Nations” in the wake of World War I in the 1920s, and on the heels of a worldwide depression that began in 1929, came World War II, history’s deadliest military conflict. Now, in the early decades of the twenty-first century, it is common to think of the September 11 terrorist attacks in 2001 as the big game-changer. Yet while 9/11 was hugely significant in the United States and abroad, World War II was even more so. The December 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor (Hawaii) was a comparable surprise-style attack that plunged the United States into war.

The scope of the conflict, fought in Europe and the Pacific Ocean, and Hitler’s nearly successful attempt to take over Europe entirely, struck fear in minds and hearts. The war brought about a sea change in international relations and governance, from the Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe, to NATO that created a cross-national military shield for Western Europe, to the creation of the UN in 1945, when the representatives of fifty countries met and signed the Charter of the United Nations in San Francisco, California (Figure 17.4).

Today, the United Nations, headquartered in New York City, includes 193 of the 195 nations of the world. It is a voluntary association to which member nations pay dues based on the size of their economy. The UN’s main purposes are to maintain peace and security, promote human rights and social progress, and develop friendly relationships among nations.

Follow-up activity: In addition to facilitating collective decision-making on world matters, the UN carries out many different programs. Go to the UN website to find information about three different UN programs that are carried out around the world.

An ongoing question for the United States in waging the war against terrorism is to what degree it should work in concert with the UN to carry out anti-terrorism initiatives around the world in a multilateral manner, rather than pursuing a “go it alone” strategy of unilateralism. The fact that the U.S. government has such a choice suggests the voluntary nature of the United States (or another country) accepting world-level governance in foreign policy. If the United States truly felt bound by UN opinion regarding the manner in which it carries out its war on terrorism, it would approach the UN Security Council for approval.

Another cross-national organization to which the United States is tied, and that exists to forcefully represent Western allies and in turn forge the peace, is the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). NATO was formed after World War II as the Cold War between East and West started to emerge. While more militaristic in approach than the United Nations, NATO has the goal of protecting the interests of Europe and the West and the assurance of support and defense from partner nations. However, while it is a strong military coalition, it has not sought to expand and take over other countries. Rather, the peace and stability of Europe are its main goals. NATO initially included only Western European nations and the United States. However, since the end of the Cold War, additional countries from the East, such as Turkey, have entered into the NATO alliance.

Besides participating in the UN and NATO, the United States also distributes hundreds of billions of dollars each year in foreign aid to improve the quality of life of citizens in developing countries. The United States may also forgive the foreign debts of these countries. By definition, developing countries are not modernized in terms of infrastructure and social services and thus suffer from instability. Helping them modernize and develop stable governments is intended as a benefit to them and a prop to the stability of the world. An alternative view of U.S. assistance is that there are more nefarious goals at work, that perhaps it is intended to buy influence in developing countries, secure a position in the region, obtain access to resources, or foster dependence on the United States.

The United States pursues its four main foreign policy goals through several different foreign policy types, or distinct substantive areas of foreign policy in which the United States is engaged. These types are trade, diplomacy, sanctions, military/defense, intelligence, foreign aid, and global environmental policy.

Trade policy is the way the United States interacts with other countries to ease the flow of commerce and goods and services between countries. A country is said to be engaging in protectionism when it does not permit other countries to sell goods and services within its borders, or when it charges them very high tariffs (or import taxes) to do so. At the other end of the spectrum is a free trade approach, in which a country allows the unfettered flow of goods and services between itself and other countries. At times the United States has been free trade–oriented, while at other times it has been protectionist. Perhaps its most free trade–oriented move was the 1991 implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). This pact removed trade barriers and other transaction costs levied on goods moving between the United States, Mexico, and Canada.

Critics see a free trade approach as problematic and instead advocate for protectionist policies that shield U.S. companies and their products against cheaper foreign products that might be imported here. One of the more prominent recent examples of protectionist policies occurred in the steel industry, as U.S. companies in the international steel marketplace struggled with competition from Chinese factories in particular.

The balance of trade is the relationship between a country’s inflow and outflow of goods. The United States sells many goods and services around the world, but overall it maintains a trade deficit, in which more goods and services are coming in from other countries than are going out to be sold overseas. The current U.S. trade deficit is $37.4 billion, which means the value of what the United States imports from other countries is much larger than the value of what it exports to other countries.4 This trade deficit has led some to advocate for protectionist trade policies.

