13.1: What Is Industrial and Organizational Psychology?

- Page ID

- 76960

In 2019, people who worked in the United States spent an average of about 42–54 hours per week working (Bureau of Labor Statistics—U.S. Department of Labor, 2019). Sleeping was the only other activity they spent more time on with an average of about 43–62 hours per week. The workday is a significant portion of workers’ time and energy. It impacts their lives and their family’s lives in positive and negative physical and psychological ways. Industrial and organizational (I-O) psychology is a branch of psychology that studies how human behavior and psychology affect work and how they are affected by work.

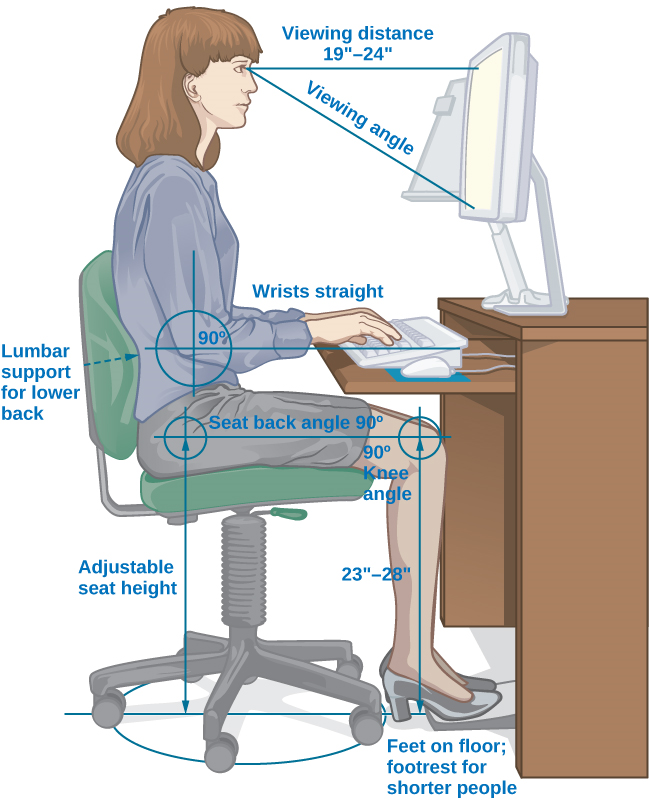

Industrial and organizational psychologists work in four main contexts: academia, government, consulting firms, and business. Most I-O psychologists have a master’s or doctorate degree. The field of I-O psychology can be divided into three broad areas (Figure 13.2 and Figure 13.3): industrial, organizational, and human factors. Industrial psychology is concerned with describing job requirements and assessing individuals for their ability to meet those requirements. In addition, once employees are hired, industrial psychology studies and develops ways to train, evaluate, and respond to those evaluations. As a consequence of its concern for candidate characteristics, industrial psychology must also consider issues of legality regarding discrimination in hiring. Organizational psychology is a discipline interested in how the relationships among employees affect those employees and the performance of a business. This includes studying worker satisfaction, motivation, and commitment. This field also studies management, leadership, and organizational culture, as well as how an organization’s structures, management and leadership styles, social norms, and role expectations affect individual behavior. As a result of its interest in worker wellbeing and relationships, organizational psychology also considers the subjects of harassment, including sexual harassment, and workplace violence. Human factors psychology is the study of how workers interact with the tools of work and how to design those tools to optimize workers’ productivity, safety, and health. These studies can involve interactions as straightforward as the fit of a desk, chair, and computer to a human having to sit on the chair at the desk using the computer for several hours each day. They can also include the examination of how humans interact with complex displays and their ability to interpret them accurately and quickly. In Europe, this field is referred to as ergonomics.

Occupational health psychology (OHP) deals with the stress, diseases, and disorders that can affect employees as a result of the workplace. As such, the field is informed by research from the medical, biological, psychological, organizational, human factors, human resources, and industrial fields. Individuals in this field seek to examine the ways in which the organization affects the quality of work life for an employee and the responses that employees have towards their organization or as a result of their organization’s influence on them. The responses for employees are not limited to the workplace as there may be some spillover into their personal lives outside of work, especially if there is not good work-life balance. The ultimate goal of an occupational health psychologist is to improve the overall health and well-being of an individual, and, as a result, increase the overall health of the organization (Society for Occupational Health Psychology, 2020).

