4.5: Sexual Response

- Page ID

- 210790

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)4.5: Sexual Response

Sexual response is both biological and based on socialization factors. Each individual person has a natural degree to which they become aroused in response to sexual stimuli similar to how some people react more intensely to loud sounds or have a low to high pain tolerance. Life experiences across the lifespan continue to influence and change these as well. Individual differences in how sexual stimuli are experienced will influence the degree of desire to engage in certain sexual behaviors. Social factors, such as shame and stigma around certain sexual behaviors, can also influence this process by reworking the way that touch and sexual contact are perceived. In this section, we will look at different aspects of the nervous system that are implicated in this process, explore the groundbreaking Masters and Johnson research on the sexual response cycle, and discuss additional theories that have been developed over time that explore the ways the social environment interacts with sensory experiences.

Sex on the Brain

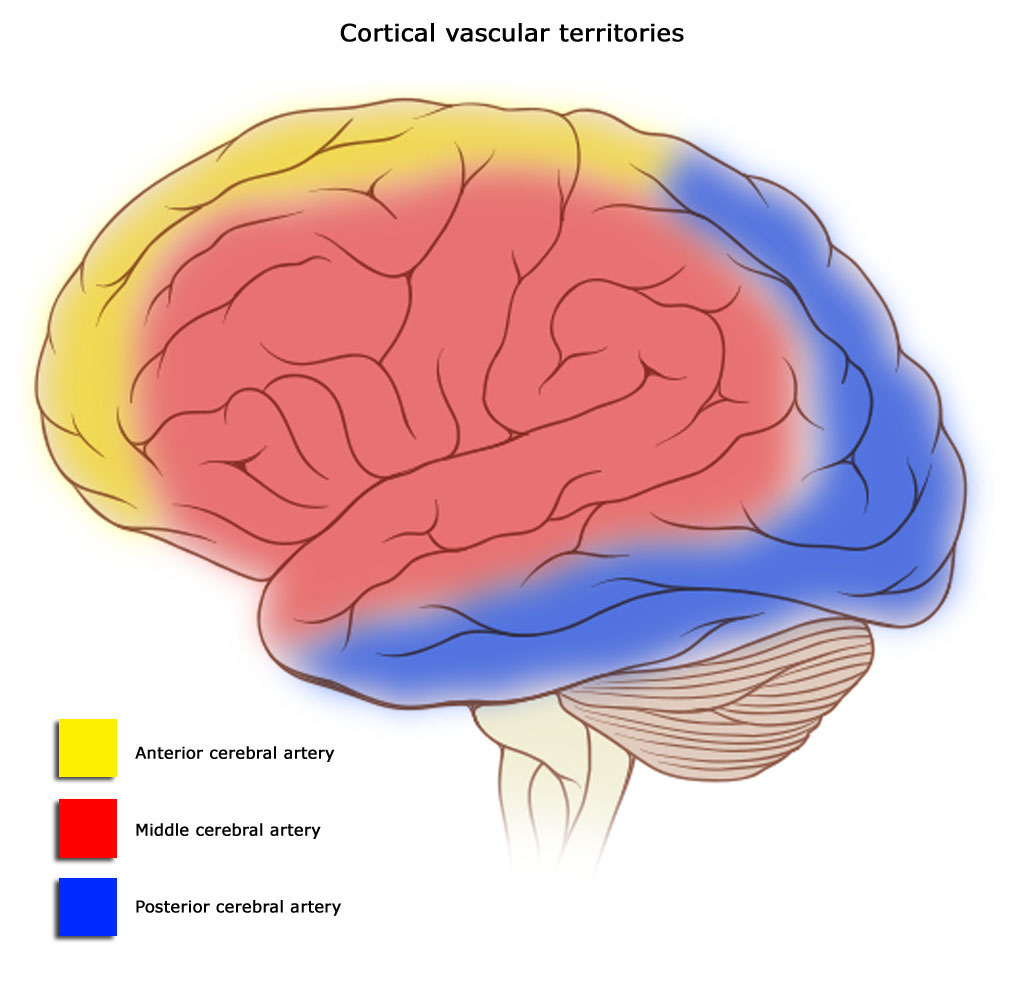

Figure 3: Some of the many regions of the brain and brainstem activated during pleasure experiences. [Image: Frank Gaillard, https://goo.gl/yCKuQ2, CC-BY-SA 3.0. Identifying marks added]

