6: Music and Inclusion

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 86332

- Natalie Sarrazin

- The College at Brockport via OpenSUNY

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Chapter Summary. Allowing all children equal access to an art form is more difficult than it sounds. Social pressures, stereotypes, and changing attitudes and perspectives can inhibit inclusion and lead to exclusionary practice. This chapter addresses the issue of several types of musical inclusion, including music and gender, and music for children with autism, ADD/ADHD, learning and physical disabilities.

I. Gender in Music

Most of us never consider whether music is gendered, but any system that is part of a culture, even a musical one, is bound to include any general perceptions and values of the society as a whole.

What is gender? The term sex refers to the biological and physiological characteristics that define men and women, while gender refers to society’s constructed roles, expectations, behaviors, attitudes, and activities that it deems appropriate for men and women. Many of us can remember the first time we became aware of our gender. For some, it was an article of clothing that was too “boyish” or “girlish” to wear, while for others it was noticing certain behaviors such as preferring to play with trucks and cars rather than dolls, and realizing the societal expectations that encourage boys to play with trucks and cars. We incorporate gender into all aspects of our daily lives from a very early age onward, and can be socially uncomfortable if we are unsure of someone’s gender or have issues coming to understand our own.

Perceptions of the individual based on their gender and race influence all of us in all areas. We contextualize, filter, draw conclusions, and make inferences, in part, based on someone’s physical attributes. Many educators have studied the role of gender and how it affects teachers and teaching. For example, individual teachers may prefer one gender to another, but the entire educational system in general, favors girls’ learning styles and behaviors over that of boys. Grades are affected in addition to access to certain opportunities and promotion to leader- ship roles. Boys and girls may express different musical interests and abilities with girls showing self-confidence in literacy and music and boys showing confidence in sports and math, but teachers also discuss boys and girls musicality differently (Green, 1993).

Is music gendered? Music is highly gendered in ways that we might not even think about. Societies attribute masculinity to different genres of music, instruments, and what musicians should look like when performing. For example, genres like heavy metal and rock are gendered not only in the fact that male musicians dominate them, but also in that they are perceived as male-oriented in subject matter, with appeal to a male audience. Gender lines are not as straightforward as one might believe, however. In performance, there is a great deal of gender bending or borrowing that can occur. On stage, male musicians may co-opt female gendered attributes as part of a performance, such as Heavy or Hair Metal band members wearing long hair and make-up.

Musical instruments are also “gendered.” Our choices as to which instrument to play, in other words, are not entirely our own. Society, friends, and teachers, play a significant role in our music selection process. As a culture, and even as children, we have very particular notions of who should play what instruments, with children as young as three associating certain instruments with gender (Marshall and Shibazaki, 2012). In a 1981 study, Griswold & Chroback found that the harp, flute, and piccolo had high feminine ratings; the trumpet, string bass, and tuba had high masculine ratings.

As Lucy Green mentions above (1993), boys and girls have different musical interests, and teachers discuss musicality differently regarding boys and girls, and are likely to offer differences in opportunity, instrument selection, etc. For example, according to a 2008 study, girls are more likely to sing, while boys are more likely to play instruments such as bass guitar, trombone, and percussion. One interesting exception to boy’s dominance of percussion is that, participation in African drumming was far more egalitarian, with an equal number of boys and girls playing (Hallam, 2008, p. 11-13).

Activity 11A

Think about it

You might have an early memory when deciding what instrument to play in the school band or for lessons at home. Why did you decide on which instrument to play? Were you influenced by what instrument other girls or boys or professional musicians were playing? Did your parents or teachers encourage you in one direction or another?

II. Music Therapy and Healing

Throughout this book, we’ve learned about the many connections that music has on mental and emotional development. Music, is of course, more than entertainment, and affects the body directly through its sound vibrations. Our bodies are made up of many rhythms—the heart, respiratory system, our body’s energy, digestive systems etc. These vibrations result in something called entrainment, where our bodies try to sync up with the tempo of the music. Music can affect our heartbeat, blood pressure, and pulse rate, and reduce stress, anxiety and even depression.

The fact that the body and mind are so affected by music forms the basis for most music therapy. Music Therapy is defined as “A systematic process of intervention wherein the therapist helps the client to achieve health, using musical experiences and the relationships that develop through them as dynamic forces of change” (Bruscia, 1989, p. 47). “Musical experiences can include singing or vocalizing, playing various percussion and melodic instruments, and listening to music…Music therapists tap into the power of music to arouse emotions that can be used to motivate clients” (Pelliteri, 2000).

Music for Well-being and Learning

Music can be used to create any number of environments for children to flourish cognitively and developmentally. Music creates a general sense of well being, while creating a positive environment in which to learn, create, and function. For example, playing soft classical music, particularly Baroque music (Bach, Vivaldi, etc.) increases attention and the ability to concentrate, allowing the listener to work more productively.

Music also has a direct impact on the heart rate. The heart responds by beating more quickly when listening to faster tempos, and slower when listening to slower tempos. It also responds to dynamics (loud and soft) and to certain pitch frequencies.

Tempo and related activities.

Activity |

Music |

|

High energy activities

|

130 beats per minute

|

|

Medium energy activities

|

80–100 beats per minute

|

|

Lower energy activities

|

60–80 beats per minute

|

In addition to the beats per minute (tempo), the timbre, expression, and volume (dynamics) of a song also have an impact. For example, a loud orchestral piece, even if it has 60 beats per minute, will not aid the body into a calm state as well as a softer, more soothing piece with a few instruments. Low-pitched instruments such as drums impact the body with vibration and rhythm that influence body rhythms and movement, whereas higher-pitched frequencies such as flute and voice demand more attention and focus. Pieces such as Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring or Orff’s Carmina Burana, for example, would not be good choices as they are likely to promote agitation and frenetic activity rather than concentration and productivity.