In 2009, the field of humanitarian work psychology (HWP) was developed as the brainchild of a small group of I-O psychologists who met at a conference. Realizing they had a shared set of goals involving helping those who are underserved and underprivileged, the I-O psychologists formally formed the group in 2012 and have approximately 300 members worldwide. Although this is a small number, the group continues to expand. The group seeks to help marginalized members of society, such as people with low-income, find work. In addition, they help to determine ways to deliver humanitarian aid during major catastrophes. The Humanitarian Work Psychology group can also reach out to those in the local community who do not have the knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs) to be able to find gainful employment that would enable them to not need to receive aid. In both cases, humanitarian work psychologists try to help the underserved individuals develop KSAs that they can use to improve their lives and their current situations. When ensuring these underserved individuals receive training or education, the focus is on skills that, once learned, will never be forgotten and can serve individuals throughout their lifetimes as they seek employment (APA, 2016). Table 13.1 summarizes the main fields in I-O psychology, their focuses, and jobs within each field.

| Field of I-O Psychology | Description | Types of Jobs |

|---|---|---|

| Industrial Psychology | Specializes and focuses on the retention of employees and hiring practices to ensure the least number of firings and the greatest number of hirings relative to the organization’s size. |

Personnel Analyst Instructional Designer Professor Research Analyst |

| Organizational Psychology | Works with the relationships that employees develop with their organizations and conversely that their organization develops with them. In addition, studies the relationships that develop between co-workers and how that is influenced by organizational norms. |

HR Research Specialist Professor Project Consultant Personnel Psychologist Test Developer Training Developer Leadership Developer Talent Developer |

| Human Factors and Engineering | Researches advances and changes in technology in an effort to improve the way technology is used by consumers, whether with consumer products, technologies, transportation, work environments, or communications. Seeks to be better able to predict the ways in which people can and will utilize technology and products in an effort to provide improved safety and reliability. |

Professor Ergonomist Safety Scientist Project Consultant Inspector Research Scientist Marketer Product Development |

| Humanitarian Work Psychology | Works to improve the conditions of individuals who have faced serious disaster or who are part of an underserved population. Focuses on labor relations, enhancing public health services, effects on populations due to climate change, recession, and diseases. |

Professor Instructional Designer Research Scientist Counselor Consultant Program Manager Senior Response Officer |

| Occupational Health Psychology | Concerned with the overall well-being of both employees and organizations. |

Occupational Therapist Research Scientist Consultant Human Resources (HR) Specialist Professor |

The Historical Development of Industrial and Organizational Psychology

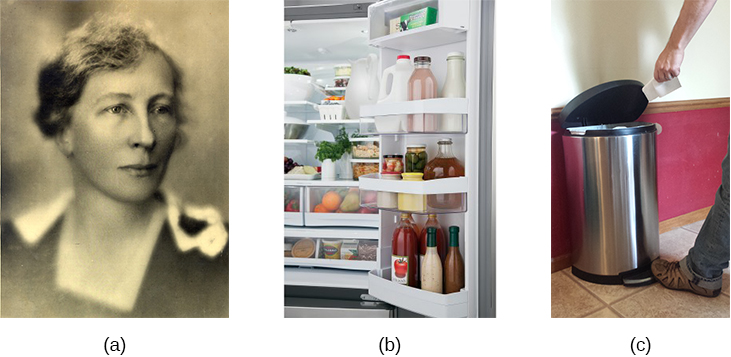

Industrial and organizational psychology had its origins in the early 20th century. Several influential early psychologists studied issues that today would be categorized as industrial psychology: James Cattell (1860–1944), Hugo Münsterberg (1863–1916), Walter Dill Scott (1869–1955), Robert Yerkes (1876–1956), Walter Bingham (1880–1952), and Lillian Gilbreth (1878–1972). Cattell, Münsterberg, and Scott had been students of Wilhelm Wundt, the father of experimental psychology. Some of these researchers had been involved in work in the area of industrial psychology before World War I. Cattell’s contribution to industrial psychology is largely reflected in his founding of a psychological consulting company, which is still operating today called the Psychological Corporation, and in the accomplishments of students at Columbia in the area of industrial psychology. In 1913, Münsterberg published Psychology and Industrial Efficiency, which covered topics such as employee selection, employee training, and effective advertising.