At first glance—or touch for that matter—the clitoris and penis are the parts of our anatomies that seem to bring the most pleasure. However, these two organs pale in comparison to our central nervous system’s capacity for pleasure. Extensive regions of the brain and brainstem are activated when a person experiences pleasure, including: the insula, temporal cortex, limbic system, nucleus accumbens, basal ganglia, superior parietal cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and cerebellum (see Figure 3, Ortigue et al., 2007). Neuroimaging techniques show that these regions of the brain are active when patients have spontaneous orgasms involving no direct stimulation of the skin (e.g., Fadul et al., 2005) and when experimental participants self-stimulate erogenous zones (e.g., Komisaruk et al., 2011). Erogenous zones are sensitive areas of skin that are connected, via the nervous system, to the somatosensory cortex in the brain.

Figure 4: Erogenous Zones Mapped on the Somatosensory Cortex.

The somatosensory cortex (SC) is the part of the brain primarily responsible for processing sensory information from the skin. The more sensitive an area of your skin is (e.g., your lips), the larger the corresponding area of the SC will be; the less sensitive an area of your skin is (e.g., your trunk), the smaller the corresponding area of the SC will be (see Figure 4, Penfield & Boldrey, 1937). When a sensitive area of a person’s body is touched, it is typically interpreted by the brain in one of three ways: “That tickles!” “That hurts!” or, “That…you need to do again!” Thus, the more sensitive areas of our bodies have greater potential to evoke pleasure. A study by Nummenmaa and his colleagues (2016) used a unique method to test this hypothesis. The Nummenmaa research team showed experimental participants images of same- and opposite-sex bodies. They then asked the participants to color the regions of the body that, when touched, they or members of the opposite sex would experience as sexually arousing while masturbating or having sex with a partner. Nummenmaa found the expected “hotspot” erogenous zones around the external sex organs, breasts, and anus, but also reported areas of the skin beyond these hotspots: “[T]actile stimulation of practically all bodily regions trigger sexual arousal….” Moreover, he concluded, “[H]aving sex with a partner…”—beyond the hotspots—“…reflects the role of touching in the maintenance of…pair bonds.”

Sensation and Perception

Sensation is the way the nervous system, such as different areas of the brain, processes sensory information from the environment, such as light, sound, smell, and touch/pain. Let’s take a look at touch in the context of sensual contact by explaining the process of transduction–receptors in the skin relay the message of being touched to transmitters in the spinal cord that converts this to neural signals interpreted by the brain which then allows effectors, neurons within muscles, to signal a response to the stimuli, such as by jerking away the hand when something is hot. Perception is how an individual associates meaning with what they are sensing. For instance, masturbation will cause the genital’s skin receptor sites and nervous system to respond to this sensation producing arousal; however, the self-talk regarding the morality of masturbation will impact the way the person perceives the arousal. Pay attention to the way that stigma and shame around pleasure and sensuality have influenced the way you attach meaning to your physiological experiences.

Exploring your erogenous zones: What areas of your body feel particularly pleasurable to the touch? Some common areas, apart from the genitals, are the lower back, inner thighs, lips, nipples, feet, hands, and more! Each individual will have specific areas so explore this question with your sexual partners as well.

Sensate focus is sometimes utilized within sex therapy to increase control over physiological responses and to provide insight into sexual partners’ pleasure points in addition to one’s own without touching or stimulating the genitals. Anxiety is experienced by many individuals as being sensual can feel very vulnerable and scary. Sensate focus uses aspects of cognitive-behavioral therapy and behavioral modification to focus on the senses and alter the meaning that has been associated with sexual interactions. Check out this article on sensate focus techniques from Cornell University (2019). These techniques can be utilized by anyone who is interested and can enhance sexual pleasure through increasing self-awareness and communication focused on pleasure with partners.

Hormones and Pheromones

Androgens, estrogen, and progestin bind to hormone receptor sites that allow the synthesis of neurochemicals (Hyde & DeLamater, 2017). During excitement and arousal, dopamine, oxytocin, and norepinephrine are released into the bloodstream, and during orgasm, opioids and endocannabinoids are released (Hyde & DeLamater, 2017). Hormones have activating effects in which they can activate and deactivate sexual arousal. Testosterone is particularly implicated in increasing desire for sex. Too high or too low of testosterone reduces desire. Intense emotions increase sexual arousal such as happiness, anger, anxiety, sadness, etc. because of their physiological impacts on our endocrine and nervous systems. For instance, sex and aggression both involve the hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine (which are also neurotransmitters) as they invoke a sense of excitement then resolution. This connection between emotions and our physiological reactions is a growing focus within research (Hyde & DeLamater, 2017).