Activity 11B

Try This

Go to a website such as Pandora (www.pandora.com), Stereomood (www.stereomood.com) or Spotify (www.spotify.com). Select different types of music and note down the general beats per minute using a watch or clock. Then take stock of your physical reactions. For example, how do you respond to the workout genre on Pandora? Does your heart rate increase? Are you able to concentrate with this type of music in the background? What about the easy listening genre?

Compare: Does the Music Therapy selection on the Mood/Relaxed channel on Spotify create the same physical reaction as any of the classical adagio selections suggested above? How about the Mood Booster channel? How does Stereomood compare in terms of changing your mood? Document any physical reactions you might have had.

III. Learning Disabilities, Special Needs Children, and Music

Any group of students has a wide range of abilities, and each child presents a unique challenge in terms of the best way to reach their maximum learning potential. Some students may be gifted or already familiar with the material, while others are challenged simply by the arrangement of the room. Some children, however, require more extensive modifications to the curriculum in order to succeed. Regardless of where you work, you are likely to be in a position where you will encounter students that require additional help.Music can greatly assist these children in a variety of ways, helping and nurturing them in learning and development.

- Special Needs

- Learning Disabilities

- Autism

- ADD or ADHD

- Behavior Problems

- Physical Disabilities

- Hearing Loss

- Visual Loss

The strategies outlined below can be used in any general music work with children, but are particularly helpful techniques aimed at aiding individuals with specific needs. Many of the techniques introduced in this textbook are used in music therapy and to treat Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD). Musical activities such as singing, singing/vocalization, instrument play, movement/dance, musical improvisation, songwriting/composition, and listening to music, are types of musical therapy interventions to assess and help individuals practice identified skills.

Assessing Appropriate Songs for Special Needs Children

As with selecting any material for any child, you will need to assess the particular needs of the student, including speech and developmental levels. If the child is pre-verbal or verbally limited, a simple song (limited lyrics, simple phrases) would be more appropriate than something complex.

Musical activities, including singing or playing instruments, can increase the self-esteem level of the child. Pamela Ott suggests asking the following questions when selecting material, keeping in mind that simply doing the activity successfully is one of the most important goals (Ott, 2011):

- Have I chosen an activity that will interest my child?

- Have I modified the activity to the appropriate level to ensure a successful experience?

- Am I prepared to modify the activity even more if it appears to be too difficult for my child?

- Will the music made by my child in this activity be pleasing to him?

- Have I praised my child for attempting the activity?

Often children require a well-structured day in which to work successfully. In addition to integrating music in the day, as discussed in the next chapter as well, music can also help to organize and structure the day for children who have trouble transitioning from activity to activity.

Possible uses for music throughout the day include:

- Organization

- Activity: lining up, cleaning up

- Aesthetic Purpose: motivation

- Transitions

- Activity: changing from one activity to another

- Aesthetic Purpose: change of mood, re-focus energy

- Rituals

- Activity: Greetings/Hello, goodbye, holiday music

- Aesthetic Purpose: Prepare students mentally, provides stability and repetition

- Interstitial

- Activity: Short break between two subjects or activities

- Aesthetic Purpose: Provide relaxation, moment of expression, and alternate uses for cognitive functioning

Sample Day that includes Music

- Use music before the school day begins

- Ritual: Set the mood/change the atmosphere in the room using sound

- Students enter and settle in to the room

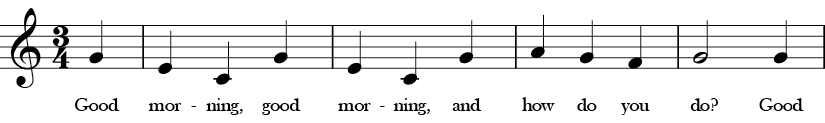

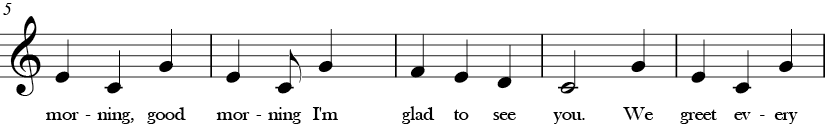

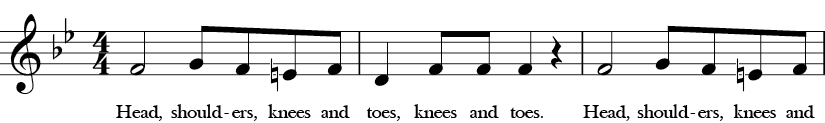

- Ritual: “Good Morning,” and/or movement activity “Head Shoulders”

- Morning Work, Attendance, Calendar

- Organization: i.e. “If you’re ready for P.E. line on up, line on up.”

- Special (Music, Art, Physical Ed)

- Transition: Focus for Math

- Math Stations

- Organization: Line up for Lunch

- Lunch

- Transition: Focus ready for reading

- Reading/Literacy Stations

- Interstitial: Break song/movement

- Writing

- Interstitial: Movement/song break

- Social Studies/Science/Health

- Transition: Movement activity/song

- Snack/Play time

- Organization: Focus: Line up for Library or Lab

- Computer Lab or Library

- Transition:

- Pickup and pack-up

- Organization: “Clean up song”