Scott was one of the first psychologists to apply psychology to advertising, management, and personnel selection. In 1903, Scott published two books: The Theory of Advertising and Psychology of Advertising. They are the first books to describe the use of psychology in the business world. By 1911 he published two more books, Influencing Men in Business and Increasing Human Efficiency in Business. In 1916 a newly formed division in the Carnegie Institute of Technology hired Scott to conduct applied research on employee selection (Katzell & Austin, 1992).

The focus of all this research was in what we now know as industrial psychology; it was only later in the century that the field of organizational psychology developed as an experimental science (Katzell & Austin, 1992). In addition to their academic positions, these researchers also worked directly for businesses as consultants.

When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, the work of psychologists working in this discipline expanded to include their contributions to military efforts. At that time Yerkes was the president of the 25-year-old American Psychological Association (APA). The APA is a professional association in the United States for clinical and research psychologists. Today the APA performs a number of functions including holding conferences, accrediting university degree programs, and publishing scientific journals. Yerkes organized a group under the Surgeon General’s Office (SGO) that developed methods for screening and selecting enlisted men. They developed the Army Alpha test to measure mental abilities. The Army Beta test was a non-verbal form of the test that was administered to illiterate and non-English-speaking draftees. Scott and Bingham organized a group under the Adjutant General’s Office (AGO) with the goal to develop selection methods for officers. They created a catalogue of occupational needs for the Army, essentially a job-description system and a system of performance ratings and occupational skill tests for officers (Katzell & Austin, 1992). After the war, work on personnel selection continued. For example, Millicent Pond researched the selection of factory workers, comparing the results of pre-employment tests with various indicators of job performance (Vinchur & Koppes, 2014).

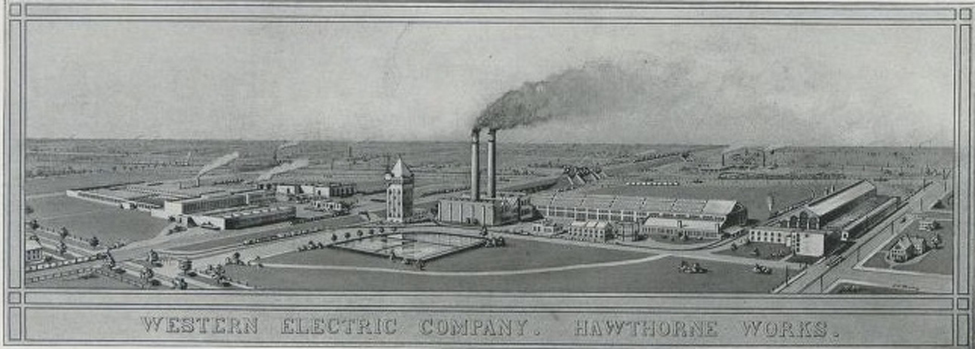

From 1929 to 1932 Elton Mayo (1880–1949) and his colleagues began a series of studies at a plant near Chicago, Western Electric’s Hawthorne Works (Figure 13.4). This long-term project took industrial psychology beyond just employee selection and placement to a study of more complex problems of interpersonal relations, motivation, and organizational dynamics. These studies mark the origin of organizational psychology. They began as research into the effects of the physical work environment (e.g., level of lighting in a factory), but the researchers found that the psychological and social factors in the factory were of more interest than the physical factors. These studies also examined how human interaction factors, such as supervisorial style, increased or decreased productivity.

In the 1930s, researchers began to study employees’ feelings about their jobs. Kurt Lewin also conducted research on the effects of various leadership styles, team structure, and team dynamics (Katzell & Austin, 1992). Lewin is considered the founder of social psychology and much of his work and that of his students produced results that had important influences in organizational psychology. Lewin and his students’ research included an important early study that used children to study the effect of leadership style on aggression, group dynamics, and satisfaction (Lewin, Lippitt, & White, 1939). Lewin was also responsible for coining the term group dynamics, and he was involved in studies of group interactions, cooperation, competition, and communication that bear on organizational psychology.