For many, foreign policy is synonymous with diplomacy. Diplomacy is the establishment and maintenance of a formal relationship between countries that governs their interactions on matters as diverse as tourism, the taxation of goods they trade, and the landing of planes on each other’s runways. While diplomatic relations are not always rosy, when they are operating it does suggest that things are going well between the countries. Diplomatic relations are formalized through the sharing of ambassadors. Ambassadors are country representatives who live and maintain an office (known as an embassy) in the other country. Just as exchanging ambassadors formalizes the bilateral relationship between countries, calling them home signifies the end of the relationship. Diplomacy tends to be the U.S. government’s first step when it tries to resolve a conflict with another country.

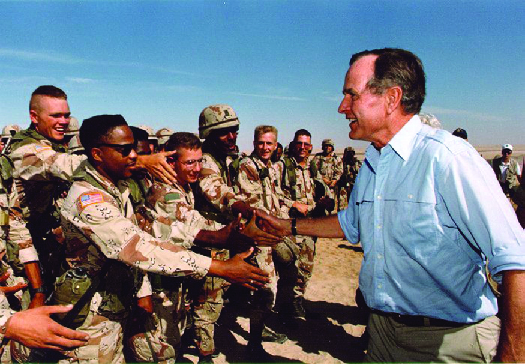

At the more serious end of the foreign policy decision-making spectrum, and usually as a last resort when diplomacy fails, the U.S. military and defense establishment exists to provide the United States the ability to wage war against other state and nonstate actors. Such war can be offensive, as were the Iraq War in 2003 and the 1989 removal of Panamanian leader Manuel Noriega. Or it can be defensive, as a means to respond to aggression from others, such as the Persian Gulf War in 1991, also known as Operation Desert Storm (Figure 17.5). The potential for military engagement, and indeed the scattering about the globe of hundreds of U.S. military installations, can also be a potential source of foreign policy strength for the United States. On the other hand, in the world of diplomacy, such an approach can be seen as imperialistic by other world nations.

Intelligence policy is related to defense and includes the overt and covert gathering of information from foreign sources that might be of strategic interest to the United States. The intelligence world, perhaps more than any other area of foreign policy, captures the imagination of the general public. Many books, television shows, and movies entertain us (with varying degrees of accuracy) through stories about U.S. intelligence operations and people.

Global environmental policy addresses world-level environmental matters such as climate change and global warming, the thinning of the ozone layer, rainforest depletion in areas along the Equator, and ocean pollution and species extinction. The United States’ commitment to such issues has varied considerably over the years. For example, the United States was the largest country not to sign the 1997 Kyoto Protocol on greenhouse gas emissions. However, few would argue that the U.S. government has not been a leader on global environmental matters. The Paris Agreement on climate change took effect in late 2016. The pact establishes a framework to prevent further climate change, namely to limit the rise in overall global temperature. The agreement was negotiated during the Obama administration and the U.S. signed on initially. However, President Trump officially withdrew the U.S. from the pact in November 2020. Early in 2021, the newly elected president, Joe Biden, rejoined the Paris Agreement with a commitment to cut greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2030.7

Unique Challenges in Foreign Policy

U.S. foreign policy is a massive and complex enterprise. What are its unique challenges for the country?

First, there exists no true world-level authority dictating how the nations of the world should relate to one another. If one nation negotiates in bad faith or lies to another, there is no central world-level government authority to sanction that country. This makes diplomacy and international coordination an ongoing bargain as issues evolve and governmental leaders and nations change. Foreign relations are certainly made smoother by the existence of cross-national voluntary associations like the United Nations, the Organization of American States, and the African Union. However, these associations do not have strict enforcement authority over specific nations, unless a group of member nations takes action in some manner (which is ultimately voluntary).

The European Union is the single supranational entity with some real and significant authority over its member nations. Adoption of its common currency, the euro, brings with it concessions from countries on a variety of matters, and the EU’s economic and environmental regulations are the strictest in the world. Yet even the EU has enforcement issues, as evidenced by the battle within its ranks to force member Greece to reduce its national debt or the recurring problem of Spain overfishing in the North Atlantic Ocean. The withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union (commonly referred to as Brexit, short for British exit) also points to the struggles that supra-national institutions like the EU can face.

International relations take place in a relatively open venue in which it is seldom clear how to achieve collective action among countries generally or between the United States and specific other nations in particular. When does it make sense to sign a multinational pact and when doesn’t it? Is a particular bilateral economic agreement truly as beneficial to the United States as to the other party, or are we giving away too much in the deal? These are open and complicated questions, which the various schools of thought discussed later in the chapter will help us answer.