- Dismissal

- Ritual: “Goodbye” song

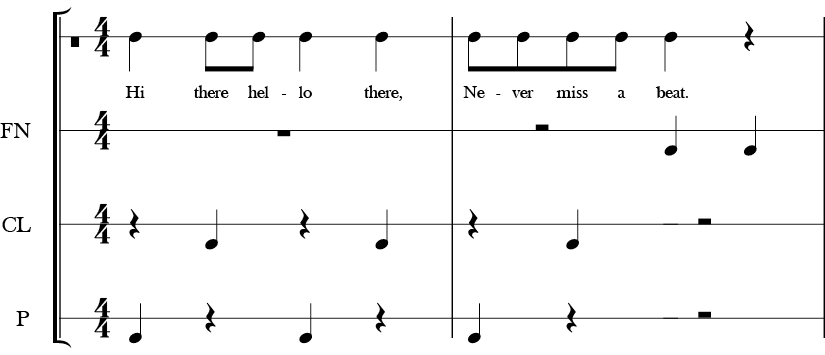

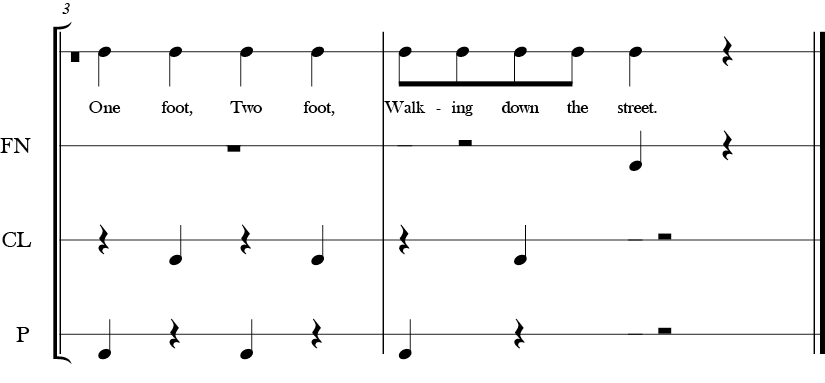

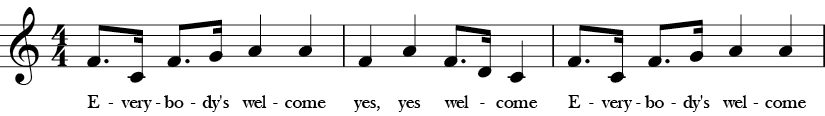

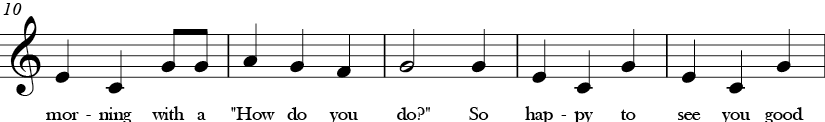

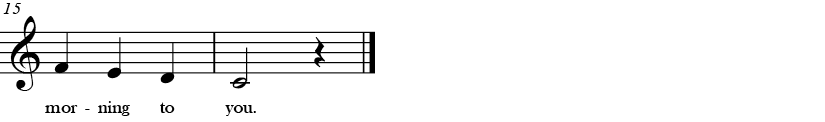

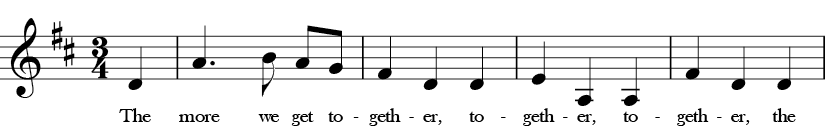

Examples of Hello rhymes and songs might include “Hi There, Hello There.” If the body percussion is too complex, simply say the rhyme or clap to the rhyme.

Hi There, Hello There

Good Morning

Everybody’s Welcome

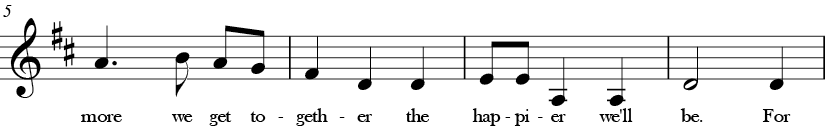

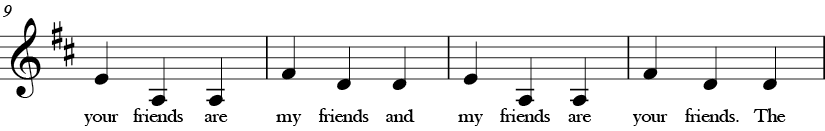

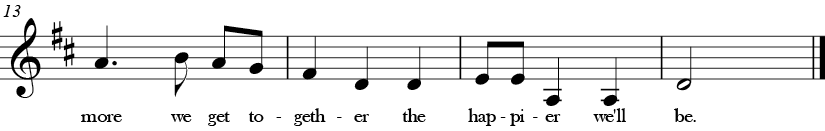

The More We Get Together

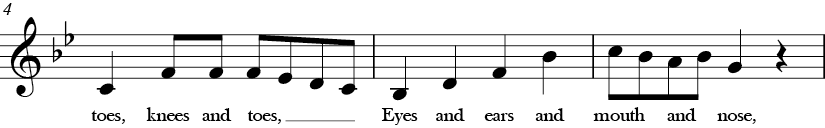

Head and Shoulders (Key of B flat)

Strategies and Songs for Enhancing and Encouraging Verbal Skills

For children who are pre-verbal or speech-delayed, substituting nonsense syllables helps them successfully sing a favorite tune. “Doo,” “boo,” “la,” etc., are easily pronounceable and fun for children to articulate.

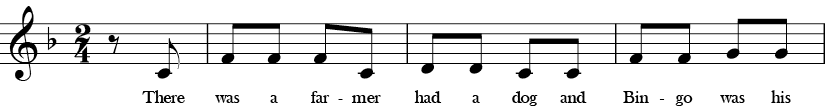

Other familiar songs to help increase verbal awareness include songs with word sub- stitutions or nonsense syllables such as Sarasponda or Supercalifragilisticexpialidocous. The song B-I-N-G-O is an excellent example in which to practice internalizing the pitch since the singer has to clap the rhythm and silently think the pitch in their head.

B-I-N-G-O

American play party song

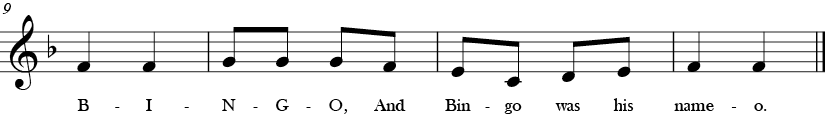

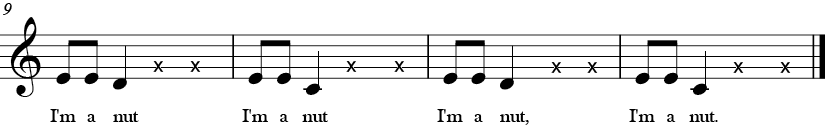

Another song with an opportunity for children to insert a rhythm is “I’m a Nut.” Although the song does have quite a few words, the refrain is repetitive with only three words, and provides two empty beats for clapping or playing an instrument.

