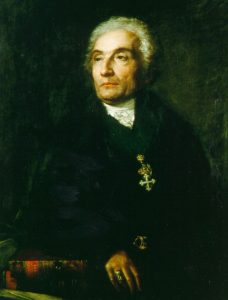

1.13: Joseph de Maistre — Excerpts from Study on Sovereignty, 1794

- Page ID

- 156386

Joseph de Maistre was a French writer, philosopher, and diplomat. Caught up in the turmoil and chaos of the French Revolution in 1789, de Maistre turned to conservative ideas of monarchy and hierarchy.

ON THE ORIGINS OF SOVEREIGNTY

…society is not the work of man, but the immediate result of the will of the Creator who has willed that man should be what he has always and everywhere been.

…SOVEREIGNTY IN GENERAL

…If sovereignty is not anterior to the people, at least these two ideas are collateral, since a sovereign is necessary to make a people. It is as impossible to imagine a human society, a people, without a sovereign as a hive and bees without a queen: for, by virtue of the eternal laws of nature, a swarm of bees exists in this way or it does not exist at all. Society and sovereignty are thus born together; it is impossible to separate these two ideas. Imagine an isolated man: there is no question of laws or government, since he is not a whole man and society does not yet exist. Put this man in contact with his fellowmen: from this moment you suppose a sovereign. The first man was king over his children; each isolated family was governed in the same way. But once these families joined, a sovereign was needed, and this sovereign made a people of them by giving them laws, since society exists only through the sovereign. Everyone knows the famous line,

The first king was a fortunate soldier.

This is perhaps one of the falsest claims that has ever been made. Quite the opposite could be said, that

The first soldier was paid by a king.

There was a people, some sort of civilization, and a sovereign as soon as men came into contact. The word people is a relative term that has no meaning divorced from the idea of sovereignty: for the idea of a people involves that of an aggregation around a common center, and without sovereignty there can be no political unity or cohesion…

…PARTICULAR SOVEREIGNTIES AND NATIONS

…The same power that has decreed social order and sovereignty has also decreed different modifications of sovereignty according to the different character of nations. Nations are born and die like individuals. Nations have fathers, in a very literal sense, and teachers commonly more famous than their fathers, although the greatest merit of these teachers is to penetrate the character of the infant nation and to create for it circumstances in which it can develop all its capacities.

Nations have a general soul and a true moral unity which makes them what they are. This unity is evidenced above all by language.

The Creator has traced on the globe the limits of nations…These boundaries are obvious and each nation can still be seen straining to fill entirely one of the areas within these boundaries. Sometimes invincible circumstances thrust two nations together and force them to mingle. Then their constituent principles penetrate each other and produce a hybrid nation which can be either more or less powerful and famous than if it was a pure race.

But several national elements thrown together into the same receptacle can be harmful. These seeds squeeze and stifle each other. The men who compose them, condemned to a certain moral and political mediocrity, will never attract the eyes of the world in spite of a large number of individual virtues, until some great shock, starting one of these seeds growing, allows it to engulf the other and to assimilate them into its own substance. Italiam! Italiam!

Sometimes a nation lives in the midst of another much more numerous, refuses to integrate because there is not sufficient affinity between them, and preserves its moral unity….

When one talks of the spirit of a nation, the expression is not so metaphorical as is believed.

From these different national characteristics are born the different modifications of governments. One can say that each government has its separate character, for even those which belong to the same group and carry the same name reveal subtle differences to the observer.

The same laws cannot suit different provinces which have different customs, live in opposite climates, and cannot accept the same form of government.

The general objects of every good institution must be modified in each country by the relationships which spring as much from the local situation as from the character of the inhabitants. It is on the basis of these relationships that each people should be assigned a particular institutional system, which is the best, not perhaps in itself, but for the state for which it is intended.

There is only one good government for a particular state; yet not only can different governments be suitable for different peoples; they can also be suitable for the same people at different times, since a thousand events can change the inner relationships of a people.

There has always been a great deal of discussion on the best form of government without consideration of the fact that each can be the best in some instances and the worst in others!

Therefore it should not be said that every form of government is appropriate to every country: for example, liberty, since it will not grow under every climate, is not open to every nation. The more one thinks about this principle laid down by Montesquieu, the more one feels its force. The more it is contested, the more strongly it is established by new proofs. Thus the absolute question, What is the best form of government? is as insoluble as it is indefinite; or, to put it another way, it has as many correct solutions as there are possible combinations in the relative and absolute positions of nations.

…THE FOUNDERS AND THE POLITICAL CONSTITUTION OF NATIONS

…Thinking about the moral unity of nations, there can be no doubt that it is the result of a single cause. What the wise Bonnet said about the animal body in answer to a fancy of Buffon can be said about the body politic: every seed is necessarily one; and it is always from a single man that each nation takes its dominant trait and its distinctive character.