While hormones are typically released within the bloodstream and influence sexual arousal, pheromones are biochemicals secreted outside the body that communicate to others on a chemical level about hormonal levels and ovulation which subconsciously attracts us to them based on our own body’s chemistry (Hyde & DeLamater, 2017). Researchers are still trying to understand the role of pheromones in sexual responses, but what is known is that when people are presented with the scent of others they are typically more attracted to the smell of someone in a way that matches with their sexual orientation even without any other information provided (Savic, 2014). Additionally, the scent of people who are biologically related is rated as less attractive and possibly connects to evolution protecting against unintentional incest (Savic, 2014). Animal studies on male monkeys indicate that they experience increases in testosterone when exposed to an ovulating female’s urine (Hyde & DeLamater, 2017). Pheromones are believed to influence the hormones in others and this can be seen by women’s menstrual cycles syncing up when they spend a lot of time with each other as well. This further showcases how interconnected humans are with one another biologically in addition to socially.

Theories and Models Regarding Sexual Response

Masters and Johnson

Although people have always had sex, the scientific study of it has remained taboo until relatively recently. In fact, the study of sexual anatomy, physiology, and behavior wasn’t formally undertaken until the late 19th century, and only began to be taken seriously as recently as the 1950’s. Notably, William Masters (1915-2001) and Virginia Johnson (1925-2013) formed a research team in 1957 that expanded studies of sexuality from merely asking people about their sex lives to measuring people’s anatomy and physiology while they were actually having sex. Masters was a former Navy lieutenant, married father of two, and trained gynecologist with an interest in studying prostitutes. Johnson was a former country music singer, single mother of two, three-time divorcee, and two-time college dropout with an interest in studying sociology. And yes, if it piques your curiosity, Masters and Johnson were lovers (when Masters was still married); they eventually married each other, but later divorced. Despite their colorful private lives they were dedicated researchers with an interest in understanding sex from a scientific perspective.

Masters and Johnson used primarily plethysmography (the measuring of changes in blood- or airflow to organs) to determine sexual responses in a wide range of body parts—breasts, skin, various muscle structures, bladder, rectum, external sex organs, and lungs—as well as measurements of people’s pulse and blood pressure. They measured more than 10,000 orgasms in 700 individuals (18 to 89 years of age), during sex with partners or alone. Masters and Johnson’s findings were initially published in two best-selling books: Human Sexual Response, 1966, and Human Sexual Inadequacy, 1970. Their initial experimental techniques and data form the bases of our contemporary understanding of sexual anatomy and physiology.

Physiology and the Sexual Response Cycle

The brain and other sex organs respond to sexual stimuli in a universal fashion known as the sexual response cycle (SRC; Masters & Johnson, 1966). The SRC is composed of four phases:

- Excitement: Activation of the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system defines the excitement phase; heart rate and breathing accelerates, along with increased blood flow to the penis, vaginal walls, clitoris, and nipples (vasocongestion). Involuntary muscular movements (myotonia), such as facial grimaces, also occur during this phase.

- Plateau: Blood flow, heart rate, and breathing intensify during the plateau phase. During this phase, often referred to as “foreplay,” females experience an orgasmic platform—the outer third of the vaginal walls tightening—and males experience a release of pre-seminal fluid containing healthy sperm cells (Killick et al., 2011). This early release of fluid makes penile withdrawal a relatively ineffective form of birth control (Aisch & Marsh, 2014). (Question: What do you call a couple who use the withdrawal method of birth control? Answer: Parents.)

- Orgasm: The shortest but most pleasurable phase is the orgasm phase. After reaching its climax, neuromuscular tension is released and the hormone oxytocin floods the bloodstream—facilitating emotional bonding. Although the rhythmic muscular contractions of an orgasm are temporally associated with ejaculation, this association is not necessary because orgasm and ejaculation are two separate physiological processes.

- Resolution: The body returns to a pre-aroused state in the resolution phase. Most males enter a refractory period of being unresponsive to sexual stimuli. The length of this period depends on age, frequency of recent sexual relations, level of intimacy with a partner, and novelty. Because most females do not have a refractory period, they have a greater potential—physiologically—of having multiple orgasms.