I’m a Nut

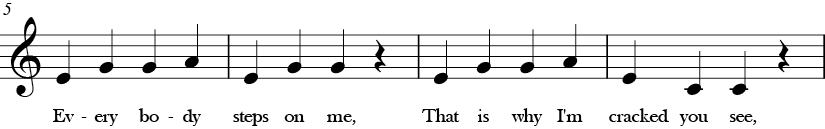

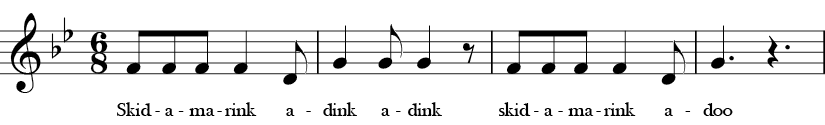

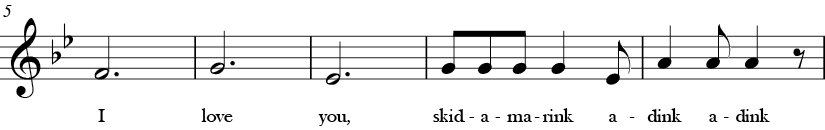

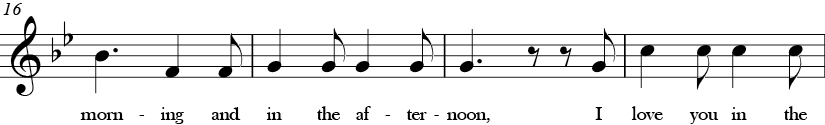

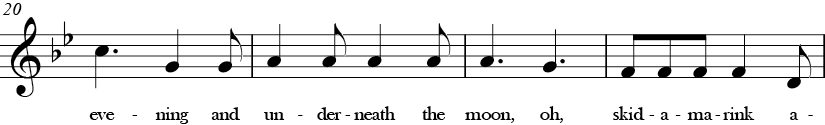

Any song can be adapted to allow the insertion of rhythm simply by substituting a word or phrase with a clap (or instrument). The substituted word or phrase can be part of the rhyme or not. For example, in the silly song “Skidamarink,” the phrase “I love you” can be clapped, or even just the “you.” Words such as “morning” “afternoon” “moon,” etc. are also good candidates for substitution.

Skidamarink

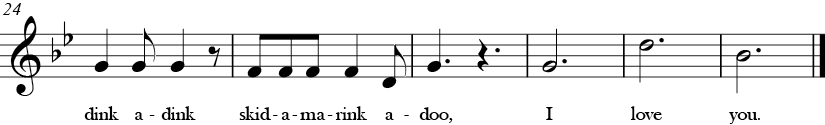

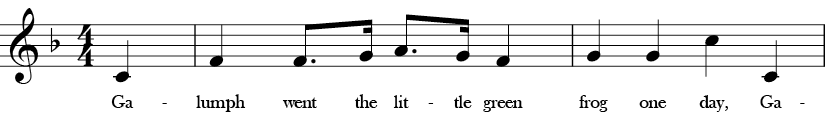

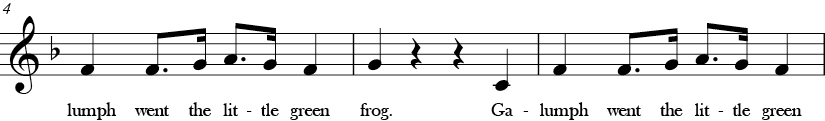

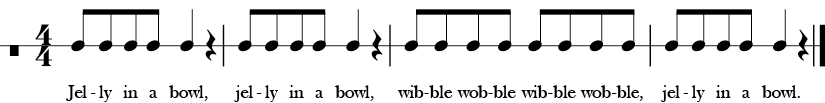

Silly songs and rhymes with interesting onomatopoeic sounds and simple, repetitive words are also highly useful, such as “Galumph Went the Little Green Frog” and “Jelly in a Bowl.”

Galumph Went the Little Green Frog One Day

Jelly in a Bowl

The remainder of the chapter contains material from the National Association for Music Educators regarding some tips and general strategies for working with children who have special needs.1

Music for Special Needs and Learning Disabilities

Many classrooms today are inclusive, meaning that they will include children who have special needs. Preparing to help these children requires additional thought and strategies.

General Strategies for Students with Special Needs

Avoid sensory overload and be predictable.

- Keep your classroom organized and free from distractions.

- Keep directions simple and direct.

- Establish lesson routines (e.g., beginning and ending songs).

Lesson preparation

- Present materials in as many modes as possible to address different learning styles.

- Develop a hands-on, participatory program that emphasizes varied activities like movement, instruments, rhythm, speech, sound exploration, melody, and dance for best effect.

Strategies for students with learning disabilities

Students who have difficulty reading

- Prepare simple visual charts.

- Use color to highlight key concepts (e.g., do=blue, re=red, mi=green).

- Isolate rhythm patterns into small pieces on a large visual.

- Indicate phrases with a change in color.

- Introduce concepts in small chunks.

- Use repetition, but present material in different ways.

Students with visual impairments

- Teach songs by rote and echoing patterns.

- Provide rhythm instruments—such students can learn to play them without problems.

- Assign a movement partner for movement activities.

- Read aloud any information you present visually.

- Get large-print scores when available.

- Give a tour of the room so students can become familiar with where things are.

Students with behavior problems

- Use routine and structure—it can be comforting for these students.

- Remain calm and don’t lose your temper.

- Maintain a routine from lesson to lesson (e.g., begin and end with a familiar song).

