3.1: Human Genetics

- Page ID

- 76875

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Psychological researchers study genetics in order to better understand the biological factors that contribute to certain behaviors. While all humans share certain biological mechanisms, we are each unique. And while our bodies have many of the same parts—brains and hormones and cells with genetic codes—these are expressed in a wide variety of behaviors, thoughts, and reactions.

Why do two people infected by the same disease have different outcomes: one surviving and one succumbing to the ailment? How are genetic diseases passed through family lines? Are there genetic components to psychological disorders, such as depression or schizophrenia? To what extent might there be a psychological basis to health conditions such as childhood obesity?

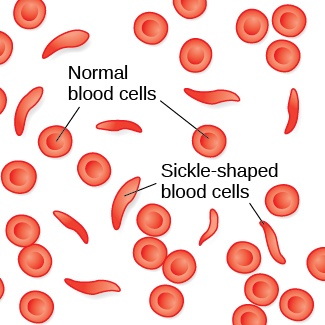

To explore these questions, let’s start by focusing on a specific genetic disorder, sickle cell anemia, and how it might manifest in two affected sisters. Sickle-cell anemia is a genetic condition in which red blood cells, which are normally round, take on a crescent-like shape (Figure 3.2). The changed shape of these cells affects how they function: sickle-shaped cells can clog blood vessels and block blood flow, leading to high fever, severe pain, swelling, and tissue damage.

Many people with sickle-cell anemia—and the particular genetic mutation that causes it—die at an early age. While the notion of “survival of the fittest” may suggest that people suffering from this disorder have a low survival rate and therefore the disorder will become less common, this is not the case. Despite the negative evolutionary effects associated with this genetic mutation, the sickle-cell gene remains relatively common among people of African descent. Why is this? The explanation is illustrated with the following scenario.

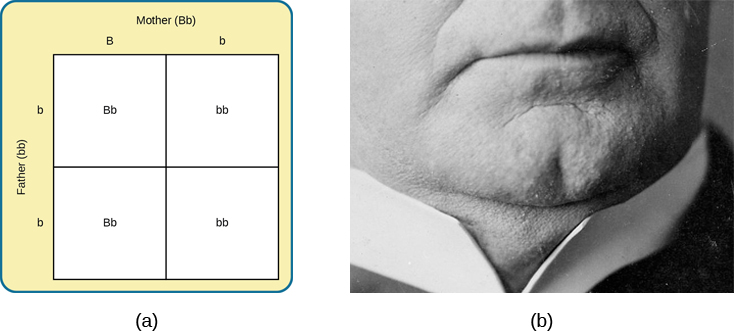

Imagine two young women—Luwi and Sena—sisters in rural Zambia, Africa. Luwi carries the gene for sickle-cell anemia; Sena does not carry the gene. Sickle-cell carriers have one copy of the sickle-cell gene but do not have full-blown sickle-cell anemia. They experience symptoms only if they are severely dehydrated or are deprived of oxygen (as in mountain climbing). Carriers are thought to be immune from malaria (an often deadly disease that is widespread in tropical climates) because changes in their blood chemistry and immune functioning prevent the malaria parasite from having its effects (Gong, Parikh, Rosenthal, & Greenhouse, 2013). However, full-blown sickle-cell anemia, with two copies of the sickle-cell gene, does not provide immunity to malaria.

While walking home from school, both sisters are bitten by mosquitos carrying the malaria parasite. Luwi is protected against malaria because she carries the sickle-cell mutation. Sena, on the other hand, develops malaria and dies just two weeks later. Luwi survives and eventually has children, to whom she may pass on the sickle-cell mutation.

Malaria is rare in the United States, so the sickle-cell gene benefits nobody: the gene manifests primarily in minor health problems for carriers with one copy, or a severe full-blown disease with no health benefits for carriers with two copies. However, the situation is quite different in other parts of the world. In parts of Africa where malaria is prevalent, having the sickle-cell mutation does provide health benefits for carriers (protection from malaria).

The story of malaria fits with Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection (Figure 3.3). In simple terms, the theory states that organisms that are better suited for their environment will survive and reproduce, while those that are poorly suited for their environment will die off. In our example, we can see that, as a carrier, Luwi’s mutation is highly adaptive in her African homeland; however, if she resided in the United States (where malaria is rare), her mutation could prove costly—with a high probability of the disease in her descendants and minor health problems of her own.

It’s easy to get confused about two fields that study the interaction of genes and the environment, such as the fields of evolutionary psychology and behavioral genetics. How can we tell them apart?

In both fields, it is understood that genes not only code for particular traits, but also contribute to certain patterns of cognition and behavior. Evolutionary psychology focuses on how universal patterns of behavior and cognitive processes have evolved over time. Therefore, variations in cognition and behavior would make individuals more or less successful in reproducing and passing those genes on to their offspring. Evolutionary psychologists study a variety of psychological phenomena that may have evolved as adaptations, including fear response, food preferences, mate selection, and cooperative behaviors (Confer et al., 2010).

Whereas evolutionary psychologists focus on universal patterns that evolved over millions of years, behavioral geneticists study how individual differences arise, in the present, through the interaction of genes and the environment. When studying human behavior, behavioral geneticists often employ twin and adoption studies to research questions of interest. Twin studies compare the likelihood that a given behavioral trait is shared among identical and fraternal twins; adoption studies compare those rates among biologically related relatives and adopted relatives. Both approaches provide some insight into the relative importance of genes and environment for the expression of a given trait.

Genetic Variation

Gene-Environment Interactions

Summary

Glossary

- allele

- specific version of a gene

- chromosome

- long strand of genetic information

- deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA)

- helix-shaped molecule made of nucleotide base pairs

- dominant allele

- allele whose phenotype will be expressed in an individual that possesses that allele

- epigenetics

- study of gene-environment interactions, such as how the same genotype leads to different phenotypes

- fraternal twins

- twins who develop from two different eggs fertilized by different sperm, so their genetic material varies the same as in non-twin siblings

- gene

- sequence of DNA that controls or partially controls physical characteristics

- genetic environmental correlation

- view of gene-environment interaction that asserts our genes affect our environment, and our environment influences the expression of our genes

- genotype

- genetic makeup of an individual

- heterozygous

- consisting of two different alleles

- homozygous

- consisting of two identical alleles

- identical twins

- twins that develop from the same sperm and egg

- mutation

- sudden, permanent change in a gene

- phenotype

- individual’s inheritable physical characteristics

- polygenic

- multiple genes affecting a given trait

- range of reaction

- asserts our genes set the boundaries within which we can operate, and our environment interacts with the genes to determine where in that range we will fall

- recessive allele

- allele whose phenotype will be expressed only if an individual is homozygous for that allele

- theory of evolution by natural selection

- states that organisms that are better suited for their environments will survive and reproduce compared to those that are poorly suited for their environments