Of interest to note, the SRC occurs regardless of the type of sexual behavior—whether the behavior is masturbation; romantic kissing; or oral, vaginal, or anal sex (Masters & Johnson, 1966). Further, a partner or environmental object is sufficient, but not necessary, for the SRC to occur.

Kaplan’s Triphasic Model

Helen Singer Kaplan was a sex therapist seeking a model that would aid her in explaining the sexual response cycle to her clients. Kaplan adjusted Masters and Johnsons’ model by adding the desire phase and reduced excitement and plateau to just the excitement phase in which she focused on vasocongestion occurring. By focusing on the psychological and physiological processes more than trying to separate these experiences, her model became:

- Desire: Desire activates excitement and excitement can cause desire, motivating a person toward sexual activity. This phase is psychological while the next two are physiological.

- Arousal: Vasocongestion causes blood to flow to the genitals and increase in blood pressure and is controlled by the parasympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system (Hyde & DeLamater, 2017, p. 191)

- Orgasm: Reflex muscular contractions also involve anatomical structures and are connected to the nervous system. The ejaculation reflex can be controlled whereas the erection reflex typically cannot. Ejaculation and orgasm are controlled by the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system in order to return the body to homeostasis.

Unfortunately, Kaplan’s model did not seem to reflect women’s experience (Lieblum, 2000). Many women never experience spontaneous desire and for those who do, it does not always lead to sexual engagement or arousal. Furthermore, for many people, arousal occurs before desire. Finally, Kaplan’s model didn’t address sexual satisfaction (though her clinical work was built on that).

Basson’s Nonlinear Approach to Sexual Response

In response to to Masters & Johnson, linear model (where there is a start, a middle, and a finish line) and Kaplan’s incomplete model, Rosemary Basson articulated a more complex, circular model of sexual response. Basson’s circular diagram shows how sex is cyclical: desire often comes in response to something else, like a touch or an erotic conversation. If the sex is hot, even the fading memory of it could become motivation for more sex/arousal later on. Finally, sexual encounters don’t have to end with a mutual orgasm. They end with satisfaction, however a couple defines that, whether that’s five orgasms or none.

While this model was first conceptualized with female sexuality in mind, it’s applicable to all.

The Dual Control Model

This model was developed by former Kinsey Institute director Dr. John Bancroft and Dr. Erick Janssen in the late 1990s. It “proposes that two basic processes underlie human sexual response: excitation (responding with arousal to sexual stimuli) and inhibition (inhibiting sexual arousal)” (Hyde & DeLamater, 2017, p. 191). We have evolutionarily developed an inhibition aspect to the sexual response process to protect us from dying. Imagine you are in the middle of having sex and a dinosaur begins to run at you. Survival requires the ability to inhibit sexual arousal to focus on getting away to safety. Or, perhaps a more realistic example could be masturbating in the privacy of a bedroom when there is a sudden knock on the door and mom saying she is coming in. Mom is not a dinosaur but she is going to have that same inhibiting impact.

This perspective also explores the reason why some people may be more easily aroused by sexual stimuli while others may be less impacted. Every person has their own degree of excitation and inhibition similar to how each person has different tolerances for loud sounds or pain. If a person has high excitation and low inhibition, it may be easier for them to become aroused and take more time to return to homeostasis. Touch and sensations may be heightened and they may require less stimulation to reach orgasm. On the other hand, if someone has low excitation and high inhibition, sexual stimuli may be less arousing and they may require a broader range of sensual stimulation to achieve orgasm. Excitation and inhibition are negatively correlated with one another because as one increases the other decreases.

We are genetically predisposed to having a certain combination of sexual excitation and inhibition. However, the dual control model also recognizes that there are cognitive factors shaping this process. Our experiences impact the interpretation of the senses and can cause heightened distress or increased tolerance. Early learning and culture can then drastically shape someone’s excitation and inhibition combination. Many researchers liken it to having both a gas pedal (excitation or SES) and a brake pedal (inhibition or SIS) in a car – people will often engage one or both pedals to a differing degree in any particular sexual situation, depending on their unique sexual physiology, history, and personality.

In thinking about intersecting identities, how could generation, physical health, mental health, religion, education, family background, financial resources, body image, and more influence excitation and inhibition? What messages about various sexual behaviors have you internalized, and how might this influence your neurological sexual response? Having a conversation with your partners about their degree of excitation and inhibition can be helpful to know in relation to your own as well.

Attribution:

Introduction to Human Sexuality Copyright © 2022 by Ericka Goerling, PhD and Emerson Wolfe, MS is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.