- Vary the drill by playing or singing with different articulation and dynamics for students who can’t maintain focus for long.

- Use props like puppets to give directions in a nonthreatening way.

- Use songs or games that contain directions to help children who struggle to follow verbal directions or who have authority issues.

Students with physical disabilities (e.g., cystic fibrosis, heart trouble, asthma, diabetes, epilepsy)

- Have students sing to help breathing and lung control.

- Adapt Orff instruments by removing bars so that any note played will be correct. Orff instruments fit nicely onto a wheelchair tray.

- Acquire adaptive instruments—adaptive mallets, Velcro straps for hand drums and other percussion instruments, and one-handed recorders are available. Find other adaptive musical instruments with an Internet search.

- Develop activities for listening and responding to recorded music for children who are physically unable to move and/or play an instrument.

Students with higher learning potential

- Offer a variety of activities, such as acceleration (design assignments that allow students to go to differing levels), enrichment (extra lessons), technological instruction (computer programs for composition, research, or theory).

- Find a mentor for a student.

- Offer advanced ability ensembles.

Debrot (2002) says you can address a variety of skill levels in one piece of music: While some children play complex patterns, others can sing or play a simple steady beat. “Every student has a learning style that is unique,” says Debrot. “Presenting material aurally, visually, tactilely, and orally will insure that you connect with the varied learning styles for all students. The use of speech, movement, instruments, and singing in each lesson will insure that each child feels some degree of success.”

Music and Autism

Music has been found to be successful in working with children who have Autistic Spectrum Disorder. Using music activities and songs helps to greatly increase independent performance and reduce anxiety. Music was found to help reduce the stress of transitions such as the shift from home to school, help children remember step-by-step routines like clean up time, and also increase the community and group inclusion of children with and without disabilities (Kern, 2004).

Iseminger (2009) refers to employing an “Intentional Approach” when dealing with students on the autism spectrum, particularly those with difficulty with transitions. The following examples are helpful in preparing autistic students in advance for transitions.

- To ease a transition from an Autoharp unit to a recorder unit, make an announcement (“Today is the last day for Autoharp because next week we begin playing the recorder.”), and put a visual clue on a large calendar (e.g., “Last day for Autoharp” or “Autoharp STOP,” “First day for recorders” or “Recorders YES”).

- To show a DVD (e.g., The Nutcracker in December), put a picture of the DVD or a TV on the calendar for that date at least a week ahead of time.

- To prepare for a concert dress rehearsal, post a picture of risers or the children standing on risers on that date.

- When the class is finished working on a song, put it in an “All Done” folder to show that the class won’t be working on it anymore.

- Write a short, simple picture story for the autistic child to read during the week preceding the major changes.

- Keep the number of changes to a minimum. Following a concert, introduce new songs slowly after reviewing the choir’s favorite song from the concert. Finish with a familiar song.

Shore’s work (2002) explains the musical benefits for those on the autism spectrum. Music provides an alternative means of communication for nonverbal students, and can also help other verbal students organize their communication. Music can help to improve children’s self-esteem in that they can participate and possibly excel in the musical endeavor. Music is also a social and communal activity, and a child with autism can enter into the communal and social interaction of music making.

Success with Autism: Visual Aids and Predictability2

Iseminger (2009) notes that two main areas where teachers can help students with autism are in creating appropriate visual aids and achieving predictability. “Children with special needs are concrete learners, and visual information makes words more concrete. Pictures of a student sitting in a chair or playing the recorder give clear directions. Those on the autism spectrum are often stronger visual than auditory learners and have a tremendous need for visual information.” Also, autistic children act out due to increased anxiety and fear, not from autism itself. As a classroom teacher, taking steps to minimize anxiety will help with managing classroom behavior.

Most teachers use some type of visual cues and supports such as charts, books, musical instruments, and music notation. Making these visuals simple and accessible will greatly help autistic children in the class.

- Use rhythm notation and beat icons to make rhythm a visual event. Point to four quarter notes or four icons while the class pats a steady beat.

- Show a picture of a recorder with correct fingering rather than a fingering chart.

- Clarify lyrics with pictures made from design software (e.g., Boardmaker), or decorate counting songs with pictures of each number and object.

- Post your lesson plan. List song titles to cross out or erase as they’re completed. Or make a tab system with pictures and Velcro or magnets. As each song or activity is completed, you or the child can pull off the tab and put it in a folder marked “All done.”

Managing Behavior

- To reward positive behavior: For a 30-minute class, prepare a file folder with a Velcro strip with the numbers 1 through 6. At the end of the strip, post a picture of a reward (e.g., favorite book or swing on the playground). For every 5 minutes the child follows directions and stays on task, she earns a star-shaped tab. When she sees all six tabs in place, she knows 30 minutes are done, and she gets her reward.

- To establish negative consequences: Prepare a card with 3 square tabs. At the first verbal warning, remove the first tab; repeat for a second infraction. Removing the last tab means removal from the classroom or other appropriate consequence.

Tips for creating predictability

Physical Structure

- Establish a seating arrangement, and keep it the same all year.

- Assign the student to an appropriate-size chair, carpet square, or a masking tape outline on the floor.

- For a child who can’t sit still, assign two chairs across the room from each other. Have her alternate chairs for each activity, providing the movement she craves.

- For a child who refuses to sit in a chair, photograph him sitting in his chair and sitting on a carpet square. Post both photos, and ask him to choose between them when entering music class. He gets a sense of control, yet you prescribe the limits.

Routine Structure

- Keep the structure of your lessons the same from session to session. For example, begin with a fun rhythm activity to get students going, and finish with a quiet relaxing or listening activity to calm them. The exact song or activity may vary, but the basic nature of the activity is the same and predictable.

- Establish your music routine the first day of class as a whole experience. Children with autism will show signs of discomfort or distress because they don’t know the routine. If you can overlook and tolerate some obvious distress and complete the lesson, the child will have experienced the entire routine and established it mentally. On the second day, she’ll likely show fewer signs of distress because now she knows what to expect. If a child shows severe aggression, obviously this can’t be ignored.