To know, then, why and how a man literally engenders a nation, and how he passes on to them the moral temperament, the character, the general soul which must, over the course of centuries and an infinite number of generations, exist perceptibly and distinguish one nation from all others, this is a mystery like so many others on which it is fruitful to dwell…. The government of a nation is no more its own work than its language. Just as in nature the seeds of an infinite number of plants are destined to perish unless the wind or the hand of man puts them where they can germinate, so also there are in nations certain qualities and powers which are ineffective until they get a stimulus from circumstances either alone or used by a skillful hand.

…The founder of a nation is precisely this skillful hand. Gifted with an extraordinary penetration or, what is more probable, with an infallible instinct (for often personal genius does not realize what it is achieving, which is what distinguishes it above all from intelligence), he divines those hidden powers and qualities which shape a nation’s character, the means of bringing them to life, putting them into action, and making the greatest possible use of them. He is never to be seen writing or debating; his mode of acting derives from inspiration; and if sometimes he takes up a pen, it is not to argue but to command.

One of the greatest errors of this age is to believe that the political constitution oœ nations is the work of man alone and that a constitution can be made as a watchmaker makes a watch. This is quite false; but still more false is the belief that this great work can be executed by an assembly of men. The author of all things has only two ways of giving a government to a people. Most often he reserves to himself its formation more directly by making it grow, as it were, imperceptibly like a plant, through the conjunction of a multitude of those circumstances we call fortuitous. But when he wants to lay quickly the foundations of a political structure and to show the world a creation of this kind, he confides his power to rare men, the true Elect. Scattered thinly over the centuries, they rise like obelisks on time’s path, and, as humanity grows older, they appear the less. To fit them for these unusual tasks, God invests them with unusual power, often unknown to their contemporaries and perhaps to themselves. Bousseau himself has spoken the truth when he said that the work of the founder of a nation was a MISSION…. If the founders of nations, who were all prodigious men, were to come before our eyes and we were to recognize their genius and their power, instead of talking nonsensically of usurpation, fraud, and fanaticism, we would fall on our knees and our sterility would disappear before the sacred sign shining from their brows….

What is certain is that the constitution of a nation is never the product of deliberation.

Almost all the great legislators have been kings, and even those nations destined to be republics have been constituted by kings. They are the men who preside at the political establishment of nations and draw up their first fundamental laws….

Look at every one of the world’s constitutions, ancient and modern: you will see that now and again long experience has been able to point out some institutions capable of improving governments on the basis of their original constitution or of preventing abuses capable of altering their nature. It is possible to name the date and authors of these institutions, but you will notice that the real roots of government have remained the same and that it is impossible to show their origin, for the very simple reason that they are as old as the nations and that, not being the result of an agreement, there can be no trace of a convention which never existed.

…All known nations have been happy and powerful to the degree that they have faithfully obeyed this national mind, which is nothing other than the destruction of individual dogmas and the absolute and general rule of national dogmas, that is to say, useful prejudices. Once let everyone rely on his individual reason in religion, and you will see immediately the rise of anarchy of belief or the annihilation of religious sovereignty. Likewise, if each man makes himself the judge of the principles of government you will see immediately the rise of civil anarchy or the annihilation of political sovereignty. Government is a true religion; it has its dogmas, its mysteries, its priests; to submit it to individual discussion is to destroy it; it has life only through the national mind, that is to say, political faith, which is a creed. Man’s primary need is that his nascent reason should be curbed under a double yoke; it should be frustrated, and it should lose itself in the national mind, so that it changes its individual existence for another communal existence, just as a river which flows into the ocean still exists in the mass of water, but without name and distinct reality.

…What is patriotism? It is this national mind of which I am speaking; it is individual abnegation. Faith and patriotism are the two great thaumaturges of the world. Both are divine. All their actions are miracles. Do not talk to them of scrutiny, choice, discussion, for they will say that you blaspheme. They know only two words, submission and belief; with these two levers, they raise the world. Their very errors are sublime. These two infants of Heaven prove their origin to all by creating and conserving; and if they unite, join their forces and together take possession of a nation, they exalt it, make it divine and increase its power a hundredfold….

…MONARCHY

…It can be said in general that all men are born for monarchy. This form of government is the most ancient and the most universal….Monarchical government is so natural that, without realizing it, men identify it with sovereignty. They seem tacitly to agree that, wherever there is no king, there is no real sovereign….

Image Attribution:“Joseph de Maistre” by Carl Christian Vogel von Vogelstein, Wikimedia Commons is in the Public Domain