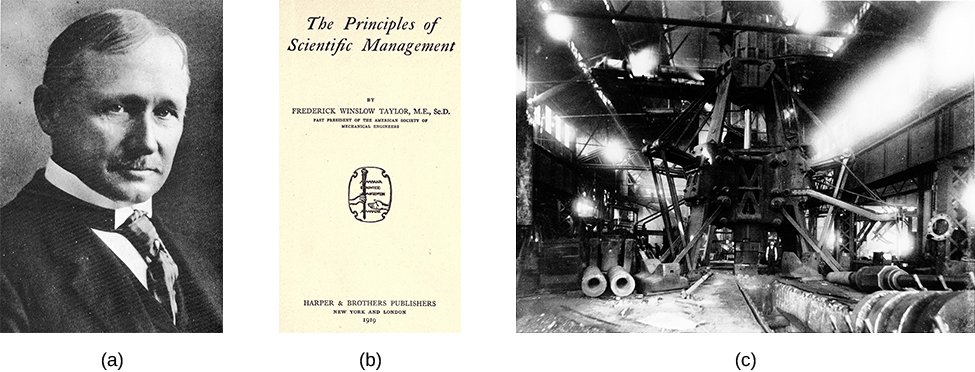

Parallel to these studies in industrial and organizational psychology, the field of human factors psychology was also developing. Frederick Taylor was an engineer who saw that if one could redesign the workplace there would be an increase in both output for the company and wages for the workers. In 1911 he put forward his theory in a book titled, The Principles of Scientific Management (Figure 13.6). His book examines management theories, personnel selection and training, as well as the work itself, using time and motion studies. Taylor argued that the principle goal of management should be to make the most money for the employer, along with the best outcome for the employee. He believed that the best outcome for the employee and management would be achieved through training and development so that each employee could provide the best work. He believed that by conducting time and motion studies for both the organization and the employee, the best interests of both were addressed. Time-motion studies were methods aimed to improve work by dividing different types of operations into sections that could be measured. These analyses were used to standardize work and to check the efficiency of people and equipment.

Personnel selection is a process used by recruiting personnel within the company to recruit and select the best candidates for the job. Training may need to be conducted depending on what skills the hired candidate has. Often companies will hire someone with the personality that fits in with others but who may be lacking in skills. Skills can be taught, but personality cannot be easily changed.

From WWII to Today

World War II also drove the expansion of industrial psychology. Bingham was hired as the chief psychologist for the War Department (now the Department of Defense) and developed new systems for job selection, classification, training, ad performance review, plus methods for team development, morale change, and attitude change (Katzell & Austin, 1992). Other countries, such as Canada and the United Kingdom, likewise saw growth in I-O psychology during World War II (McMillan, Stevens, & Kelloway, 2009). In the years after the war, both industrial psychology and organizational psychology became areas of significant research effort. Concerns about the fairness of employment tests arose, and the ethnic and gender biases in various tests were evaluated with mixed results. In addition, a great deal of research went into studying job satisfaction and employee motivation (Katzell & Austin, 1992).

The research and work of I-O psychologists in the areas of employee selection, placement, and performance appraisal became increasingly important in the 1960s. When Congress passed the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Title VII covered what is known as equal employment opportunity. This law protects employees against discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, as well as discrimination against an employee for associating with an individual in one of these categories.

Organizations had to adjust to the social, political, and legal climate of the Civil Rights movement, and these issues needed to be addressed by members of I/O in research and practice.

There are many reasons for organizations to be interested in I/O so that they can better understand the psychology of their workers, which in turn helps them understand how their organizations can become more productive and competitive. For example, most large organizations are now competing on a global level, and they need to understand how to motivate workers in order to achieve high productivity and efficiency. Most companies also have a diverse workforce and need to understand the psychological complexity of the people in these diverse backgrounds.

Today, I-O psychology is a diverse and deep field of research and practice, as you will learn about in the rest of this chapter. The Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (SIOP), a division of the APA, lists 8,000 members (SIOP, 2014) and the Bureau of Labor Statistics—U.S. Department of Labor (2013) has projected this profession will have the greatest growth of all job classifications in the 20 years following 2012. On average, a person with a master’s degree in industrial-organizational psychology will earn over $80,000 a year, while someone with a doctorate will earn over $110,000 a year (Khanna, Medsker, & Ginter, 2012).