- If a child is unlikely to tolerate an entire first class, introduce him to music class for short periods, starting with the ending routine, or the last 5 minutes of class. After several successful 5-minute sessions, he can come in for the activity preceding the final activity, and so on, until he’s in music class for the full period. (This also works for a child already in class who’s struggling and feeling overwhelmed.)

“Sometimes you just have to plow through the struggle or upset to establish the routine,” says Iseminger. “They are taking it in, despite what it looks like, calming down after one or two class sessions.”

Students with ADD or ADHD3

Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are two of the most common factors for special needs in today’s classrooms. ADD and ADHD are disabilities and fall under the designating category of “Other Health Impairment.” This NAfME post addresses both issues and gives guidance to mediate its effects in the classroom.

Many teachers recognize the signs of attention deficit disorder (ADD) and attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD): an inability to maintain attention, impulsive behaviors, and/or motor restlessness. Students can have mild, moderate, or severe symptoms and can be found in both general education and special education classes.

Elise S. Sobol teaches at Rosemary Kennedy School, Wantagh, New York (for students with multiple learning disabilities, including those with autism and developmental difficulties) and is the chairperson of Music for Special Learners of the New York State School Music Association.

Sobol (2008) suggests the following strategies for students with ADD with or without hyperactivity:

- Teach and consistently reinforce social skills.

- Mediate asking questions.

- Define and redefine expectations.

- Assess understanding of content.

- Define and redefine appropriateness and inappropriateness.

- Make connections explicitly clear.

- Take nothing for granted.

- Reinforce positive behavior.

- Define benefits of completing a task.

- Include 21st-century relevance.

- Clearly mark music scores with clues to recall rehearsal information.

- Establish support through creative seating to enhance student security.

- Post your rehearsal plan.

- Repeat realistic expectations each session.

- Choose a repertoire that enhances character development and self-esteem.

- Use lots of rehearsals to embed information into short term memory.

- Be informed if a student takes medication to help regulate impulsive responses. Plan student participation accordingly.

- Follow classroom and performance program structure strictly so students know the sequence “first,” “then.”

Sobol subscribes to William Glasser’s Choice Theory: Students will do well if four basic needs are addressed in the educational classroom or performance setting. All students need to feel a sense of:

- Belonging—feeling accepted and welcome.

- Gaining power—growing in knowledge and skill and gaining self-esteem through successful mastery of an activity via realistic teacher direction.

- Having fun—improving health, building positive relationships, and enhancing thinking. Students need to be uplifted and spirited to add to the quality of their successful program.

- Being free—making good choices and expressing control over one’s life. Students need to be a part of their educational process. Each student gains importance and dignity as he or she participates in teaching and learning to set goals, make plans, choose behaviors, evaluate results, and learn from each experience to do things better.

Teaching Students with Behavior Problems4

“Students with behavior disorders are generally unhappy individuals, and they often make everyone around them unhappy as well,” says NAfME member Alice-Ann Darrow (2006) “They’re generally disliked by their peers, their teachers, their siblings, and often even their parents.” They may also be diagnosed with learning disabilities, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorders, depression, and suicidal tendencies.

Darrow recommends some instruction accommodations:

- Seat these students close to the teacher and beside model students.

- Plan learning activities that are motivating and desirable. Students become disruptive when they’re not actively engaged.

- Give clear, uncomplicated directions. Students often misbehave when they’re confused about what they’re supposed to do.

- Use the student’s name and look at him or her. Students misbehave more often when they feel anonymous.

- Define expectations for classroom behavior and be consistent in administering consequences.

- Make a desirable activity contingent upon completing a less desirable activity. Keep a list of desirable activities such as listening to CDs or playing music Bingo.

- Think “do” instead of “don’t.” Make a positive request (“Watch me”) rather than a negative one (“Don’t bury your head in the music”).

- Think “approval” instead of “disapproval.” Reinforce a student who’s doing what you want rather than admonishing a student who’s misbehaving.

- Find opportunities for problem students to behave appropriately and feel good about themselves. Ask them to help move risers or put instruments away so you can reinforce good behavior.

Darrow also uses strategies from Teaching Discipline by Madsen and Madsen (1998):

- Avoid labeling students—they often live up to the label.

- Reserve emotions.

- Choose your battles—prioritize which behaviors are most disruptive and will receive your time and attention.

- Use peers for tutoring or as part of your management strategies. Problem students often respond better to peer approval/disapproval. Peers can redirect students’ attention when they’re off-task or ignore attention-getting behaviors.

- Analyze problem situations—what are their trigger events, and what consequences extinguish or reinforce the problem behavior?

Adapting Instruction, Expectations, and Attitude

Adapt your expectations of students and your instruction. “Appropriate behaviors have to be shaped—shaped through successive approximations to the desired behavior,” says Darrow. “Shaping desired behaviors takes time.” When starting, she recommends accepting and reinforcing behaviors that come close to the desired behavior.

Developing more positive attitudes about teaching students with behavior disorders goes a long way to reduce the stress of teaching them.

Music and Students with Physical Disabilities5

More students with physical disabilities, orthopedic conditions, and fragile health are participating in school music programs. Elise Sobol, chairperson of Music for Special Learners of the New York State School Music Association, offers some advice:

Assistive Technology

“Technological advances such as the innovative SoundBeam,” says Sobol, “allow 100% accessibility to students with even the most severe limitations to experience the joy of making music, exploring sound, creating compositions, and performing expressively.”

The British SoundBeam system translates body movement into digitally generated sound and image. This technology is available in the U.S. through SoundTree. Click on “Music Education,” then on “Music Therapy.”

“Although it may be challenging for teachers to find adaptive instruments to suit the individual needs of their students,” Sobol says, “the music market catalog offerings are expanding.” See distributors such as West Music, Music Is Elementary, Musician’s Friend, among others.