A second challenge for the United States is the widely differing views among countries about the role of government in people’s lives. The government of hardline communist North Korea regulates everything in its people’s lives every day. At the other end of the spectrum are countries with little government activity at all, such as parts of the island of New Guinea. In between is a vast array of diverse approaches to governance. Countries like Sweden provide cradle-to-grave human services programs like health care and education that in some parts of India are minimal at best. In Egypt, the nonprofit sector provides many services rather than the government. The United States relishes its tradition of freedom and the principle of limited government, but practice and reality can be somewhat different. In the end, it falls somewhere in the middle of this continuum because of its focus on law and order, educational and training services, and old-age pensions and health care in the form of Social Security and Medicare.

The challenge of pinpointing the appropriate role of government may sound more like a domestic than a foreign policy matter, and to some degree it is an internal choice about the way government interacts with the people. Yet the internal (or domestic) relationship between a government and its people can often become intertwined with foreign policy. For example, the narrow stance on personal liberty that Iran has taken in recent decades led other countries to impose economic sanctions that crippled the country internally. Some of these sanctions have eased in light of the new nuclear deal with Iran. So the domestic and foreign policy realms are intertwined in terms of what we view as national priorities—whether they consist of nation building abroad or infrastructure building here at home, for example. This latter choice is often described as the “guns versus butter” debate.

A third, and related, unique challenge for the United States in the foreign policy realm is other countries’ varying ideas about the appropriate form of government. These forms range from democracies on one side to various authoritarian (or nondemocratic) forms of government on the other. Relations between the United States and democratic states tend to operate more smoothly, proceeding from the shared core assumption that government’s authority comes from the people. Monarchies and other nondemocratic forms of government do not share this assumption, which can complicate foreign policy discussions immensely. People in the United States often assume that people who live in a nondemocratic country would prefer to live in a democratic one. However, in some regions of the world, such as the Middle East, this does not seem to be the case—people often prefer having stability within a nondemocratic system over changing to a less predictable democratic form of government. Or they may believe in a theocratic form of government. And the United States does have formal relations with some more totalitarian and monarchical governments, such as Saudi Arabia, when it is in U.S. interests to do so.

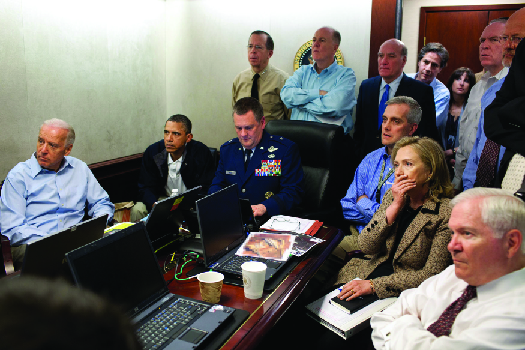

A fourth challenge is that many new foreign policy issues transcend borders. That is, there are no longer simply friendly states and enemy states. Problems around the world that might affect the United States, such as terrorism, the international slave trade, and climate change, originate with groups and issues that are not country-specific. They are transnational. So, for example, while we can readily name the enemies of the Allied forces in World War II (Germany, Italy, and Japan), the U.S. war against terrorism has been aimed at terrorist groups that do not fit neatly within the borders of any one country with which the United States could quickly interact to solve the problem. Intelligence-gathering and focused military intervention are needed more than traditional diplomatic relations, and relations can become complicated when the United States wants to pursue terrorists within other countries’ borders. An ongoing example is the use of U.S. drone strikes on terrorist targets within the nation of Pakistan, in addition to the 2011 campaign that resulted in the death of Osama bin Laden, the founder of al-Qaeda (Figure 17.6).

The fifth and final unique challenge is the varying conditions of the countries in the world and their effect on what is possible in terms of foreign policy and diplomatic relations. Relations between the United States and a stable industrial democracy are going to be easier than between the United States and an unstable developing country being run by a military junta (a group that has taken control of the government by force). Moreover, an unstable country will be more focused on establishing internal stability than on broader world concerns like environmental policy. In fact, developing countries are temporarily exempt from the requirements of certain treaties while they seek to develop stable industrial and governmental frameworks.

The Council on Foreign Relations is one of the nation’s oldest organizations that exist to promote thoughtful discussion on U.S. foreign policy.