Instructional Strategies

Sobol finds the following helpful:

- Make sure the class content will support students’ IEP requirements.

- Build motor skills (through consultation with goals of assigned occupational and physical therapists).

- Enhance vitality by building self-esteem through music.

- Design lessons that build on reduced or limited strength.

- Ensure accessibility to and inside classroom or performance space.

- Make the environment safe and secure. Organize instruments, props, AV equipment, etc. to permit wheelchair access. Intercom allows calling for help in case of a health alert.

- Always follow school policies for universal precautions and protections against infection.

- If a paraprofessional or teacher aide is not assigned to a specific student, use a buddy system.

- Assess student capability—what a student can do—and adapt musical instruments with materials such as Velcro (e.g. to hold a triangle on the wrist) to enhance student’s ability to play. Design, create, and invent for individual and unique situations.

Books to Read Aloud

Sobol has found success with the following:

- Knockin’ on Wood: Starring Peg Leg Bates, by Lynne Barasch—Inspirational. For building disability awareness and as an educational tool for success in the performing arts.

- Puppies for Sale by Dan Clark—About a puppy with a missing hip socket and a boy with a leg brace, it promotes positive character development.

- What’s Wrong with Timmy? by Maria Shriver—About a child with disabilities and forming new friendships.

- I Am Potential: Eight Lessons on Living, Loving, and Reaching Your Dreams by Patrick Henry Hughes and Patrick John Hughes—Born without eyes and malformed limbs, Patrick became a member of the marching band at the University of Louisville.

Music and Students with Hearing Loss6

Students who are deaf or hard of hearing can succeed in music class. MENC member Elise Sobol shares some of her instructional strategies.

- First and foremost, follow the student’s Individualized Education Program (IEP) for instructional adaptations. If the student has an educational or sign language interpreter, work closely with the interpreter for optimal success.

- Second, face the student so that eyebrow and lip-mouth movements are clear.

The following suggestions may also be helpful:

- Position student near the sound source for best amplification. Being near an acoustic instrument or speakers offers the greatest benefit from the sound. A hands-on experience is best, especially if the student is deaf.

- If the student has an FM amplifier system, make sure to position your microphone so the student can hear you. As newer assistive listening devices develop, be sure to receive training on them.

- Select instruments appropriate to the student’s range of resonant hearing with a sustaining quality. Match instruments to students’ functional independence and enjoyment.

- Use visual aids. “Give all lessons an auditory/visual/tactile/kinesthetic component to support contextual learning for students of all challenges,” Sobol says. “Visual strategies are most significant to students whose hearing is compromised. It’s their primary means for receiving information.” Written material, music notation, and color-coded charts and diagrams on overhead projectors or SMART Boards enhance teaching and learning.

- Use signing. “Music teachers naturally use gestures to indicate musical meaning in demonstrating dynamics, tempo, entrances/exits, standing up/sitting down, etc.,” Sobol says. “Learning basic finger spelling to enhance musical activities with pitch and using sign language to enhance a song performance is very helpful. Sign language is a beautiful way to communicate; all students will benefit.”

- Demonstrate the characteristics of the music and support lesson content with movement.

- Use Windows Media Player for recorded music. It dramatizes sound with unique artistic rhythm and design.

- Choose instruments that are held close to the body (e.g., guitar, sitar, violin, viola, cello, and bass are held against the body) so students can feel the resonance of the instrument as well as the sound vibrations. Some percussion or wind instruments fit the bill as well.

- Use a keyboard that lights to sound or touch to make the music visual.

Music and Students with Vision Loss7

Visual impairments range from low vision to blindness and can demand a variety of strategies. MENC member Elise Sobol urges educators to work closely with the special education team in their school district including the assigned vision teacher where applicable, and consult the student’s Individual Educational Program (IEP) to match any and all accommodations and learning supports.

These supports may include an assistive device such as a cane, technology and transcription software such as a Braille printer to translate text and music, a therapy animal such as a seeing-eye dog, or a teacher aide, depending on the student’s educational needs.

Instructional Strategies

Sobol has had success with the following:

- Make the music room accessible and free of floor wires for sound equipment, etc.

- Seat students in the front of the room and away from potential glare.

- Enlarge print per individual student needs. Lighthouse International recommends 16 to 18 point font depending upon typefaces.

- Use contrasting colors; white on black is more readable than black on white.

- Use tactile props in classroom music. Keep them simple and proof them with your fingers, not your eyes. Try different texture materials, rough like sandpaper, raised like playdough and pom-poms, or pipe cleaners—check art supply stores for variety to suit lesson plan.

- Use audio enhancement for visual directions.

- Enhance memory with sequential learning.

- Record parts and lessons on MP3/CD/tape for classroom focus and home practice.

- Keep a consistent classroom set up with good lighting so the student can make a mental map of the classroom. Notify student of and describe any changes made to the classroom.

- Above all create safety in space and place for music learning and fun.

Books to Read Aloud

Sobol recommends reading the following in the classroom:

- A Picture Book of Louis Braille by David Adler—Braille became blind at the age of 4 and learned to play the organ, violin, and cello.

- Knots on a Counting Rope by John Archambault and Bill Martin Jr.—A moving story of a Native American who was born blind and had a special mission.

- Helen Keller: Courage in the Dark by Johanna Hurwitz—The story of her indomitable will and devoted teacher.

- I Am Potential: Eight Lessons on Living, Loving, and Reaching Your Dreams by Patrick Henry Hughes and Patrick John Hughes—Born without eyes and malformed limbs, Patrick became a member of the marching band at the University of Louisville.

- Biographies of musician role models such as Ray Charles, Stevie Wonder, José Feliciano, and Nobuyuki Tsujii (Gold medal winner, Van Cliburn Competition).

References

Gender

Alden, A. (1998). What does it all mean? The National Curriculum for Music in a multi-cultural society. (Unpublished MA dissertation). London University Institute of Education, London.

Armstrong, V. (2011). Technology and the gendering of music education. Aldershot, U.K.: Ashgate.

Davidson, J. and Edgar, R. (2003). Gender and race bias in the judgment of Western art music performance. Music Education Research, 5(2), 169-181.

Eccles, J., Wigfield, A., Harold, R., & Blumenfeld, P. (1993). Age and ender differences in children’s self- and task perceptions during elementary school. Child Development, 64(3), 830-847.

Green, L. (1993). Music, gender and education: A report on some exploratory research. British Journal of Music Education, 10(3), 219-253.

Green, L. (1997). Music Education and Gender. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Green, L. (1999). Research in the sociology of music education: Some introductory concepts. Music Education Research, 1(1), 159-70.

Griswold, P., & Chroback, D. (1981). Sex-role associations of music instruments and occupations by gender and major. Journal of Research in Music Education, 29(1), 57-62.

Hallam, S. (2004). Sex differences in the factors which predict musical attainment in school aged students. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education,

161/162, 107-115.

Hallam, S., Rogers, L. Creech, A. (2008). Gender differences in musical instrument choice. International Journal of Music Education. 26 (1), 7-19.

Marshall, N., & Shibazaki, K. (2012). Instrument, gender and musical style associations in young children. Psychology of Music, 40(4), 494-507.

O’Neill, S. A.,Hargreaves, D. J., & North, A. C. (Eds.) (1997). The social psychology of music. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Autism

Iseminger, S. (2009). Keys to success with autistic children: Structure, predictability, and consistency are essential for students on the autism spectrum. Teaching Music, 16(6), 28.

Kern, P. (2004). “Making friends in music: Including children with autism in an interactive play setting. Music Therapy Today, 6(4), 563-595.

Shore, S. M. (2002). The language of music: Working with children on the autism spectrum. Journal of Education, 183(2), 97-108.

Hourigan, R. (2009). Teaching music to children with autism: Understandings and perspectives. Music Educators Journal, 96, 40-45.

Music Therapy and Healing

Bruscia, K. (1989). Defining music therapy. Spring Lake, PA: Spring House Books.

Eagle, C. (1978). Music psychology index. Denton, TX: Institute for Therapeutic Research.

Campbell, D., & Doman, A. (2012). Healing at the speed of sound: How what we hear transforms our brains and our lives. New York, NY:Plume Reprints.

Campbell, D. (2001). The Mozart effect: Tapping the power of music to heal the body, strengthen the mind, and unlock the creative spirit. New York: Quill.

Debrot, R. A. (2002). Spotlight on making music with special learners: Differentiating Instruction in the Music Classroom. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education.

Hodges, D. A. (Ed.). (1980). Handbook of music psychology. Dubuque, IA: National Association for Music Therapy.

Ott, P. (2011). Music for special kids. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Pelliteri, J. (2000). Music therapy in the special education setting. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 11(3/4), 379-91. Retrieved from http://www.soundconnectionsmt.com/docs/Music%20Therapy%20in%20Special%20Education.pdf

Sobol, E. (2008). An attitude and approach for teaching music to special learners. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Hourigan, R. (2008). Teaching strategies for performers with special needs. Teaching Music 15(6), 26.

Hourigan, R, and Hourigan, A. (2009). Teaching Music to Children with Autism: Understandings and Perspectives. Music Educators Journal 96(1), 40-45.

Behavior Problems

Adamek, M., & Darrow, A. (2005). Music in Special Education. Silver Spring, MD: The American Music Therapy Association, Inc.

Darrow, A. (2006).Teaching students with behavior problems. General Music Today, Fall 20 (1) 35-37

Madson, C., & Madsen, C. (1998). Teaching discipline: A positive approach for educational development (4th ed.). Raleigh, NC: Contemporary Publication Company of Raleigh.

Resources

Khetrapal, N. (2009). Why does music therapy help in autism? Empirical Musicology Review, 4(1), 11-18. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1811/36602

Anthony, M. (2012), Music therapy and autistic spectrum disorder. Retrieved from www.examiner.com/article/music-therapy-and-autistic-spectrum-disorder

Big Picture. (2014). Music and autism. http://bigpictureeducation.com/music-and-autism

American Music Therapy Association. (2015). http://www.musictherapy.org/

Vocabulary

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)/Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD): a psychiatric disorder characterized by significant problems of attention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity not appropriate for a person’s age

Autism: a neural development disorder characterized by impaired social interaction and verbal and non-verbal communication. One of three recognized disorders on the Autism Spectrum, which includes Asperger Syndrome and Pervasive Developmental Disorder

disability: a disability, resulting from an impairment, is a restriction or lack of ability to perform an activity in the manner or within the range considered normal for a human being (World Health Organization)

entrainment: the patterning of body processes and movements to the rhythm of music

gender: the constructed roles, expectations, behaviors, attitudes, and activities deemed appropriate for men and women

music therapy: a health profession in which music is used within a therapeutic relationship to address physical, emotional, cognitive, and social needs of individuals

sex: biological and physiological characteristics that define men and women

1 Reprinted with permission. Copyright NAfME, 2012, http://www.nafme.org/strategies-for-students-with-special-needs/

2 Reprinted with Permission from NAfME http://www.nafme.org/success-with-autism-predictability © National Association for Music Education

3 Reprinted with permission from NAfME http://nafme.org/tips-for-teaching-students-with-add-or-adhd/ © MENC: The National Association for Music Education (menc.org)

4 Reprinted with permission from NAfME http://www.nafme.org/teaching-students-with-behavior-problems/ © National Association for Music Education (nafme.org)

5 Reprinted with permission from NAfME http://www.nafme.org/dont-let-physical-disabilities-stop-students/ © National Association for Music Education (nafme.org)

6 Reprinted with permission from NAfME http://nafme.org/interest-areas/guitar-education/music-and-students-with-hearing-loss/ © National Association for Music Education (nafme.org)

7 Reprinted with permission for NAfME http://www.nafme.org/strategize-for-students-with-vision-loss/ © National Association for Music Education (nafme.org)